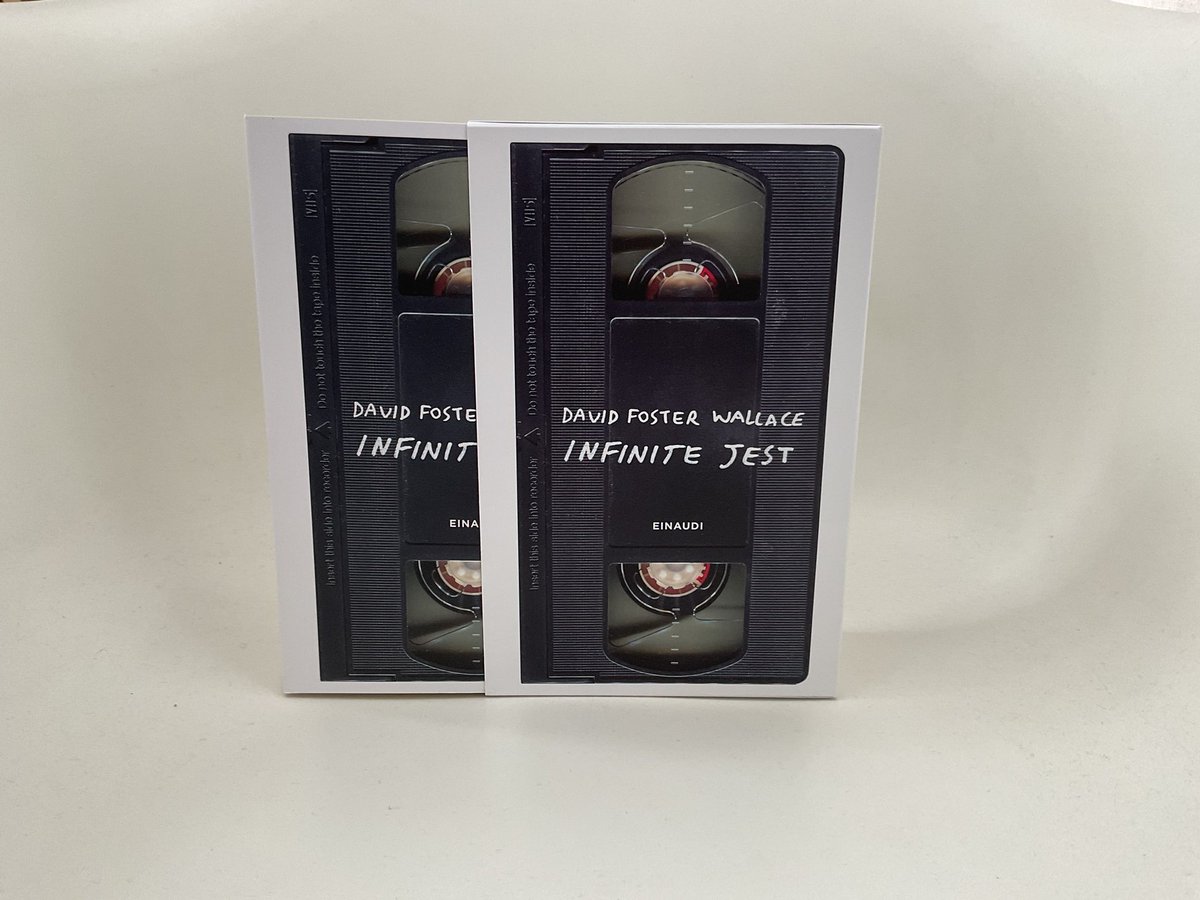

Today Infinite Jest, the most famous novel by David Foster Wallace, turned thirty. To mark the occasion, Einaudi has published a new Italian edition, carefully curated and visually powerful, almost as if to definitively seal the novel’s passage from cult object to contemporary classic. Even today, Wallace’s work proves to be one that, earlier than many others, grasped the mental shape of our era.

It is difficult to say when a novel can be defined as a “cult” work. It does not happen as it does with a film or a band, where the label emerges from a combination of noisy minorities and distracted majorities who, in unison, become aware of a phenomenon that satisfies everyone’s tastes. With Infinite Jest something stranger happened: the cult was born from a work of fiction that was, in part, conceived as disturbing.

Reading it is an act disproportionate to the immediate benefits. A thousand-plus pages, footnotes that multiply almost by mitosis, plots that branch out and then disappear, characters that seem to come from different novels. And yet the book has built a community of readers who do not merely love it: they move through it and talk about it as one does with world-building works, for example The Lord of the Rings.

Wallace’s prose is one of the reasons for this devotion. Not only because it is beautiful in the academic sense of the word, but because it is mobile, restless, capable of shifting from street slang to technical jargon, from drugs to metaphysics, from comedy to drama. All this while continually changing register, tone, rhythm, and point of view. Few novels of the late twentieth century and the early 2000s have produced such a persistent aura without turning into relics.

Telling the plot of Infinite Jest to someone who has not read it is a limited exercise, like summarizing a city with a postcard. There is an elite tennis school, the Enfield Tennis Academy, where prodigious adolescents learn to handle pressures that no one should have to know. There is a recovery community for drug addicts and alcoholics, Ennet House, where desperate residents try to survive their own addictions. There is a group of wheelchair-bound Canadian terrorists (Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents) and there are American government agents who want to stop them. Everyone is hunting for a mysterious video cartridge titled Infinite Jest, precisely: a film so pleasurable that it renders whoever watches it incapable of doing anything else until they waste away. An entertainment so perfect that it becomes lethal.

