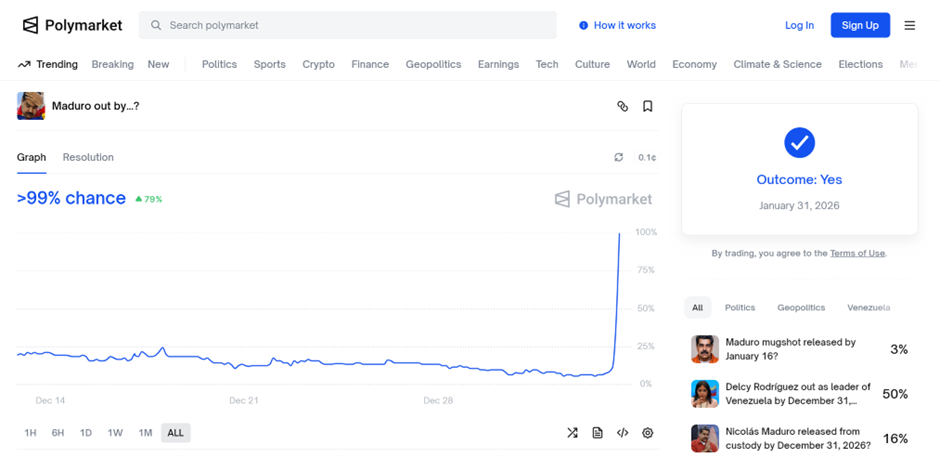

A few hours before Trump gave the order to attack Venezuela, an anonymous bettor had placed more than $20,000 on Nicolás Maduro’s downfall on Polymarket — one of the main sites that are part of the blockchain and cryptocurrency-based prediction market.

The same account, as the Wall Street Journal reconstructed in detail, had bet another $14,000 in the preceding days on a U.S. invasion of the country and on Maduro’s removal — two outcomes that, despite the geopolitical tensions of the previous months, appeared fairly unlikely.

Needless to say, the value of the odds skyrocketed as soon as the first news of the U.S. military operation leaked on January 3rd, allowing the bettor to make over $400,000. What made the situation even more suspicious was that the account in question had been created at the end of December and had only bet on Venezuela. There are two possibilities: either this bettor was incredibly lucky and prescient; or they had access to confidential information that the Trump administration and military leadership had kept under wraps. If that were the case, we would be facing something unprecedented: a case of insider trading on epochal geopolitical events.

Polymarket has not taken a firm stance on the nature of the bet, but nevertheless refused to pay out, arguing that the operation does not constitute a full-scale military invasion. In an official statement — more like something from a geopolitics magazine than from a betting site — it read that “President Trump’s statement that the United States will ‘run’ Venezuela, while referring to ongoing talks with the Venezuelan government, is not in itself sufficient to qualify the mission aimed at capturing Maduro as an invasion.” This explanation infuriated many bettors, who accused Polymarket of changing the rules mid-game and of lacking the expertise necessary to make decisions of this importance. “That a military incursion, the kidnapping and conquest of a country are not classified as an invasion is simply absurd,” one user wrote.

As bizarre or unusual as it may seem, so-called prediction markets are having an increasingly significant impact on U.S. and global politics. Polymarket, precisely, is the most glaring example. Founded in June 2020 by then 22-year-old Shayne Coplan, the platform is a cross between a betting site and a financial trading site.

Here’s how it works: users buy and sell smart contracts (i.e., digital contracts on the blockchain) based on future events of any kind — economic, sports, or political. The price of each contract reflects the probability assigned to that outcome. If the predictions prove accurate, the difference between the price paid and the final value of the contract is settled in cryptocurrency.

Although similar sites already existed, Coplan’s startup has gained traction thanks to its ease of use, a very low minimum entry for bets, and certain historical contingencies — including the gambling boom during the pandemic, the loosing of some regulatory restrictions, and the 2024 U.S. presidential election.

It was during that period, in fact, that the platform became known to the public. On Polymarket, bettors favored Donald Trump over the Democratic challenger Kamala Harris, contrary to what traditional polls were showing.

After correctly predicting the election outcome — which, in fairness, had always been fairly close — the platform gained a reputation as a “real-time thermometer” of politics, more accurate and reliable than the media and polling institutes.

For academic Jason Wingard, prediction markets are a barometer of public opinion more objective than polls. In Forbes, he wrote that “polls measure what people say, while bets measure what people believe. When honesty has a cost, people are simply more honest.”

Independent studies on the actual reliability of prediction platforms are still few, and some highlight several structural problems — above all, how easily they can be manipulated. Moreover, from a regulatory standpoint, Polymarket operates in a zone that is a euphemism to call gray. Some countries consider it a financial trading company, others (like Italy) see it as a gambling site.

In the United States its status is rather convoluted and opaque. In 2022 the company blocked access to U.S. users after paying a $1.4 million fine to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC, the federal authority that regulates derivatives markets) for failing to properly register.

Despite this, it was still possible to access and place bets with a simple VPN (virtual private network). For this reason, toward the end of Joe Biden’s term, the New York federal prosecutor’s office and the CFTC opened two investigations. Coplan’s home was even raided by the FBI. Both investigations were closed shortly after Trump’s return to the White House, but I’ll return to this later. In December 2025 Polymarket officially resumed operations in the United States, albeit by invitation and with limitations on some types of bets.

The other major problem afflicting the platform, as shown by the Venezuela case, is insider trading.

