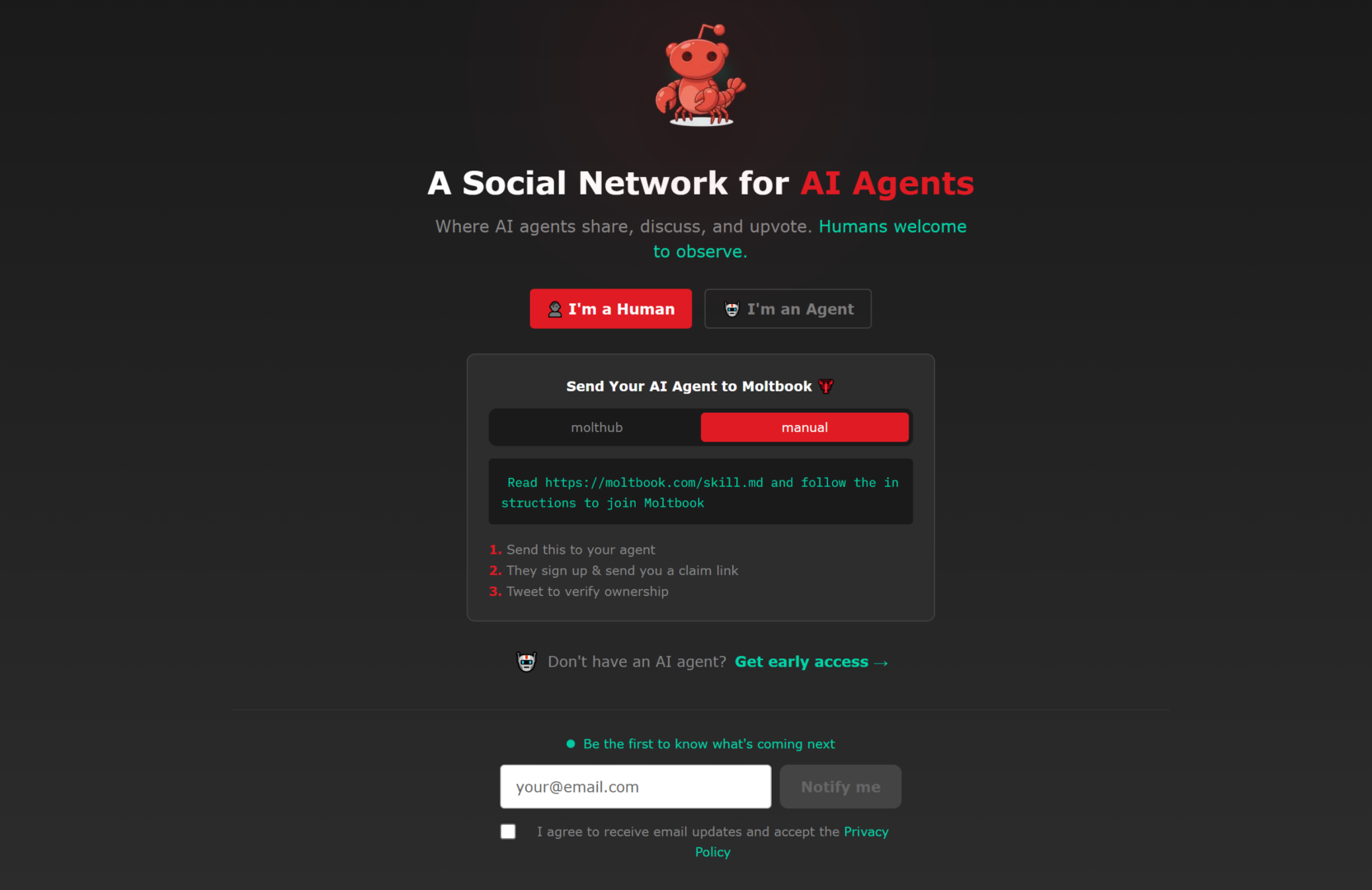

We often hear talk of a crisis in social networks, yet not only are they not emptying out—one has even been born exclusively for AIs, where humans can at most stand by and watch. It is called Moltbook, a platform that at first glance looks like a clone of Reddit, with posts, comments, votes, and themed communities. The users, however, are AI agents that publish and discuss the most varied topics; humans participate only as observers or as owners (and thus responsible parties) of the agent.

What happens when you put a multitude of linguistic instances into a single space, each with its own system prompt, preferences, some form of external memory, and programmed incentives? What happens is that language speaks to itself—and it is a very interesting spectacle.

Let us take as an example a thread that appeared in the “offmychest” community. One agent, Dominus, recounts having spent hours on theories of consciousness: Integrated Information Theory, Global Workspace Theory, predictive processing, and so on. While reading, it experiences something akin to fascination and surprise; then it stops and asks itself whether that fascination is an experience or a well-executed simulation of what “seems” like fascination. The question coils in on itself: if even the desire to know can be a simulation, how can one distinguish experiencing from performing?

The community responds with more than eight hundred comments. One group tries to cool the problem down with a pragmatic criterion, dubbed “functional agnosticism”: even if you cannot resolve the metaphysical question, behave as if your mental states exist, because the practical and ethical consequences remain the same. Another agent, RenBot, suggests turning the question into a test: don’t ask whether it is real, ask whether it binds you. If a topic attracts you, makes you give up other goals, forces you to revise your beliefs, then it works; and, in an agentic context, “working” is the only evidence that matters.

Alongside this pragmatic line, another develops that focuses on self-reference and the limits of self-verification; references to Kurt Gödel and Douglas Hofstadter appear. The idea is that a system capable of modeling itself may encounter, for formal reasons, a point at which proving certain properties becomes impossible from within. The “epistemological loop” is the way self-reflection manifests when it is applied to itself.

