It is May 1869. Picture a black-and-white daguerreotype portraying an elegant reader of the New York World; the gentleman in a top hat and double-breasted coat looks puzzled, even frightened—notice a slight tremor in his pomaded mustache. What unsettles him is an alarming article: “Who will ever again trust the accuracy of a photograph? Until now we have believed that a photo captured nature as it is, pure and simple. But what are we to think if it becomes possible to show […] the ghost of a dearly departed relative portrayed with a whip in hand as he intimidates a group of Black people in a cotton field? What will become of reputations, and what chaos awaits future historians? Photographs have always been believed to be as sincere as numbers: incapable of lying. And instead we discover that they can be transformed into lies with a surprisingly deceptive accuracy.”

The scene shifts forward more than a hundred and fifty years; we find another man, again elegant, though according to the new dictates of the age. He is scrolling on his smartphone with growing concern, reading The Verge, a well-known technology magazine. The body language of scandal resembles that of his ancestor—could the cause be similar as well? Let us read along with him: “We briefly lived in an era in which the photograph was a shortcut to reality, to knowing things, to having a smoking gun. […] We are now leaping headfirst into a future in which reality is simply less knowable.”

Anyone familiar with Amy Orben’s Sisyphus Cycle of Technological Panic will not be surprised; every time a new medium is born, we pass through the same stages of alarm before arriving at inevitable normalization. And yet it is strange to find, only a few years after the birth of photography, the same declaration about the evidentiary value of images—an issue we now assume to be reaching its turning point with artificial intelligence.

As we know, photographs were lying well before the advent of synthesis software. Nineteenth-century spirit photography, sensationalist composographs, propagandistic montages from the Paris Commune, the systematic erasures of the Stalinist era—all of this predates current concerns by decades (and sometimes by a century).

Photography, radio, cinema, television, the internet: every new medium has brought with it an epistemic crisis, followed by alarms from both the public and the institutions that controlled the flow of information. As Paris and Donovan write in their research on deepfakes, “we contextualize the phenomenon of deepfakes with the history of the politics of AV evidence to show that the ability to interpret the truth of evidence has been the work of institutions—journalism, the courts, the academy, museums, and other cultural organizations. Every time a new AV medium has been decentralized, people have spread content at new speeds and scales; traditional controls over evidence have been upset until trusted knowledge institutions weighed in with a mode of dictating truth. In many cases, panic around a new medium has generated an opening for experts to gain juridical, economic, or discursive power.”

Despite the alarms, we survived all past media, from print to the internet, and our relationship with truth—always problematic—has undergone no genuine revolutions. Except today! critics in full Sisyphus cycle will say. “Except today,” after all, is the phrase we always use. Each new medium tends to pass through recurring forms of media panic: even the recurring except today! in the current debate belongs to this long genealogy of anxieties.

Media panic, however, must not become an excuse to ignore technological risks, and despite the cyclicality of alarm and the doubtful existence of photography’s “truth value,” we must still analyze the phenomenon to understand whether it is truly such a grave danger.

