This thesis is explored by Jussi Parikka, who in his seminal work Insect Media: An Archaeology of Animals and Technology, proposes a radical break from this anthropocentric view. He suggests that technology is not solely a human affair, but rather a distributed processembedded also in the bodies and behaviours of animals. The communicative, constructive, and organisational behaviours of insectsfrom the dances of bees to the tunnels of termitesthus become conceptual tools for rethinking our own notions of media and innovation.

Parikka paves the way for a posthuman reading of technology, demonstrating how even in the 19th century, entomologists and philosophers recognised forms of natural technicality in insects. Spider webs, for instance, were described as communication systemstrue signalling webs capable of transmitting information about the type and weight of trapped prey. The perfectly geometric beehives anticipate modular engineering and algorithmic design. Likewise, the acoustic signals of cetaceans, the vector dances of bees, and the collective architectures of termites form cognitive environments and distributed systems that operate without a centralised commandfollowing the logic of swarm intelligence now present in artificial neural networks and autonomous robots.

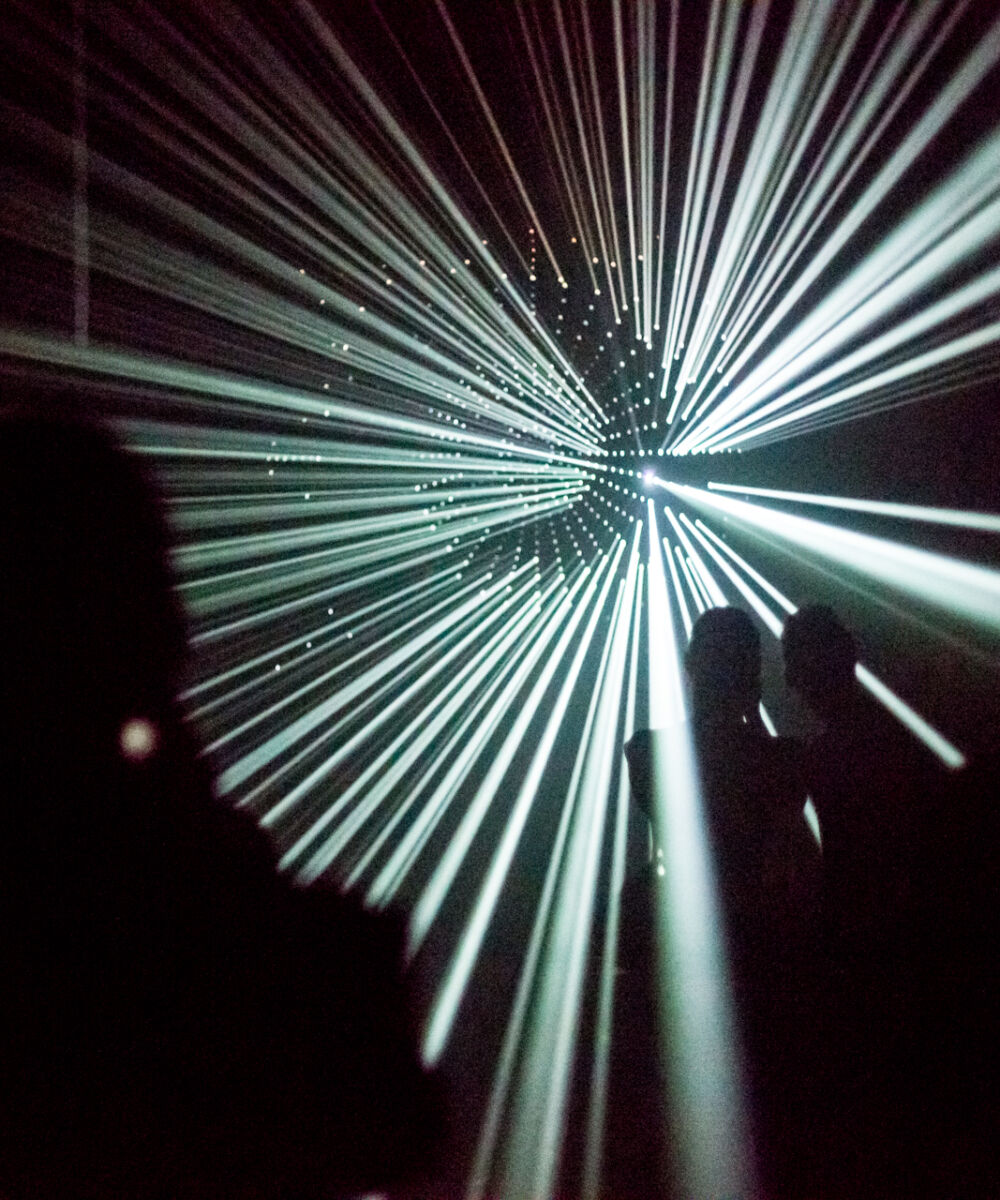

One of the key insights of the text is the use of ethologythe study of animal behaviouras a paradigm for thinking about media. Jakob von Uexküll, an early 20th-century ethologist, argued that every animal lives in an Umwelt, a perceptual world constructed in relation to its own body and sensory abilities. If we extend this logic, we might say that every mediumwhether natural or technologicalcreates its own Umwelt: a reality of signals, flows, and perceptions. In this sense, media are not merely tools, but fields of forcetransindividual environments where perceptions take shape. Technology, then, is not limited to human artefacts: it is what enables orientation, memory, and connection. It is present in nature as the invisible infrastructure of life.

The parallel between insects and digital technologies becomes especially apparent in how the former inspire the design of contemporary computational systems. Parikka references Craig Reynolds boidsdigital simulations that replicate the collective behaviour of flocks and swarms. These algorithms, based on simple rules of proximity and direction, have been used in cinema and military contexts for the automatic coordination of drones. The simplicity of individual agents gives rise to emergent complexitya lesson drawn directly from ants and bees.

