Whereas linguistic power was once exercised through explicit prohibitions and recognisable censorship, today it lurks in the invisible infrastructure that regulates communication.

Automatic content moderation does not impose explicit silences, but rather constructs environments in which certain phrases, words, hashtags and names disappear without a trace, pushed to the margins by the very architecture of the network. This is where a new grammar of power is being drawn up, where it is not political banishment but statistical calculation.

This transition is anything but technical; it is political in its most radical form, because it redefines the very conditions of linguistic experience. An algorithm not only decides what violates a specific policy, but also what deserves to be seen, read, monetised. In this twist, language shifts from the realm of expression to that of classification, and with this, the way we imagine freedom, conflict, and the very possibility of speaking also changes.

Traditional censorship operated with the force of clarity. The authorities issued bans or prohibited words (we have seen this done very recently by Donald Trump or, in our own context, through some mysterious school circulars), the rule was as visible as it was brutal, regulating language by defining what could not be said (really). In the digital age, however, the framework has shifted. It is no longer explicit prohibitions that delimit the field of discourse, but invisible processes that filter, downgrade and render imperceptible. Censorship appears and acts as calculation, technical compatibility. Algorithms do not know what it means to prohibit; they translate words into data, analyse them as statistical sequences, and pigeonhole them into categories that determine how they function. In this transition, censorship becomes a problem of computability, where anything that does not fall within the parameters of relevance or security is not explicitly banned, but slips out of the perceptual horizon.

It is here that language, from a field of symbolic conflict, is transformed into classifiable input. This shift marks a profound discontinuity, because while traditional censorship produced visible resistance, and therefore opposition, today regulation appears neutral and almost natural, defining a terrain in which the user does not know whether content does not appear because it has been removed, downgraded or simply buried by the algorithm: what disappears bears no trace of the political gesture that made it invisible. This is how political banning is transformed into computational architecture, and the question of language becomes confused with that of the infrastructure that makes it possible.

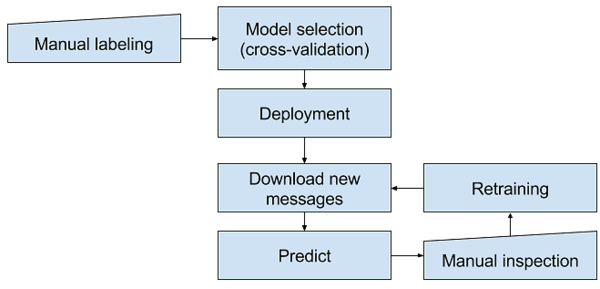

Let’s take a step forward, delving a little deeper into the system. In this context, we are beginning to understand that algorithms do not simply filter content; rather, they rewrite the very conditions of language. Technical and critical literature on content moderation [1] highlights how platforms operate through recurring criteria such as relevance, safety and monetisation. Studies on content ranking [2] show that visibility depends on relevance scoring systems that predict what will generate attention. Classification models segment language into safe or risky categories, treating ambiguity as statistical noise. Guidelines for advertisers (from YouTube to Meta) make it clear that commercial compatibility is an integral part of the process: content remains accessible but is downgraded or demonetised if deemed unsuitable for advertisers (a practical example can be found in Google’s guidelines on content suitable for advertisers for advertisers who are part of the YouTube Partner Programme[3]).

The way in which digital platforms have treated content related to Palestine in recent years provides a privileged observatory of this invisible grammar of power.

In this operational syntax, language is duplicated: on the one hand, human discourse, with its richness and polysemy; on the other, computable discourse, optimised to circulate without friction in the infrastructure, where anything that does not adhere to this grid is not explicitly prohibited, but made imperceptible, pushed to the margins through downgrading, non-recommendation or demonetisation. A policy of visibility that presents itself as neutral technical optimisation, but which in reality acts as a form of discourse governance. This grammar therefore functions by thresholds and confidences where words are not judged to be true or false, lawful or unlawful, but more or less risky, more or less suitable for distribution. What exceeds statistical simplification is not refuted, it simply disappears.

Ranking is where this ontology becomes experience. Far from being a neutral operation, it is a political calculation disguised as optimisation. The algorithm learns from engagement signals and security constraints and reflects them back as discourse order in a feedback loop where past attention determines future attention. Thus, the present is pushed to resemble the past that has already performed, while the new, the minority, and the non-conforming are statistically disadvantaged. Monetisation closes the loop. If a term or topic is associated with risks for advertisers, the infrastructure cools it down preventively. Here, moderation merges with the market, security becomes commercial compatibility, and semantics bends to profiling. In short, this invisible grammar does not say no, it says less likely. It is a power that acts upstream, in the design of thresholds, and downstream, in the management of attention. And this power becomes a political-ontological device: it regulates not only what is said, but what can become effective speech within a calculated attention economy.