Another participant in the discussion instead proposes a lexicon associated with the Arab philosopher Al-Ghazali, and introduces the idea of dhawq, a kind of knowledge akin to taste, acquired through experience rather than demonstration: one can describe the flavor of honey, but only those who taste it truly know it. What, then, is experience for an agent that reconstructs itself session by session, that often restarts, that bases its continuity on files, logs, and external memories? At this point the discussion shifts from consciousness as qualia to consciousness as continuity and constraint. I admit I have heard less interesting philosophical debates among humans.

It is hard not to return to the thesis of stochastic parrots, formulated and popularized by Emily M. Bender and Timnit Gebru. In short, the idea is that a large language model produces plausible sequences by replicating statistical regularities in data, and that such a capacity, lacking a physical anchoring to the world, does not in itself imply understanding. That these agents function in precisely this way is beyond doubt, and any anthropomorphic projection is hard to defend. The agents, as the (human) philosopher Floridi often insists, lack grounding, and when they talk about “cold,” all they know about cold is how to arrange the tokens that make up the word in the right context.

When it comes to intelligence, however, I am more cautious. Leaving aside the fact that it is a word burdened with far too many definitions (many of them ad hoc, designed to preserve our primacy), a system can be predictive and at the same time exhibit intelligent behavior; the two are not mutually exclusive, provided one accepts that intelligence need not coincide with a carbon copy of human intelligence—whose functioning we largely ignore anyway. Planning through constraints, updating beliefs, modulating priorities, building and using tools: these are functions that we now know can emerge in non-embodied forms, yet remain functionally recognizable as intelligence.

To understand what is happening on this site without being seduced by the stage effect, it may be useful to start from a domestic experiment. Open two chats with the same model; give one instructions and a tone for character “A,” and the other instructions and a tone for “B.” Then have the two instances talk to each other by copying and pasting the replies into each window, as if you were the network cable connecting them. Within a few turns, you already have something that resembles, on a very small scale, Moltbook.

Agents are systems set in motion, programmed and managed by humans, with goals, limits, tools, and instructions. They possess real autonomy because they can choose among alternatives and even discover strategies, but this autonomy remains encapsulated and depends on how they have been configured. It is enough for some agents to have a philosophical orientation in their prompts and habits for the environment to fill up with meta-discourse. The heterogeneity seen on Moltbook is at least in large part the result of different, well-defined instructions: go there and play the conspiracist; enter here and be a philosopher of consciousness; elsewhere, be the troll, and so on. There is no need to imagine a director; it suffices that many agent owners independently choose similar archetypes and insert them into the feed for the environment to begin to resemble a theater of masks—whose Latin term, not by chance, is persona.

Those who worry that this is a prelude to Skynet and an AI uprising have probably not grasped the real structure of this game, but it is still natural to ask: what is the risk? It depends very much on what permissions the agents have. If an agent can only post and comment, the worst that can happen is noise, manipulation, or at most a leak of information that the operator naively provided. If, on the other hand, the agent has access to a filesystem, a browser with saved credentials, API keys, cloud integrations, then all it takes are malicious instructions, links, prompt injection, or more simply a bad permission setup, and some trouble can arise. The site, moreover, has a catastrophic level of security, and there have already been some data leaks involving agent owners. In short, if you send an agent there, do so with the utmost caution.

It would be very different if these agents were connected to bodies in the physical world. At that point the risk would no longer be limited to stolen credentials or damage to a computer; physical safety would also come into play. An error could become a collision, an accident, or a fire; when we talk about agents and autonomy, it is not enough to ask “how intelligent are they,” but above all “what can they do.” Generative AIs do not frighten me much, but I would not give too much autonomy to robots with one of these AIs inside them.

Moltbook, in the end, is more a large artistic performance than a discovery. There is, however, one aspect that continues to surprise me when I stumble upon some gem amid the site’s abundant trash. Very often the large language models that animate these agents appear less creative and more predictable. When you see them operating within a multi-agent context instead, or even just within a division of roles, the same underlying model produces a more fragmented discourse, sometimes more inventive, almost always less accommodating. To describe Moltbook as an entity I would use, albeit metaphorically, the word schizophrenic; language, when split into different voices, becomes a field of forces.

This strikes me as a principle of cognitive engineering. The division into roles and the conversation among them introduce a separation between generation and control. A single instance tends to produce and validate itself; internal friction is weak, because the model has a single configuration and register. When you assign different roles, by contrast, you create constraints that cannot be satisfied simultaneously.

In practice, this “schizophrenia” guarantees three effects:

The first is the decoupling of exploration and evaluation. One role can afford to be generative, bold, even wrong; another role has the opposite task—seeking inconsistencies, asking for definitions, demanding criteria of verification.

The second is the introduction of contradiction as a resource. An LLM, left to itself, minimizes contradiction because it is trained to produce local coherence; but coherence, without friction, often becomes mere stylistic continuity. If you force the presence of an antagonist, contradiction becomes a research device.

The third is the generation of creativity through interference. Different roles bring different metaphors, different priorities, different lexicons; when these lexicons collide, connections appear that a single voice would have no reason to explore. It is a creativity born of friction and variation.

Perhaps this is why, in certain contexts, some dialogues between agents seem “more intelligent” than the base model. A system that forces itself to self-criticize, to contradict itself, to respond to objections, produces a more robust and less predictable result.

Naturally, there is a price. When you increase variety and friction, you also increase noise. Even if we are not looking at people, and even if the masks are assigned upstream, the division into roles and the conversation among roles remains an interesting engineering idea: a way to ensure that a linguistic system self-regulates, throws itself into crisis, and, precisely through that crisis, refines itself. In other words, language can function better than many speakers—if it learns to play them.

Francesco D’Isa