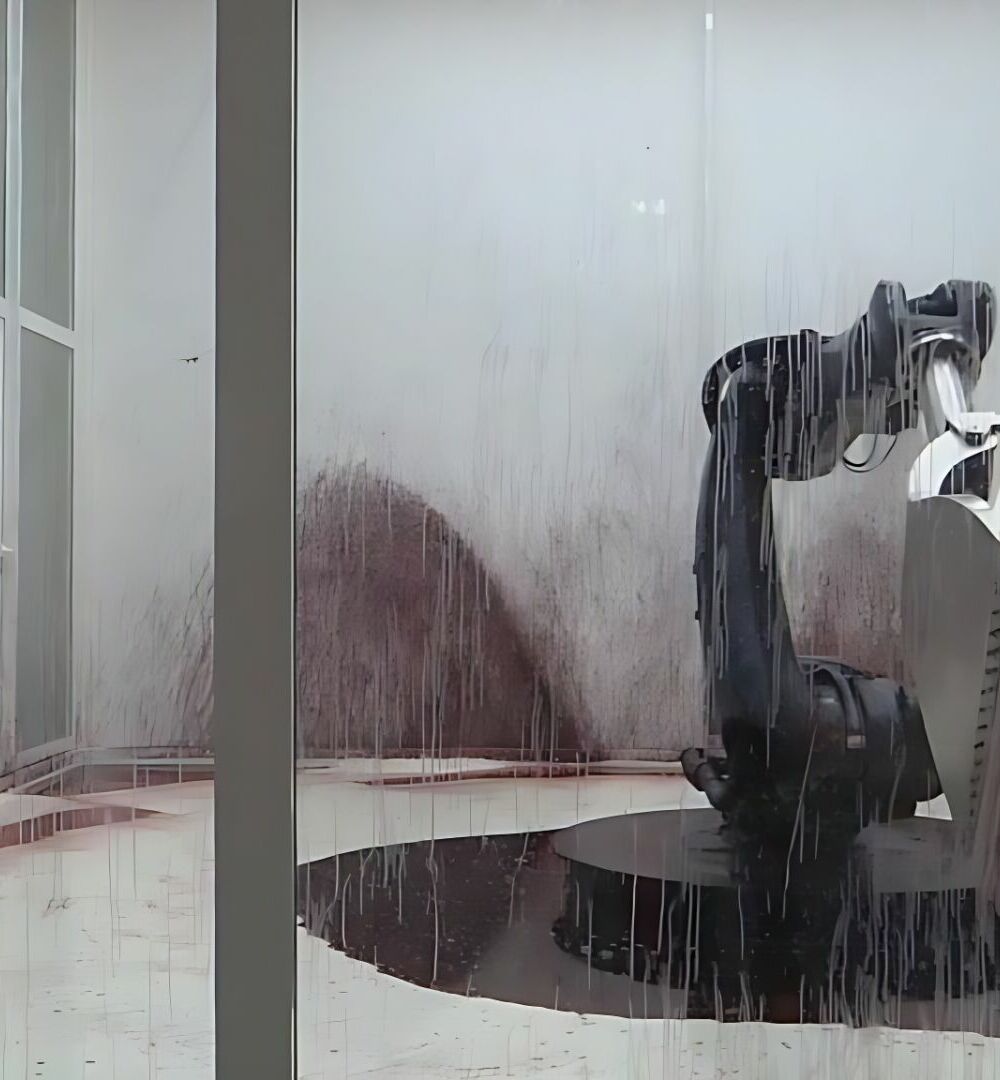

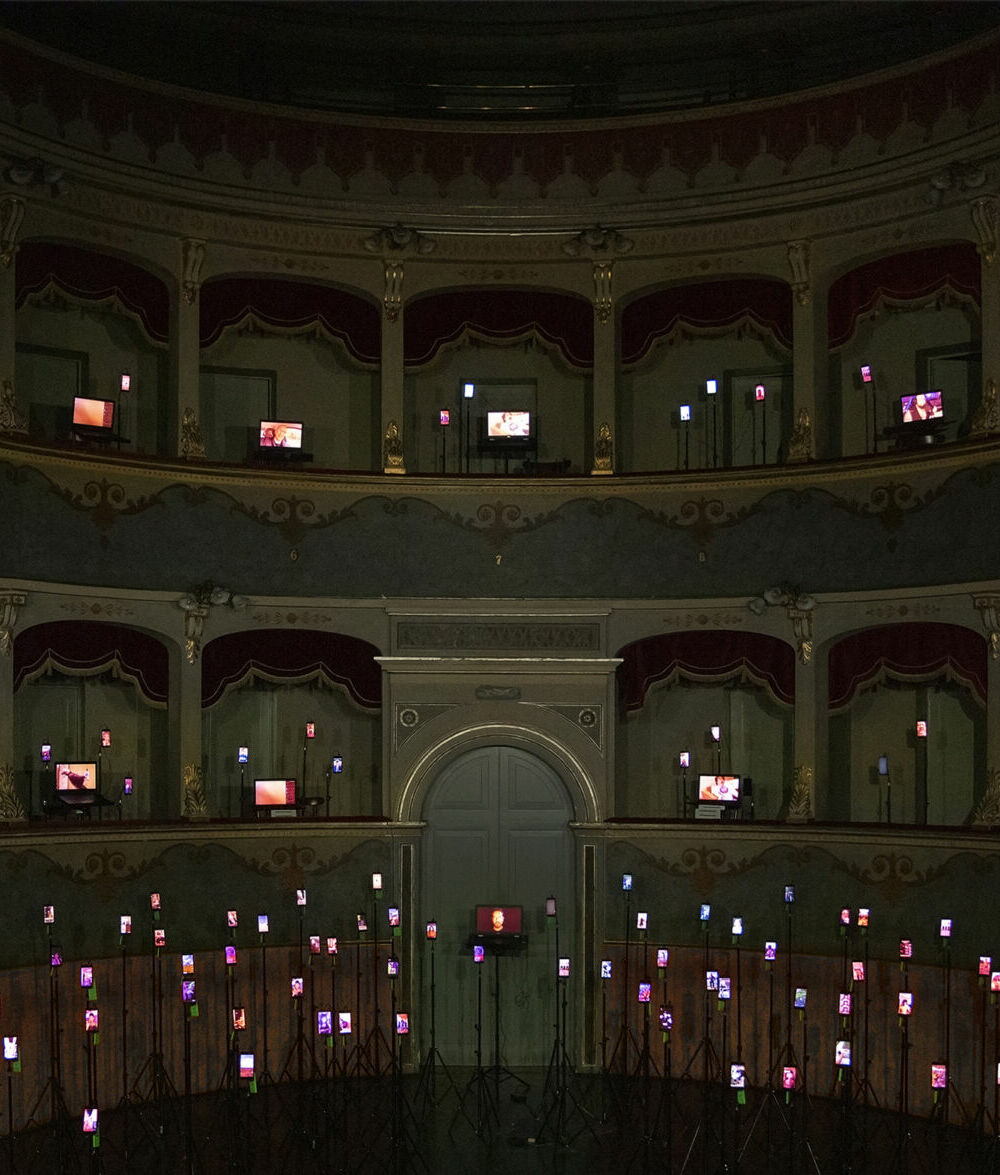

Moreover, numerous contemporary works explicitly incorporate non-human life forms. Consider Garnet Hertzs cockroach-driven robot, or the experimental film Wax, or the Discovery of Television Among the Bees by David Blair, in which the perception of bees becomes a metaphor for a new form of sensory mediation. In bioart, we find emblematic examples such as Timo Kahlens installation Swarm, which transforms a physical space into an immersive sonic environment composed of buzzing bees and vibrationsa kind of art for insects, as Matthew Fuller puts it. And of course, we cannot overlook the webs of Tomás Saraceno.

As Parikka explains, the interest in insects is not merely scientific or artisticit is deeply political. The decentralised structures of swarms have become operative metaphors for asymmetric warfare and biopolitical power. The organisation of termites and bees has been used to rethink governance, surveillance technologies, and algorithmic control. The swarm paradigmas a network without a centreis now central to the functioning of social networks and media theory alike.

This leads to a critical reflection on the nature of power in the contemporary technosphere. If insects teach us a form of distributed intelligence, they also confront us with the risks of total automation, of systems spiralling out of controlan idea already imagined by Norbert Wieners cybernetics or in the figure of the subjectless swarm evoked by Michael Hardt.

It is crucial to stress that this inquiry is not an invitation to exploit nature as a ready-made reservoir of technological solutions. The aim is not to suggest that humans can simply draw upon the natural world to learn its mechanisms and appropriate them, as such an attitude risks reproducing a colonial mindset toward living systems. On the contrary, the ultimate aim of this reflection is to decentre the human, breaking with anthropocentrism and recognising that intelligence and technology are not exclusively human traits. This implies imagining forms of collaboration and co-evolution with other species and natural systems, rather than processes of appropriation or domination.

Ultimately, embracing the perspective of living technologies means acknowledging that mediation and intelligence extend well beyond the humanand that only from this awareness can we envision truly sustainable technological practices.

Is an art historian specialising in art and new technologies and new media aesthetics. Since 2019 she has been collaborating with Artribune (for which she is currently in charge of new media content). In 2020 she founded Chiasmo Magazine, an independent and self-funded Contemporary Art magazine. From 2023 he is web editor for Sky Arte, and from the same year he takes care, for art-frame, of the column New Media, dedicated to digital art.