Around these nuclei revolve dozens of characters: Hal Incandenza, a kind of tennis and vocabulary prodigy; Don Gately, a former addict and burglar, with an almost Dostoevskian moral sense; James Incandenza, Hal’s father and filmmaker, inventor of the “entertainment” that gives the novel its title; and a crowd of Dickensian secondary figures, who always seem on the verge of becoming protagonists.

But the true plot of Infinite Jest is not a story in the classical sense, because Wallace had a radical idea: if the problem of modernity is infinite entertainment, then a novel that wants to speak seriously about this problem cannot itself be easy entertainment.

Infinite Jest is constructed as an anti-spectacle. The footnotes interrupt the narration at the least opportune moment. The chronology is fragmented. Crucial information arrives late, or too early, or never (the ending, for example, is not so much anticlimactic as a-climactic: it lies outside the novel itself, inferred from the way events accumulate). The reader is forced to work, to remember, to go back, to give up the illusion that every story must offer immediate pleasure. Not by chance, its original title was A Failed Entertainment.

The book works, it is beautiful to read, but it refuses the implicit pact between cultural product and consumer. It does not promise continuous gratification.

In those years Wallace was developing one of his clearest intuitions: the effects on human interiority of “spectation” (a necessary neologism, because in Italian there is no equivalent that carries the nuances of the English word “spectation”). A form of existence in which the subject defines themselves primarily as a spectator, for whom being in the world means watching something. Preferably without interruptions. Preferably without silence. Does it sound a little familiar?

Wallace had understood that television had become a true model of experience. It did not merely offer content; it taught a way of occupying time. And that way consisted in reducing every interval, every pause, every moment not filled with images to a kind of error.

Wallace’s lethal film, the work so pleasurable that it annihilates the will of whoever watches it, goes beyond a narrative device. It is a metaphor that today appears almost naïve in its precision, because we have gone beyond the author’s imagination. We live in a continuous flow of micro-entertainments: reels, feeds, notifications, videos of a few seconds, algorithms that anticipate our desires before we even formulate them. Wallace did not see the age of infinite scrolling, but he had intuited its logic thirty years ago.

Think about it, seriously: how free do you consider yourselves today in your need to be entertained? Is it really your choice? And is it possible to consider the lack of stimuli as a form of discomfort?

Infinite Jest tells this mechanism without moralism. It does so with the awareness that the need for entertainment arises from an authentic wound. We want to be distracted because being present and aware, most of the time, is painful. A pain that often hides in boredom.

Today the adjective “boring” has become almost a social condemnation. It is one of the most degrading characteristics we can attribute to an experience or a person.

Before taking his own life in 2008, Wallace had for years been working on The Pale King (published posthumously and unfinished in 2011), a novel devoted to the experience of empty time and tedium. A book that tried to transform boredom into narrative material, as if it were a resource to explore, not a flaw to eliminate. In this sense, Infinite Jest was the first step toward an exercise in resistance to easy remedies for boredom, among which irony.One of Wallace’s most surprising qualities was also his ability to make people laugh while speaking about the most terrible things. Infinite Jest is full of funny scenes, but that comic quality is not a simple ornament. His irony does not serve to protect himself from reality, but to make it bearable. And it is a kind of condemnation: Wallace harbored a deep suspicion toward irony, especially when it became a permanent posture, an emotional shortcut disguised as intelligence. He argued that postmodern irony, after freeing American literature from moralism and rhetoric, risked turning into a cage: a perfect tool for avoiding involvement, for not exposing oneself, for not taking anything seriously, not even pain. In Infinite Jest irony is everywhere, but it is shown as a fragile resource, a defensive language that works only up to a certain point.

Beyond that threshold remains the need to say something sincere, without safeguards, without detachment. That is where Wallace places the novel’s true stakes: the possibility—ever rarer—of speaking seriously in a world that has learned to laugh at everything, and to distract itself even before it understands what it is looking at.

Reading Infinite Jest today means realizing that many of our obsessions were already there, in embryonic form. The fear of silence, the transformation of pleasure into addiction, the difficulty of being alone with one’s own thoughts.

Wallace sensed that pleasure, when it becomes an uninterrupted flow, ceases to be an event and turns into a permanent condition. In that condition desire loses its contours, time flattens out, experience becomes indistinct. There is no longer anticipation, no longer distance, no longer the margin necessary for something to truly happen.

Infinite Jest tells precisely of this vanishing space: the space between an impulse and its satisfaction, between a question and its answer, between an individual and what entertains them. It is a novel built to restore friction to experience, to remind us that consciousness is not a continuous stream of stimuli, but a rough terrain, full of interruptions, detours, and shadowy zones.

Reread today, the book appears less like a prophecy and more like a radiograph. Wallace was observing a world that was learning to find every form of emptiness unbearable, and he tried to turn that very emptiness into narrative material. The effort required to read Infinite Jest, its irregular structure, its resistance to rapid consumption, are part of the same gesture: forcing the reader to stop, to get lost, to remain.

Perhaps this is why, after thirty years, the novel still feels so close to us. Not because it precisely describes our present, but because it lays bare a tension we have never resolved: the need to be entertained and the desire—harder to admit—for something that cannot be consumed.

Niccolò Carradori