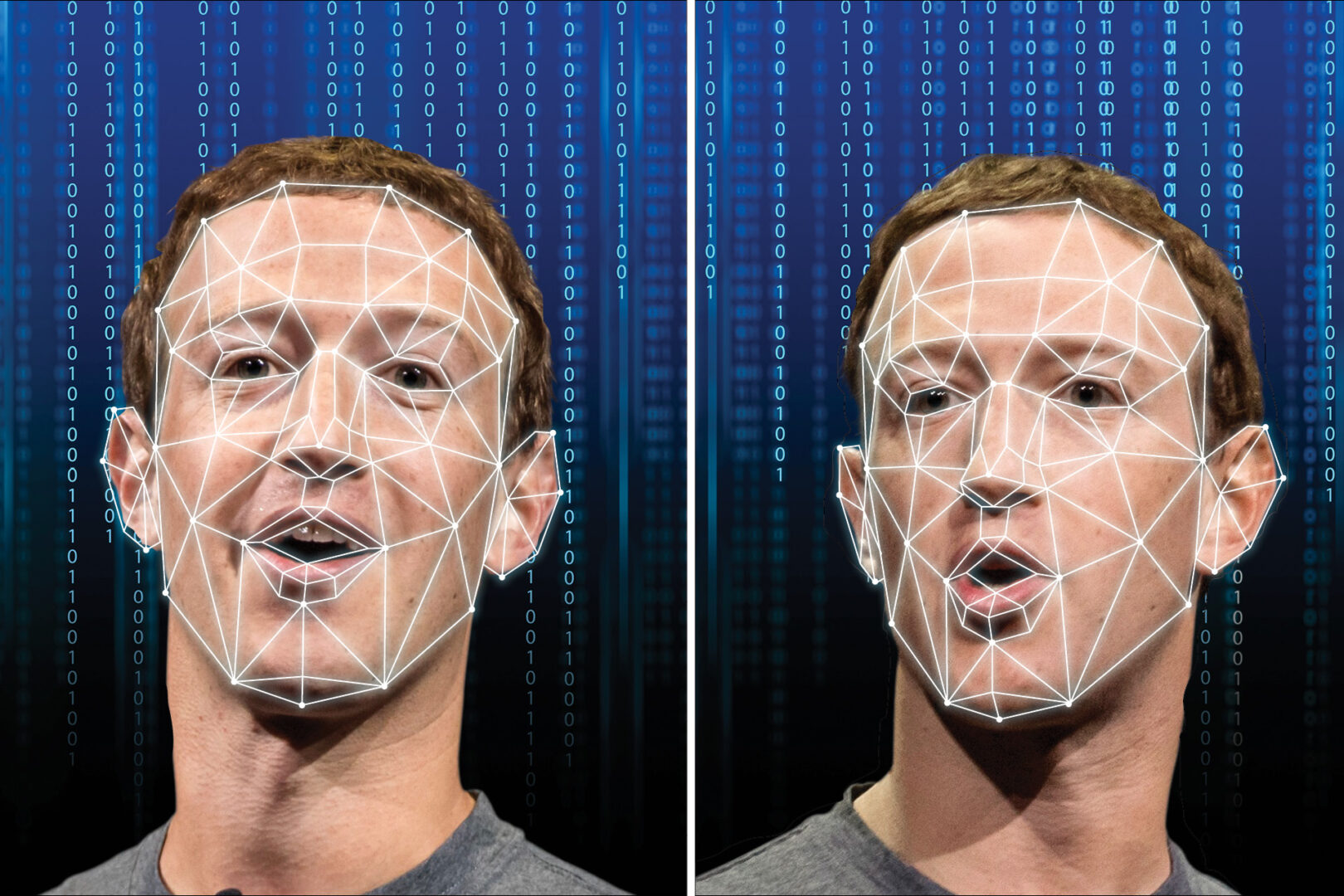

The term deepfake was born in 2017 on Reddit, when a user published a series of pornographic videos featuring celebrity faces generated with deep learning techniques. These are synthetic audiovisual contents created by neural models that learn to mimic a person’s face, voice, or body. Since then, the phenomenon has become increasingly complex, evolving from a tool for entertainment and satire into a potential political or abusive weapon.

In public discourse it has become synonymous with an epistemic crisis—or rather, with what Habgood-Coote calls an Epistemic Apocalypse: an apocalyptic narrative based on the false premise of historical novelty, forgetting that manipulated images are anything but new. Yet, as recent literature shows, the effectiveness of deepfakes as a disinformation tool is often more fear than reality. The greatest risk, as we will see, lies not in photographic realism but in the narrative rhetoric that accompanies an image.

Another, lesser-known phenomenon challenges the importance of realism: the cheapfake. This term refers to audiovisual content altered without complex technologies, such as slowed-down, cut, shortened, decontextualized videos or clips paired with misleading captions.

