In the video game Blippo+ by the musical group YACHT (Jona Bechtolt, Claire L. Evans, and Rob Kieswetter) and Panic, we play while watching television. It’s not today’s television made of platforms, streaming, and on-demand programs: the TV in Blippo+ instead recalls traditional, linear television – a few channels, fixed programming, broadcasting regardless of our presence. In fact, it specifically evokes late-1980s and early-1990s shows. But everything feels a little stranger. That’s because Blippo+ is (in the fiction) an extraterrestrial television network: its signal reaches us from the distant planet Blip through a distortion called “the Bend.” And it’s also strange because Blippo+ (outside of the fiction) was created by involving, for a year, over 100 people from Los Angeles’s underground art scene and filming with real analog cameras at Jennifer Juniper Stratford’s Telefantasy Studios.

Linear TV is special for its ability to create “shared experiences,” Bechtolt and Evans tell us during a video call. Evans is also a technology journalist and the author of Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (Penguin Putnam, 2018). “It’s about everyone seeing something together, experiencing something together, and then being able to discuss it,” Bechtolt explains. “In the streaming era we have access to infinite amounts of stuff both on social media and on television,” Evans adds. “You binge entire seasons. Whereas in older television there’s beginning, middle, and end. There’s this sort of really perfect little package with the title and the theme song and everything fits in a nice little shape. And that’s such an interesting opportunity to play with that.”

Blippo+ was initially released in a version programmed by Dustin Mierau for Playdate, the small handheld console by Panic characterized by a crank and a 1-bit screen: its images consist only of black or white pixels. Dithering techniques – patterns of black dots of varying density – are used to simulate shades of gray. Games for Playdate are distributed digitally through a dedicated platform, but unlike companies like Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft, Panic has not imposed strict control over what gets released for its device. In fact, it made the development tools freely available, and we can load any games we want onto the console by connecting it via cable to a computer or transferring them online. Some games are also published on Playdate as part of “seasons.” The first season comes with the console purchase, featuring 24 games released over 12 weeks. Blippo+, on the other hand, is part of the second season – available for purchase from May 2025 – which includes 12 additional games released over 6 weeks.

