Videogames, like computing, were born in the U.S. during the Cold War, within industries and universities heavily tied to the needs and funding of the defense sector. The development of the first proto-videogames, such as Spacewar! (Steve Russell, 1962), could be read as a subversive act: a military – or predominantly military – machine, namely the computer of the 1960s and 70s, was turned into a toy. But videogames never truly escaped the orbit of war; on the contrary, commercial software created for entertainment, their development kits (game engines), and the works derived from them have now become a stable part of the military repertoire.

As early as 1980 – 1981, the U.S. Army commissioned videogame company Atari to create a version of its tank simulator Battlezone (1980) for training Bradley vehicle crews in weapons use. In an environment still influenced by counterculture, the conversion encountered some opposition. Later, in 1996, the Marine Corps modified Doom II: Hell on Earth (id Software, 1994) to create Marine Doom, used for training cooperation and communication during operations. The military reuse of commercial videogames, however, became especially significant starting in the second half of the 1990s and even more so after September 11, 2001, with the beginning of the so-called global war on terror by the U.S. The militarization of commercial videogames and the growing production of military-themed games are thus aspects of the broader militarization of civilian life during the war on terror.

In his series Serious Games I – IV (2009 – 2010), director Harun Farocki shows how the U.S. military uses virtual spaces both to prepare troops and to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. Serious Games I: Watson is Down (2010) documents, for example, the Marines’ training in Virtual Battle Space 2 (Bohemia Interactive Simulations, 2007), based on the Real Virtuality 2 engine from the commercial videogame ArmA: Armed Assault (Bohemia Interactive Studios, 505 Games, Atari, 2006), and developed with support from the Australian Defence Force, which had also funded the earlier Virtual Battle Space (2004), based on Real Virtuality 1 from Operation Flashpoint: Cold War Crisis (Bohemia Interactive Studios, Codemasters, 2001). A list published in Randy Nichols’s chapter in Joystick Soldiers: The Politics of Play in Military Video Games (edited by Nina B. Huntemann and Matthew Thomas Payne, Routledge, 2009) cites as many as 17 commercially available videogames used in 2008 as part of U.S. military training.