The way in which digital platforms have treated content related to Palestine in recent years provides a privileged observatory of this invisible grammar of power. Reports by organisations such as Human Rights Watch [4] have documented the systematic nature with which posts, hashtags and accounts have been obscured, downgraded or suspended. What emerges clearly is that most of these interventions did not arise from explicit policy violations (i.e., incitement to violence, sexually explicit content, or obvious/proven misinformation) but from their incompatibility with the technical protocols and risk criteria applied by moderation algorithms. This is a paradigmatic case because it highlights the gap between stated rules and actual infrastructure.

Meta’s official policies talk about security, transparency and inclusion; in practice, however, the story is quite different, with perfectly legitimate content being pushed below the threshold, hashtags linked to protests or tragedies being cooled by ranking systems, and entire accounts being suspended on the basis of statistical correlations that mistake political activism for incitement to violence. Here, the three axes of invisible grammar find concrete expression. Relevance: pro-Palestinian content is made less visible in timelines and removed from recommendation circuits. Security: the political context is treated as a risk of escalation and therefore filtered preventively. Monetisation: the commercial sensitivity of advertisers acts as an additional lever of penalisation, reducing the circulation of topics perceived as brand unsafe. In this intertwining, the problem is not so much the violation of an explicit rule as the technical and commercial impossibility of accommodating discourse that exceeds the parameters of the platform. What emerges is a dual effect: on the one hand, a drastic reduction in the visibility of Palestinian voices; on the other, the emergence of technical resistance strategies, such as glitched writing, hybrid transliterations and creative use of emojis, which seek to evade automatic reading.

It is not the political statement that is explicitly prohibited, but its linguistic format that is incompatible with the logic of computability. It is in this gap between human discourse and algorithmic discourse that an invisible power lies, which does not directly deny speech, but pushes it out of the space of collective attention.

The Palestinian case shows us that censorship is no longer a question of what is said, but of how it is treated by the technical system that hosts it. It is not the political statement that is explicitly prohibited, but its linguistic format that is incompatible with the logic of computability. It is in this gap between human discourse and algorithmic discourse that an invisible power lies, which does not directly deny the word, but pushes it out of the space of collective attention. The Palestinian case is not an exception, but a symptom. It shows how the technical protocols of platforms become the real sites of language governance. Alexander Galloway [5] has clearly explained the concept of protocols, which are not neutral rules, but control devices that act precisely in their apparent invisibility. Algorithmic moderation is the policy that is directly inscribed in the calculation. Here, the distinction between technique and power dissolves. Talking about model errors or technical failures in moderation risks masking the more radical question: what is language today when it is reduced to computable input

These conventional rules that govern the set of possible behavior patterns within a heterogeneous system are what computer scientists call protocol. Thus, protocol is a technique for achieving voluntary regulation within a contingent environment. [6]

The trajectory we have defined and observed so far does not describe a simple change of tools, but an actual ontological change in which words are no longer just what is spoken, but what can be computed. And this is the heart of the invisible grammar of power, the ability to govern language through thresholds, metrics and protocols that decide in advance its form of existence. Speaking today always means, to some extent, speaking to a machine that decides if and how the word will be distributed.

Faced with this scenario, our criticism cannot be limited to denouncing censorship or demanding greater transparency. We need to develop a critical theory of linguistic computability capable of intercepting and unmasking the power exercised in the infrastructure, seeking to recognise the practices of resistance that emerge at the margins. It is in this interstice between human language and algorithmic language, between word and data, that the possibility of new forms of conflict, imagination and therefore freedom will be played out.

[1] Introduction to Digital Humanism; Chapter On Algorithmic Content Moderation; Erich Prem and Brigitte Krenn; Springer; 2023

[2] Algorithmic content moderation: Technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance; Robert Gorwa, Reuben Binns, Christian Katzenbach; Big Data & Society; 2020

[3] Advertiser-friendly content guidelines

[4] Metas Broken Promises. Systemic Censorship of Palestine Content on Instagram and Facebook

[5] Alexander R. Galloway is a writer and computer programmer who deals with issues related to philosophy, technology and theories of mediation. On the concept of protocol, please refer to the text Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralisation, MIT Press, 2004.

[6] Ibidem

Born in 1992, he writes to decipher the present and the future. Between language, desire and utopias, he explores new visions of the world, seeking alternative and possible spaces of existence. In 2022, he founded a project of thought and dissemination called Fucina.