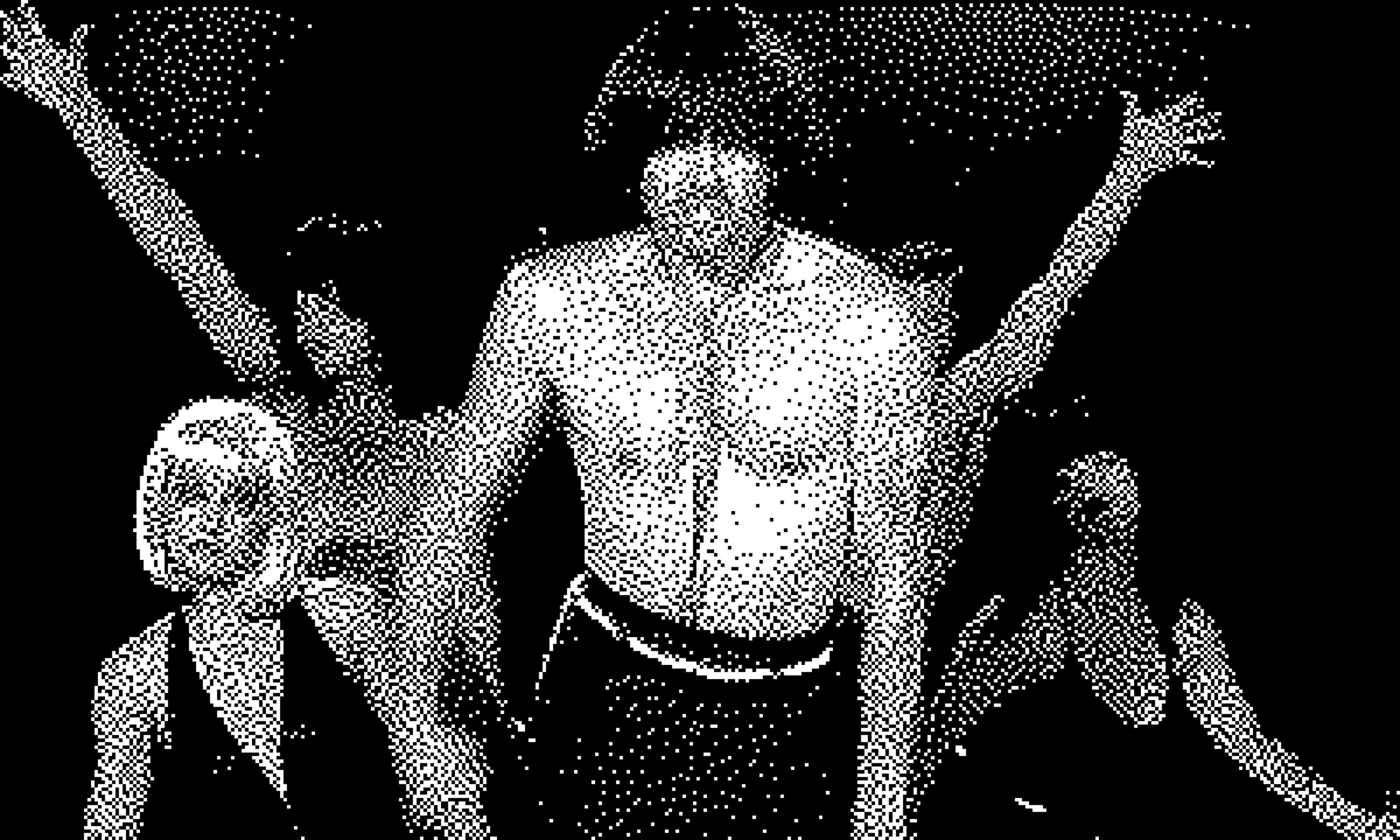

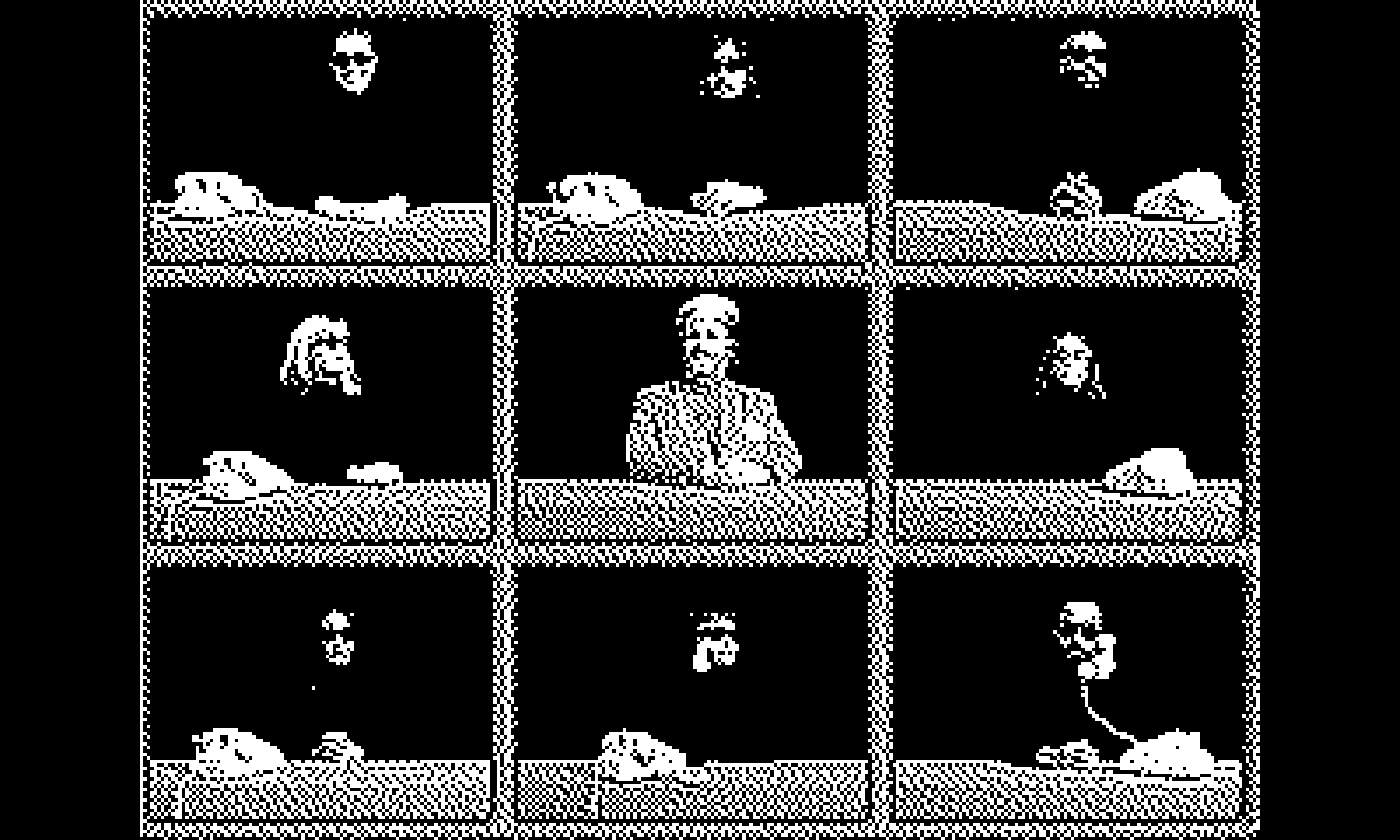

The interface of Blippo+ presents itself as an electronic program guide for channels that cyclically repeat their schedules. Its programming consists of very short shows, tributes to different television genres – from weather forecasts to talk shows, from news broadcasts to “kids’ TV,” from science infotainment to cooking shows (the costumes, designed by Kiki Stash, are consistently remarkable). Every week Blippo+ is updated with a new schedule that replaces the previous one, and after each complete broadcast cycle – which lasts 11 weeks in total – it starts over again. In September, Blippo+ was also released in color for Windows and Nintendo Switch, but in this version, developed with Noble Robot, players advance through time by unlocking packages containing the programs of successive weeks, and can always revisit earlier ones. Week by week (or package by package) a broader narrative unfolds – one that speaks of this improbable alien contact through television, of information control, of community and revolution. And of ghosts, because Blippo+ is above all a ghost story.

Even the name of the planet “Blip” recalls in English a “ghost image” left on the screen. As Jeffrey Sconce explains in Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Duke University Press, 2000), since the days of the telegraph and early wireless technologies, “held the tantalizing promises of contacting the dead in the afterlife and aliens of other planets.” Blippo+ thus joins a long tradition of stories imagining what might happen if such promises were fulfilled – in this case, even simultaneously. According to what’s discovered on planet Blip, while alive, people release particles of consciousness that linger in the atmosphere after death. And thanks to a technology developed by scientist Ned Telson (played by Cosmo Segurson), these particles can be used not only to build communication systems like Blippo+ but also to talk with the dead, as Telson does in his show Brain Drain.

Precisely because it sees television as both a medium and a “median,” Blippo+ also allows us to communicate with ghosts that are far less supernatural or science-fictional. It is a hauntological work, to return to the concept of hantologie/hauntology coined by French philosopher Jacques Derrida: a work about that which, like a ghost, both is and is not – that which capitalism has tried to erase but that continues to haunt us. A ghostly apparition that reaches us fragmented and looping, through a bent space and a time out of joint. “Planet Blip is a lot like Earth,” Evans notes. “It’s sort of as if the era of public-access television and video art and early broadcast television and early cable had continued on this separate timeline.”