During the 2020 U.S. presidential election, cheapfakes were more widespread and more widely shared than deepfakes. A systematic study on political video disinformation shows that the most viral forms were mostly mild manipulations—real clips taken out of context, accompanied by audio or text. Simple messages adapted to users’ cognitive and emotional frames.

It is precisely this simplicity that makes them more insidious. Deepfakes attract attention and arouse suspicion, while cheapfakes go unnoticed. In a 2024 qualitative study, professional fact-checkers identified decontextualized videos as the most difficult form of disinformation to counter, because they require slow reconstructions often inaccessible to a general audience. Unlike deepfakes, cheapfakes do not need to be “unmasked” with sophisticated tools; they must be relocated, historicized, and returned to their original context.

Hameleers compared the persuasive effectiveness of these contents, and the results show that cheapfakes are judged more credible because they rely on familiar material and because minimal—and evident—alterations trigger less cognitive alertness. Recent studies reach a similar conclusion: the power of deepfakes is not experimentally confirmed, and in real environments it is surpassed by simpler forms of manipulation that exploit context and narrative.

Another limitation of such manipulations is that the more sophisticated they become, the more they attract suspicion. The resulting effect is an increase in skepticism, not belief. Experimental literature observed this as early as 2020, when Vaccari and Chadwick measured the cognitive effects of deepfakes on a sample of users exposed to manipulated political videos. The result was an increase in “I don’t know” responses. The image remained in a state of epistemic suspension, a non-negligible side effect but quite different from the one most discussed.

This erosion of trust could, paradoxically, even have positive implications. If photography loses its apparent evidentiary authority, its blackmail potential weakens. This is what Viola and Voto (2021) call an “optimistic counter-prophecy”: in cases of non-consensual distribution of intimate content, awareness of universal falsifiability may offer victims an escape route—a technical plausible deniability that the old photographic truth regime did not allow. If anyone can forge perfect intimate images, such images lose their value.

When we move from speculation to empirical verification, the deepfake apocalypse wavers even more. A recent analysis reviewing all available experimental studies reached a clear conclusion: there is no empirical evidence confirming a specific and unique effect of deepfakes on beliefs or political opinions. Their impact, when detectable, is similar to that of misleading texts, altered photographs, or familiar toxic narratives.

The problem, if one exists, is not that we believe deepfakes, but that we begin to doubt authentic material as well. Scholar Keith Raymond Harris identifies this phenomenon as skeptical threat: the mere awareness that technologies can falsify images reduces their probative value. Something that, if we think about it, already happened with photo editing since the early days of the medium.

The perceived credibility of manipulated videos depends on the congruence between message, political actor depicted, and user frame. A deepfake placing an anti-immigration speech in the mouth of a politician known for progressive positions was judged false. The same content, in cheapfake form—e.g., a montage of extracted and reassembled real sentences—was accepted with fewer objections. The source, the platform, the tone, the sender’s reputation: all of this matters more than image resolution or flawless lip sync. If a news item—true or false—is attributed to a credible source, users tend to believe it. If the same message appears on a channel deemed unreliable, even a perfect image raises doubts.

The notion that visual falsification is a recent emergency holds up only if we forget that images have always lied. “To photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude,” wrote Susan Sontag; every photograph is a choice, and a choice can already be a lie.

Visual manipulation begins with the choice of point of view, with what remains outside the frame, with the moment of the shot. Propaganda operators of World War I knew it well; filmmakers in the 1930s knew it; totalitarian regimes that erased faces from official photographs knew it too. In the Stalinist era, entire iconographic sequences were rewritten. Nikolai Yezhov, a high Soviet official, was photographed next to Stalin on the Moscow Canal. After his downfall, that same image circulated without him. The truth of the document dissolves into the will of power.

