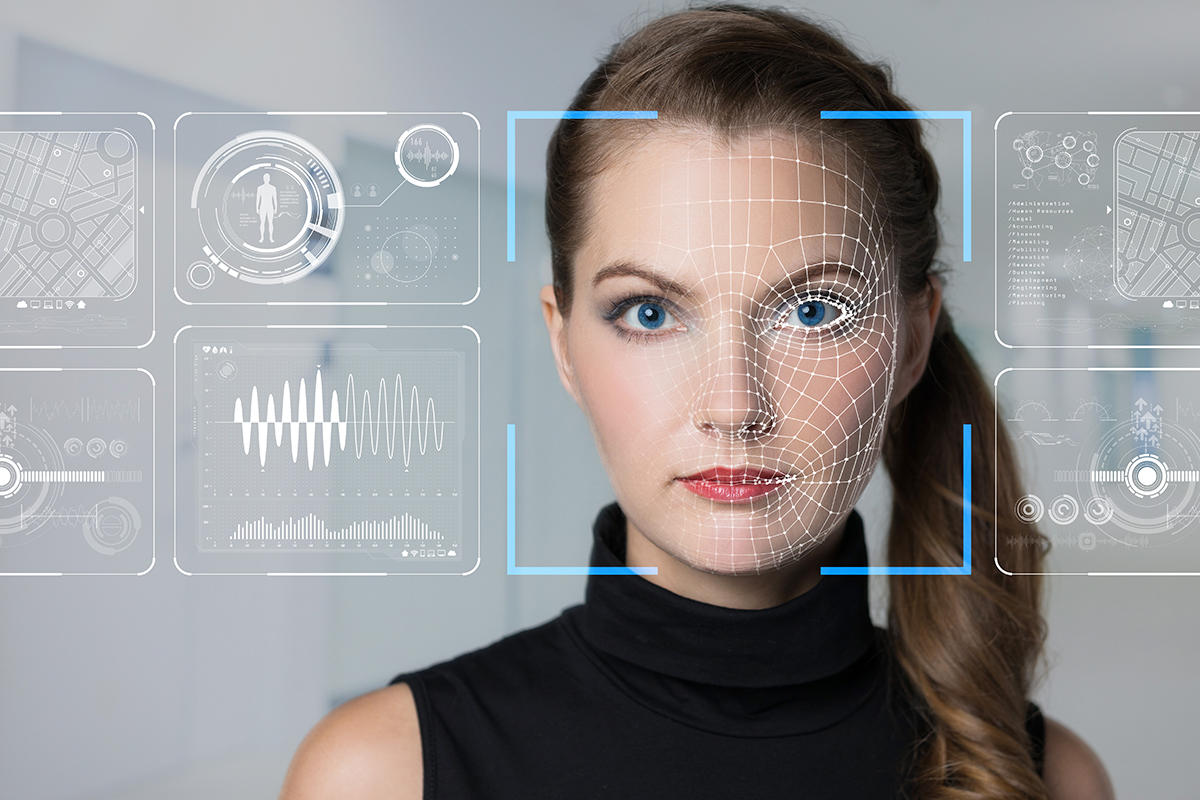

Denmark has introduced a bill that could forever change the way we address the issue of deepfakes. The proposal, supported by a large majority in the Folketing—the Danish Parliament—stipulates that the body and voice should be protected by copyright law in the same way as an artistic work. In other words, each individual’s physical and vocal identity would become an intellectual property of which the person is the exclusive owner. If approved, the law would make it possible to demand the immediate removal of unauthorized content and to seek compensation without having to prove specific damages.

“Everyone has the right to control their own face and voice,” said Culture Minister Jakob Engel-Schmidt, summarizing the scope of the reform.

The Danish model represents a revolutionary innovation. Until now, the protection of individuals online has relied on criminal law, defamation, and privacy regulations—tools often too slow and ineffective in the face of digital speed. With this proposal, identity itself becomes subject to copyright, and anyone exploiting it without consent would be committing a violation subject to immediate sanction. Digital platforms would be required to remove infringing content promptly and could face heavy fines for failure to act. Exceptions are provided for satire and parody, in order not to stifle freedom of expression, but the underlying principle is clear: to stop the spread of manipulated content at its source, especially of a sexual or political nature.

Recent events in Italy highlight just how necessary such a tool could be. The Phica.net case, for instance, shocked public opinion: thousands of intimate images, stolen or manipulated—often taken from social networks—were published without consent. In some cases, victims were forced to pay for their removal. Adding to the outrage was the exposure of the Facebook group “Mia Moglie” (“My Wife”), with more than 30,000 members, where private photos of partners were shared without consent, accompanied by vulgar and sexist comments. These episodes revealed the inadequacy of current tools: images spread in minutes, while justice arrives months or years later—when the damage is already irreparable.

If the Danish proposal becomes law, it could serve as a model for the entire European Union. However, there are risks. First: extraterritorial application. Many deepfakes are created and circulated outside Denmark, and it is difficult to imagine global platforms complying with national rules without a common European framework. Second: defining what constitutes a violation. Where does legitimate creative or journalistic use end and abuse begin? Without clear criteria, there is a risk of rising litigation. Third: the conflict with freedom of information and art. While the law would protect victims, it could also be used to remove controversial content, political satire, or investigative reconstructions. Fourth: technical costs for platforms, which would have to implement advanced monitoring and removal systems—raising the risk of automated censorship that is excessive or indiscriminate. Finally: the overlap with existing instruments such as the GDPR and the Digital Services Act, which could lead to regulatory contradictions and redundancies.

Despite these challenges, the symbolic and political value of the proposal is undeniable: transforming bodily and vocal dignity into a copyright, making each person both author and guardian of their own identity. In Italy and across Europe, recent cases show that this issue can no longer be postponed. The challenge will be to harmonize this new concept with fundamental freedoms and the global context.

If Denmark succeeds in its goal, it will not merely have passed a law—it will have sent a universal message: in the age of artificial intelligence, the human being cannot be reduced to a manipulable tool, but remains the sole and inviolable owner of their own image and voice.

Is a graduate in Publishing and Writing from La Sapienza University in Rome, he is a freelance journalist, content creator and social media manager. Between 2018 and 2020, he was editorial director of the online magazine he founded in 2016, Artwave.it, specialising in contemporary art and culture. He writes and speaks mainly about contemporary art, labour, inequality and social rights.