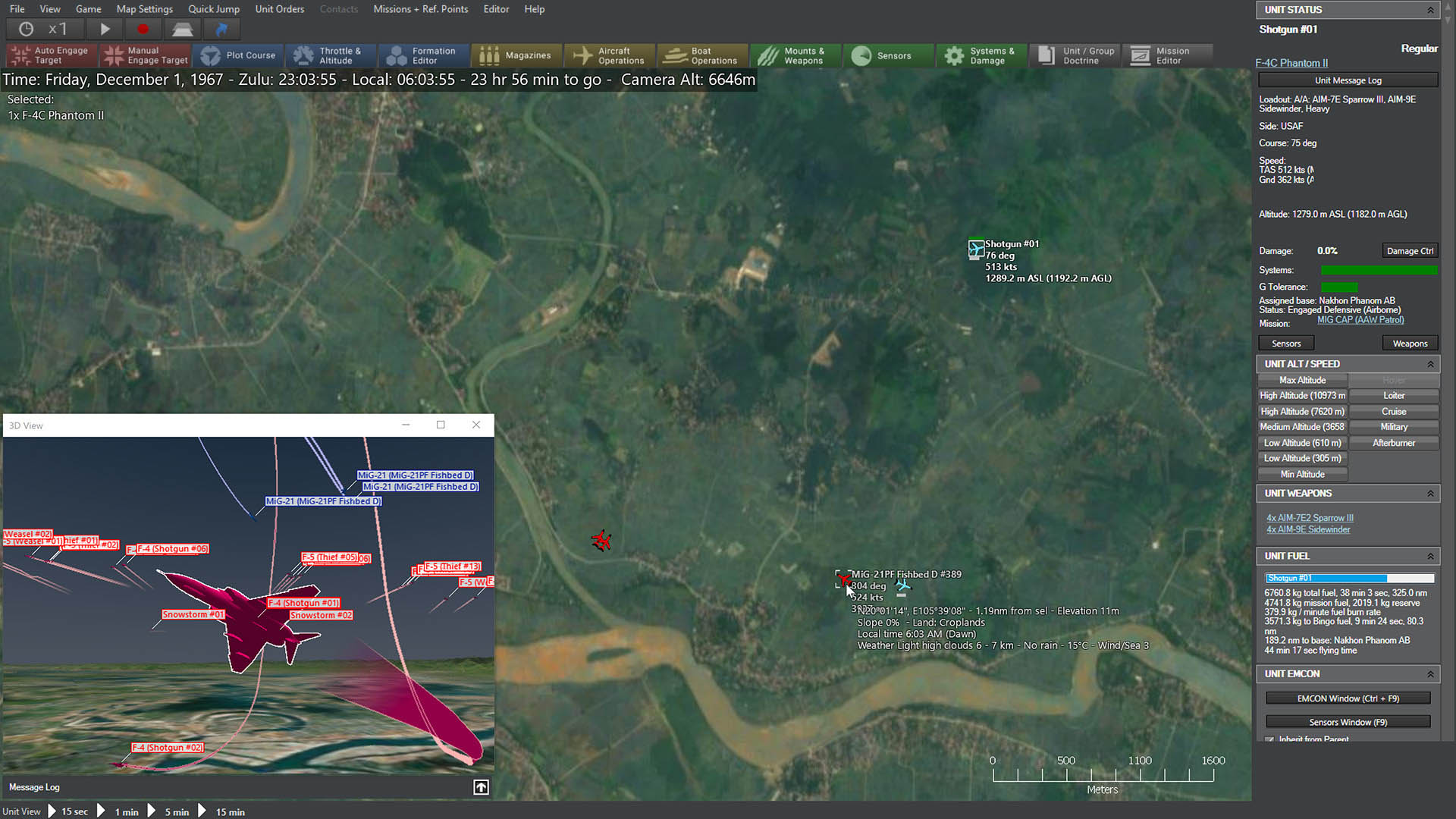

“The gaming world is far ahead of the public sector in terms of technology,” says Marco Minoli, publishing director of Anglo-Italian company Slitherine and winner in 2025 of the Outstanding Individual Contribution award at the Italian Videogame Awards organized by IIDEA, the Italian videogame industry association. Slitherine specializes in strategy games and produces professional versions of its commercial products for the armed forces of various countries. “With just a fraction of the money they’d spend developing this software, they can have one already available, which they can modify (we sell very open versions), or they can ask us to make changes,” Minoli continues. For analysis they offer Command, “a holistic platform that lets you test systems, plan and analyze missions, use large language models to create scenarios, and then have the software play them millions of times with small parameter changes to understand possible outcomes – ” The main U.S. client is the Air Force Research Laboratory, which uses it to plan fuel consumption in the Southeast Pacific. Command is also used for education, meaning training and wargaming. “We organize summits, either joint-force or international, and the software is used to engage with specific scenarios we set up,” explains Minoli. For education at the level of military schools, there is also the tactical simulator Combat Mission.

A different case is America’s Army (2002), a squad-based online first-person shooter developed with a commercially available game engine (Unreal Engine) directly by the U.S. Army itself to reach potential new recruits. As Colonel Casey Wardynski, project director, recounts in an interview also included in Joystick Soldiers, America’s Army was one of the responses to a collapse in enlistments. The goal was to reach a young audience, ages 13 and up, and familiarize them with the Army before they turned 17, the minimum age to enlist. “The game is involved in creating a better-prepared customer,” Wardynski explains. America’s Army is an advergame, a playable advertisement as part of a rebranding operation that brought the Army into popular culture: its success launched a series that continued until 2022.

Videogames can easily become military tools because they are toys open to new interpretations. But precisely as toys, “military games have the potential both to convey an ideology and to have that ideology undermined, even as they provide training only previously available by joining the military” writes Nichols. Indeed, interacting with systems – even if hidden in that black box that is a videogame – can make people aware of how they work, tempting them to test their limits, and to break them.

It was within America’s Army, between 2006 and 2011, that U.S. artist Joseph DeLappe carried out the online performance dead-in-iraq, at once a memorial, a protest, and a warning. DeLappe would enter an online match of the game and, instead of joining the battle, type into the public chat the name, age, branch of service, and date of death of U.S. soldiers killed in the ongoing Iraq invasion. When he wasn’t expelled, his character was inevitably killed, and DeLappe continued typing in front of the corpse of his virtual soldier, which took on a central role in the photographic documentation of the performance and its later reinterpretations (in sculptures and graphite drawings). The digital corpse becomes a substitute for images of dead soldiers and their coffins, censored by the government. “I grew up during the Vietnam war and remember, vividly, the images one would see in popular magazines such as Life and Time – these played no small part in helping cement opposition to this war” DeLappe writes. “The Bush Admin disallowed such, with – embedded’ journalism and strict controls over such images.” The work had a precedent: War Poets Online (beginning in 2002), where DeLappe inserted into the chat of an online military videogame (in its latest version, Verdun by Blackmill Games, 2015) poems written during World War I by British poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. Another project, iraqimemorial.org (no longer online), gathered proposals for memorials dedicated to Iraqi civilian victims – of whom no complete record exists – and culminated in an exhibition in New York in 2011. “I likely previously believed that if Americans could actually see the results of our violence abroad, either that of our soldiers, or its civilian victims, that this might somehow change hearts and minds,” DeLappe concludes. “I was perhaps na – ve in this belief.”

Machinima – films made within videogames – have also often critically addressed the representation of war in the medium. Deviation (Jon Griggs, 2006), the first film of this kind to premiere at a major festival (the Tribeca Film Festival), was shot in Counter-Strike (Valve, Sierra Studios, 2000), a game similar to America’s Army. A virtual soldier becomes aware of his futile cycle of deaths and resurrections, but cannot convince his comrades to abandon combat and orders. Because in war games “desertion cannot be played,” says the voiceover in another machinima, How to Disappear – Deserting Battlefield (2020), in which the collective Total Refusal starts from yet another shooter, Battlefield 5 (Electronic Arts, 2015), to tell the story of desertion and disobedience, and their absence from military videogames. But perhaps the point is that “war cannot be played,” as the voiceover suggests. “By definition, a game is played voluntarily – and for most of the participants, there is nothing voluntary about war in the real world.

Matteo Lupetti writes about art criticism, digital art and video games in publications such as Artribune and Il Manifesto and abroad. He has been on the editorial board of the radical magazine menelique and the artistic direction of the reality narrations festival Cretecon. His first book is – UDO. Guida ai videogiochi nell’Antropocene’ (Nuove Sido, Genoa, 2023), a reinterpretation of the video game medium in the age of climate change and within the new multidisciplinary paths that foreground the non-human and its agency.