Blippo+ is therefore not (or at least not only) nostalgia – not a fantasy of a planet frozen 40 years in the past. Its 1980s–1990s aesthetic serves instead to tell the story of the future (now, the present) that that past had suggested but never delivered. And Blip is not an alien world but an alternate Earth – one where television is “controlled and made by artists rather than executives and capitalists,” as Bechtolt says. In this sense, Blippo+ resembles various internet aesthetics discussed by Valentina Tanni in Exit Reality (Nero, Aksioma. 2024), such as vaporwave or Frutiger Aero. “There’s something in common between the early days of cable television and the early days of the internet,” Evans states. “Before the powers that be constrained them and turn them into just machines for making money there are always these opportunities and the world of Blippo+ is like what if those powers never came along and we just got to explore those opportunities.”

Proof that Blip isn’t truly an alien world lies in the fact that Blippo+ was developed on Earth by real, flesh-and-blood human beings (whom you can see working – bloopers and behind-the-scenes – at the end of the game). It was even made with technologies that would commonly be considered obsolete, and published on a console with a 1-bit screen. This is the true haunting of the lost future: it reminds us that another present could have been possible – indeed, that it might still be possible. As British philosopher Mark “k-punk” Fisher writes in Ghosts Of My Life. Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Zer0 Books, 2014), “[t]he spectre will not allow us to settle into/ for the mediocre satisfactions one can glean in a world governed by capitalist realism,” that is, by the belief that there is no alternative to the capitalist mode of production. “Blippo+ is an invitation,” Bechtolt concludes. “It’s saying you can do this too. You can make your own TV. Another television is possible. Another world is possible.”

Matteo Lupetti writes about art criticism, digital art and video games in publications such as Artribune and Il Manifesto and abroad. He has been on the editorial board of the radical magazine menelique and the artistic direction of the reality narrations festival Cretecon. His first book is ‘UDO. Guida ai videogiochi nell’Antropocene’ (Nuove Sido, Genoa, 2023), a reinterpretation of the video game medium in the age of climate change and within the new multidisciplinary paths that foreground the non-human and its agency.