While rival sites like Kalshi explicitly prohibit it (enforcement is not that easy either), Polymarket imposes no limits. On the contrary: Coplan encourages insider trading. “The cool thing [about the platform] is that it creates a financial incentive for those who reveal information to the market,” he said at an event.

He’s not the only one who thinks this way. Economist Robin Hanson told Decrypt in an interview that “if the purpose of prediction markets is to get accurate information on prices, then it’s absolutely necessary that those with privileged information be allowed to operate, even if this discourages others from betting.”

In a way, Polymarket has normalized and democratized the abuse of privileged information. If not long ago it was a sophisticated crime à la Gordon Gekko, now it is a lucrative financial tool theoretically open to anyone.

Last December, for example, a platform user earned one million dollars in just 24 hours by perfectly predicting Google Search’s annual results — information that only a Google employee could have known exactly.

Two months earlier, in October 2025, the platform effectively anticipated the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to María Corina Machado. A few hours before the official announcement, her chances of winning suspiciously rose, as if someone already knew everything. Kristian Berg Harpviken, director of the Nobel Institute, stated “we were the victim of a criminal who wants to profit from our information.”

The point is that this information, unlike classic insider trading, is not limited to finance or stock markets; it concerns, well, all human knowledge. After all, as Kalshi co-founder Tarek Mansour explained at an event, “the long-term vision is to financialize everything and turn differences of opinion into a tradable good.”

And this brings us to the last big problem of prediction platforms, the one that attracts the most criticism and concern: the total absence of ethical and moral scruples.

On Polymarket and similar sites you can bet on whether Zelensky will wear a particular outfit during an official meeting; whether a specific area will be hit by a natural disaster; whether a fire in a given zone will be extinguished; on which day and hour the Pope will die; how many posts Elon Musk will make on X; and so on.

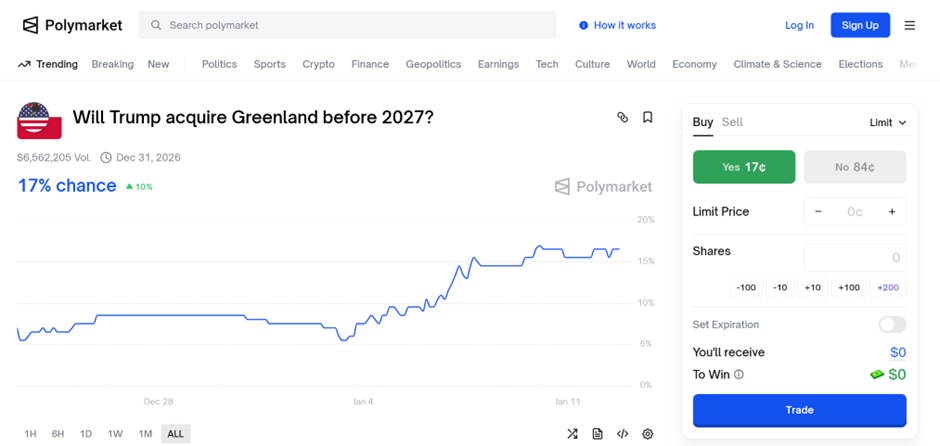

And you can also bet on elections, political decisions, and even wars. You can indeed bet money on the use of nuclear weapons by Vladimir Putin, on the movements of the front in Ukraine (complete with doctored maps showing nonexistent Russian advances), on genocide in the Gaza Strip, on the fall of the Ayatollah regime in Iran, on when Trump will annex Greenland, or on World War III.

The act of betting anonymously on political current affairs has enormous implications, and can truly redefine the concept of “conflict of interest” by pushing it into uncharted territory.

A member of Congress, for example, can behave like a soccer player who throws a match — perhaps helping to pass or sink a law they’ve bet on. And a military officer can do the same by placing money on the outcome of a secret military operation they are privy to.

In other words: with Polymarket you are financially incentivized to rig politics.

In an attempt to avert this scenario, Democratic Congressman Ritchie Torres has recently filed a bill to ban public officials and federal employees in possession of “nonpublic, material information” from operating in prediction markets.

But for the Trump administration, betting platforms shouldn’t be regulated for a very simple reason: they are an excellent source of personal profit for the president, his family, and Silicon Valley’s broligarchs.

It’s no coincidence that both Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in Polymarket and Kalshi. And it’s no coincidence that Trump’s eldest son, Donald Trump Jr., who is also a strategic consultant for both sites, has done so.

Since returning to the White House, as the New York Times detailed in a long report, Trump and his family “have embarked on an unprecedented campaign of enrichment in contemporary American history.” Cryptocurrency-related activities are currently the most profitable for the Trump Organization, and they are a direct consequence of the policies promoted by his administration.

The president — who until a few years ago was a fierce critic of the sector — has dismantled the restrictions introduced by his predecessor, shelved federal agency investigations (including the one involving Polymarket), launched a memecoin, and collected multimillion-dollar funding from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates through the World Liberty Financial stablecoin, the company run by his children and special envoy Steve Witkoff.

This blending of public affairs and private interests is so blatant and brazen that it makes the glory days of Berlusconi pale. Trump himself, after all, openly boasts of being in a conflict of interest. “THIS IS A GREAT TIME TO GET RICH, LIKE NEVER BEFORE,” he wrote a few months ago on Truth Social in his characteristic shouting style.

And indeed, the rise of prediction markets is truly emblematic of the Trump era. An era in which gambling on wars, disasters, and more generally on human suffering is not reprehensible, but simply the new normal.

Leonardo Bianchi