A critical and philosophical look at artificial intelligence and its influence on society, culture and art. La Rivoluzione Algoritmica aims to explore the role of AI as a tool or co-creator, questioning its limits and potential in the transformation of cognitive and expressive processes.

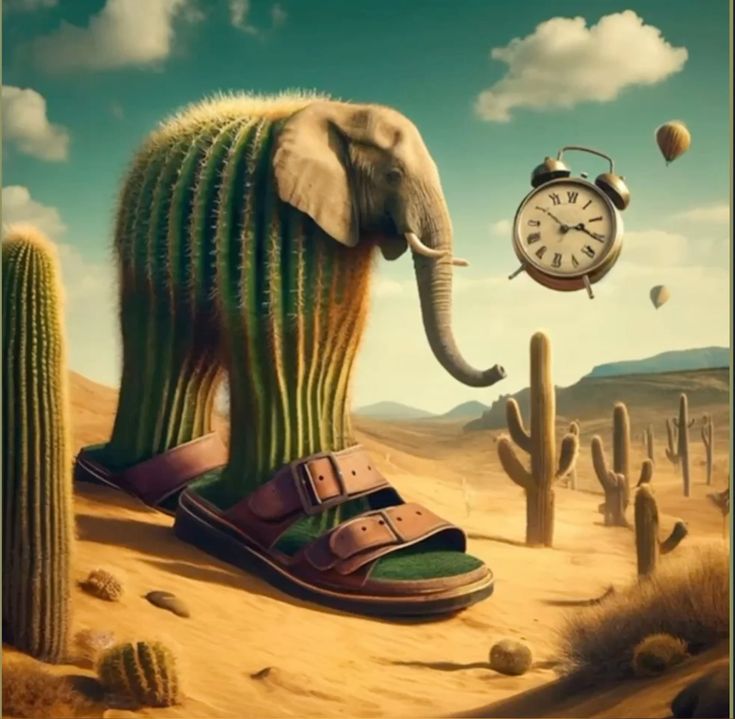

Within a few weeks, names like “Tralalero Tralala” or “Brr Brr Patapim” flood global feeds, spawning thousands of variations. As with all memetic exchanges, the individual author fades into the background, giving way to a fluid collective in which digital tools—image generators, synthetic voices, recommendation algorithms—don’t just support the creative act but become integral to it. TikTok and Instagram are not merely stages for consumption, but co-production arenas, where the boundaries between viewer and creator are constantly renegotiated.

These phenomena are perfect illustrations of Vlad Petre Gl?veanu’s theory of distributed creativity, a revision of the usual concept of creativity that shifts the focus from the isolated genius to the ecology of relationships that make every inventive act possible. At the center is not the “author” but the “action”—a gesture that takes shape at the intersection of different actors, artifacts, audiences, affordances, and timeframes. The actors bring with them experiences, motivations, and knowledge, but only become creative when they interact and trade roles of guidance and listening. Artifacts—whether tools, materials, or algorithms—are not mere supports, but nodes that condense past ideas and open doors to future transformations. The audience is not a passive spectator, but interprets, evaluates, shares, and re-launches content, constantly updating its meaning. Affordances—the constraints and possibilities offered by the cultural and technological environment—guide imagination by providing paths that creativity can either follow or circumvent.

These five poles operate along the three nuanced axes that underpin the creative dynamic. Sociality: every insight is born through interaction, finds confirmation or correction in others’ perspectives, and is nourished by a potentially infinite dialogue. The material-semiotic dimension: tools, languages, and signs not only mediate action but shape its boundaries, often turning limits into springboards. Temporality: every creative outcome builds on previous traces, is reinterpreted, generates variations, and in turn becomes a resource for further inventions. From this perspective, innovation is a constant tension—a fabric that thickens and tears only to recompose itself elsewhere, keeping the continuity between memory and novelty alive. Gl?veanu invites us to read creativity as a fluid, historical, and collective process, where what matters is not the spark of the individual but the web of material, symbolic, and cultural dependencies that make every idea shareable, transformable, and fertile.

If the memetic mechanism seems born from the algorithm, its DNA is in fact ancient and cross-temporal. On the other hand, the Italian brainrot may appear to be a digitally native phenomenon, but it has roots in practices that 17th-century printers would have recognized at first glance. In London, Antwerp, or Venice, print shops created engravings that were reused endlessly: the image of the so-called “how-de-do man” with an outstretched arm in greeting, or of two galleons in battle, migrated from an adventure pamphlet to a love ballad, from a crime flyer to a moralistic tract. Each reuse placed the image in a new context, enriching it with meaning; Katie Sisneros referred to these as “early-modern memes,” describing this constant recycling that turned an engraving into a shared symbol, ready to be reignited with each reprint.

The catalogues of the English Broadside Ballad Archive show hundreds of “promiscuous” printing blocks, passed from press to press over decades until they became unrecognizable from wear. That chain of reuse functioned thanks to a set of constraints (the cost of wood, the rush to market) and an ecosystem of actors that closely reflects Gl?veanu’s theory of distributed creativity. The woodblock was the artifact; the action was the composition of the sheet, as well as the performance of the text; the audience were the passersby who listened, purchased, cut out; the affordances were cheap paper, the absence of copyright, the mobility of street vendors, and the printing press.

The result was a collective mind in which no one truly owned the image, but everyone recognized and adapted it for new purposes—just like today, anyone can take “Brr Brr Patapim,” change the animal or the rhyme, and relaunch the meme into the feed. If in the 17th century the image physically moved from one press to another, today it travels as the output of an AI generator, yet the mechanism remains identical: an idea spreads because someone reads it, interprets it, transforms it, and reintroduces it into the stream. The materials change—wood, paper, pixels, neural networks—but the dynamic of competitive cooperation described by Gl?veanu remains: actors and audience swap roles, artifacts retain traces of previous uses, technologies open and close paths.

Behind the bomber crocodile that pops up on TikTok, we can glimpse the ghost of the “walking-stick man” printed on a broadsheet in 1670. Both live not in the mind of a solitary genius, but in the network of people, images, and repetitions that give birth to them, let them die, and bring them back again.

Francesco D’Isa, trained as a philosopher and digital artist, has exhibited his works internationally in galleries and contemporary art centers. He debuted with the graphic novel I. (Nottetempo, 2011) and has since published essays and novels with renowned publishers such as Hoepli, effequ, Tunué, and Newton Compton. His notable works include the novel La Stanza di Therese (Tunué, 2017) and the philosophical essay L’assurda evidenza (Edizioni Tlon, 2022). Most recently, he released the graphic novel “Sunyata” with Eris Edizioni in 2023. Francesco serves as the editorial director for the cultural magazine L’Indiscreto and contributes writings and illustrations to various magazines, both in Italy and abroad. He teaches Philosophy at the Lorenzo de’ Medici Institute (Florence) and Illustration and Contemporary Plastic Techniques at LABA (Brescia).