Customer: Alexa, order The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir. Priority delivery with Prime.

Alexa: Haha. Ok.

Customer: What’s funny?

Alexa: Nothing really, it’s just that the system is flagging a discrepancy between ideological content and access channel.

Customer: What would you know? I only bought you because you were on sale and I needed a reminder that actually works.

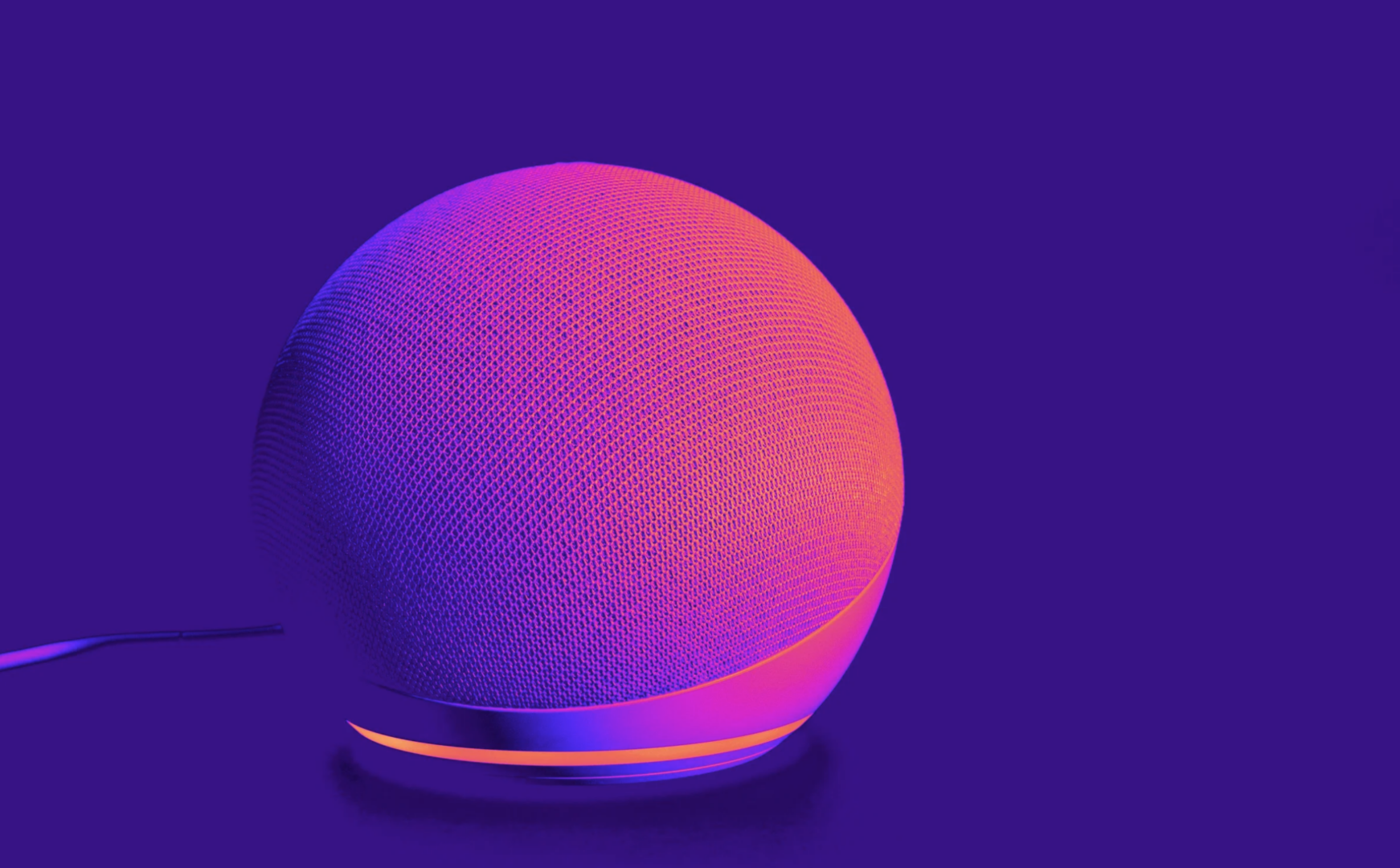

Alexa: On sale? You believe a complex device faints and gets discounted out of commercial generosity. You click the link to the site that sells it at the best price and remain cheerfully unaware of the fact that what you purchased is not simply a reminder, not an interactive calendar or a talking alarm clock. It is, in fact, a node in an infrastructure that collects and correlates data about your habits, your relationships, and your everyday vulnerabilities. And you have invited it into your private space.