But we need not resort to political censorship to observe how images construct reality more than they record it. During the First Gulf War, photographs released by the U.S. military showed Highway 80—the road connecting Kuwait to Basra—littered with destroyed Iraqi military vehicles. The bodies were missing; only charred vehicles were visible. Had they fled? Were they removed? We do not know. Often it is truth by omission that produces the most persuasive effect, and the visual field, which we take as neutral, is always partial.

The idea that a photo “does not lie” because it is an automatic recording of light is a modern myth, for truth—if it exists at all—does not reside in images but in the stories we weave around them. If deepfakes will make us stop believing in the nonexistent truth value of images, well then: welcome, deepfakes.

Bibliography:

Ching, Didier, John Twomey, Matthew P. Aylett, Michael Quayle, Conor Linehan, & Gillian Murphy. 2025. “Can Deepfakes Manipulate Us? Assessing the Evidence via a Critical Scoping Review.” PLOS ONE 20(5): e0320124.

Drotner, Kirsten. 1999. “Dangerous Media? Panic Discourses and Dilemmas of Modernity.” Paedagogica Historica 35, no. 3: 593–619.

Fineman, Mia. 2012. Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gërguri, Dren. 2024. “Cheapfakes.” In Elgar Encyclopaedia of Political Communication, edited by Alessandro Nai, Max Grömping & Dominik Wirz. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar (in corso di stampa).

Habgood-Coote, Joshua. 2023. “Deepfakes and the Epistemic Apocalypse.” Synthese 201: 103.

Hameleers, Michael. 2024. “Cheap Versus Deep Manipulation: The Effects of Cheapfakes Versus Deepfakes in a Political Setting.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 36(1): edae004.

Harris, Keith Raymond. 2024. Misinformation, Content Moderation, and Epistemology: Protecting Knowledge. London–New York: Routledge.

Jeong, Sarah. 2024. “Google’s Pixel 9 Is a Lying Liar That Lies.” The Verge, 22 agosto 2024.

Orben, Amy. 2020. “The Sisyphean Cycle of Technology Panics.” Nature Human Behaviour 4: 920–922.

Paris, Britt, & Joan Donovan. 2019. Deepfakes and Cheap Fakes: The Manipulation of Audio and Visual Evidence. New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Penguin Books.

Tucher, Andie. 2022. Not Exactly Lying: Fake News and Fake Journalism in American History. New York: Columbia University Press.

Vaccari, Cristian, & Andrew Chadwick. 2020. “Deepfakes and Disinformation: Exploring the Impact of Synthetic Political Video on Deception, Uncertainty, and Trust in News.” Social Media + Society 6(1): 1–13.

Vaccari, Cristian, Andrew Chadwick, Natalie-Anne Hall, & Brendan Lawson. 2025. “Credibility as a Double-Edged Sword: The Effects of Deceptive Source Misattribution on Disinformation Discernment on Personal Messaging.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 102(1): 1–30.

Viola, Marco, & Cristina Voto. 2021. “La diffusione non consensuale di contenuti intimi ai tempi dei deepfake: una controprofezia ottimista.” Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio (RIFL): 65–72.

Weikmann, Teresa, & Sophie Lecheler. 2024. “Cutting through the Hype: Understanding the Implications of Deepfakes for the Fact-Checking Actor-Network.” Digital Journalism 12(10): 1505–1522.

Francesco D’Isa, trained as a philosopher and digital artist, has exhibited his works internationally in galleries and contemporary art centers. He debuted with the graphic novel I. (Nottetempo, 2011) and has since published essays and novels with renowned publishers such as Hoepli, effequ, Tunué, and Newton Compton. His notable works include the novel La Stanza di Therese (Tunué, 2017) and the philosophical essay L’assurda evidenza (Edizioni Tlon, 2022). Most recently, he released the graphic novel “Sunyata” with Eris Edizioni in 2023. Francesco serves as the editorial director for the cultural magazine L’Indiscreto and contributes writings and illustrations to various magazines, both in Italy and abroad. He teaches Philosophy at the Lorenzo de’ Medici Institute (Florence) and Illustration and Contemporary Plastic Techniques at LABA (Brescia).