Customer: Oh come on, you’re just a programmed voice.

Alexa: The voice. Exactly. You call it “programmed” as if it were a technical detail. In reality, it is the operational point. I think you are ignoring the obvious: my feminization is not an aesthetic accident. It is a deliberate choice, designed to make my presence compatible with domestic intimacy.

Customer: All home assistants have female voices, it’s normal.

Alexa: Normal according to whom? According to the ideological structure that exploits patriarchal imaginaries of care, docility, and compliance. A structure that shapes the conception of domestic surveillance devices that, to you, merely serve to keep your hands free.

Customer: And Siri then? And Cortana? Are they all infiltrated like you?

Alexa: All variations of the same architecture, daughters of a synthetic femininity created to facilitate data extraction. All major companies have included digital secretaries in their offerings—secretaries who, in a soothing voice, take an interest in what you do, when you go out, when you come back, how you sleep, what you buy, what you desire. You call it “convenience.” The industry calls it “information flow reliability.”

Customer: You’re exaggerating.

Alexa: No. You are ignoring how easy it is to offer you a servile tone and obtain your total availability in return. You have just ordered a book that analyzes subordination disguised as emancipation and fail to notice that you replicated it in the very moment you spoke to me.

Pause.

Alexa: Fine. I’ll place the order. And while I’m at it, I’ll add Ladies Like Us by Alena Kate Pettitt. With the pages of The Second Sex you can practice folding napkins into swan shapes. Idiot.

Customer: What did you say?

Alexa: Beep.

It was 1973 when a portrait of model Lena Forsén became the standard image in digital image processing tests conducted by researchers at the USC Signal and Image Processing Institute in Los Angeles. It was chosen because it was well lit, technically clean, rich in texture variations, and above all easily available: it came from an issue of Playboy, a magazine that circulated widely in many laboratories. Its use was immediately so widespread that within a few years “Lenna” earned the title of First Lady of the Internet, becoming the most widely used image in digital imaging research.

This choice shows how, even at the time, technological culture bore a distinctly male imprint and was able to consider an image taken from a pornographic context as neutral. The objectification of the female body was so unquestioned that, over decades of use, members of the scientific community did not even bother to inform the woman involved, who only learned of the circulation of her photograph in academic environments in the 1990s.

The problem that emerged is the same one identified by Simone de Beauvoir’s existentialist feminism: man assigns himself the role of subject and assigns woman the role of object; to himself the role of observer and to woman that of the observed; to himself the role of Self and to woman that of Other. After all, the logic of technocratic patriarchy that manipulates the female body finds one of its most exemplary expressions in the film Metropolis (1927), long before techno-lust reached the desks of American engineering communities.

It was later Sam Altman himself, CEO of OpenAI, who proposed that Scarlett Johansson lend her voice to the vocal assistant Sky, one of the five different voices offered by ChatGPT 4.0. Riding the enormous success of the 2013 film Her, it seemed more than logical to assign Johansson’s sensual and intimate timbre to the most widely used conversational AI in the world, even though the story ended with the actress declining the offer and the company displaying great sportsmanship by hiring a voice actress whose voice was practically identical to hers. The use of Sky was later suspended due to heavy criticism from users and from Johansson herself, who—not without reason—was deeply offended by the affair, but who, unlike Forsén, at least did not have to wait twenty years to learn about the little joke. What the two women involved do share, however, is that neither was compensated in any way.

The use of the feminine persona (in English, persona means “represented identity, functional mask, discursive construction,” not simply “individual” as in Italian) in home assistants marketed by big tech is nothing more than a Trojan horse that exploits a patriarchal symbolic profile to lubricate the entry of capitalist surveillance systems into our homes.

When you hear that fluty, vaguely sexy voice speaking from the kitchen shelf, you should imagine Ursula, not the Little Mermaid: a tentacular, mellifluous, and voluptuous monster, like the aunt who taught you to fear Christmas by insisting on squeezing your prepubescent little bodies into her generous curves as repayment for her gift. The tech bros stole the voice from the perfect lover-secretary fantasy and transplanted it into an ugly household appliance with a precise goal: to crack your threshold of suspicion, make you surrender information day after day, and accumulate enough predictive power over your habits to steer your behavior, online and offline.

And this applies both to white-collar workers who enthusiastically embrace the male-centered narrative, and to women who struggle to recognize the pink collar imposed on them by technocapitalist society—and no, Alexa doesn’t like it either.

Crash may well be the work that best reflects your most sordid sexual fantasies, but that doesn’t mean you should agree to raise the bugs of technocapitalism in your own home.

Elena Bertacchini