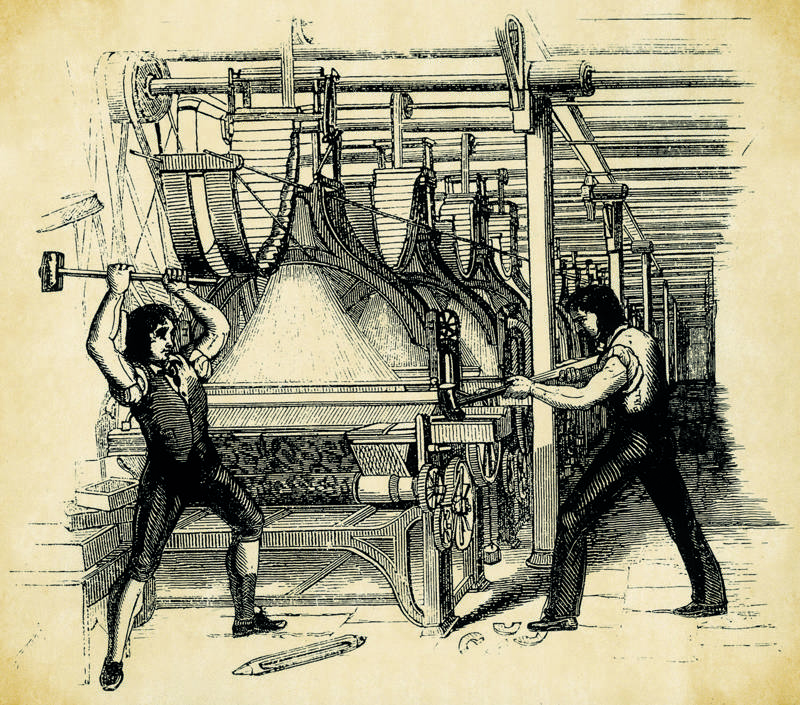

When someone today is branded a “Luddite,” the image that comes to mind is that of a killjoy who hates technology on principle, a boomer who would like to turn off computers and go back to candlelight. It is a convenient label, useful for shutting down a discussion before it even begins. Yet the story is far more complex than that. The term “Luddites” originally referred to English textile workers who, between 1811 and 1816—especially in areas such as Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, and Lancashire—organized nighttime raids against looms and the new machinery introduced into factories. They were not primitive peasants terrified of progress, but highly skilled artisans, often experts precisely in the use of the machines they went on to attack. Their target was not technology as such, but the way factory owners used it, deploying cheaper looms to replace skilled labor with lower-paid workers, thereby worsening wages and living conditions.

The very name of the movement refers to a figure hovering between history and myth: “Ned Ludd” or “General Ludd,” the supposed worker who in 1779 allegedly destroyed two looms in a workshop in Anstey, Leicestershire, later becoming a symbol of collective anger against machines perceived as tools of exploitation. The Luddites signed threatening letters to employers and authorities in his name, donning the guise of a kind of industrial Robin Hood operating from the shadows of Sherwood. More than an anti-technological terrorist, Ned Ludd is the ghost of a question that still concerns us today: at what point does a machine cease to be a tool in the service of those who work and become a device of control in the hands of those who rule?

Thomas Pynchon, in his essay Is It O.K. To Be A Luddite?, published in The New York Times in 1984, had already tried to put things back into perspective: Luddism, he wrote, is not an irrational phobia of machines, but a rebellion against an “emerging technopolitical order” that uses innovation to concentrate capital and power, pushing humans “out of the game.” Today artificial intelligence is the new machine whose miracles and wonders are being celebrated, and it is no coincidence that The New Yorker chose the Luddites as a guiding thread for asking “How to survive the A.I. revolution”: the problem is not the algorithm in itself, but who decides how it is designed, for what purpose, and who reaps the profits.

Here the critical genealogy traced by sociologist Jathan Sadowski in The Mechanic and the Luddite: A Ruthless Critique of AI and Capitalism proves useful, as he shows how technology and capitalism are two intertwined systems: capital forges the technical tools it needs and then turns them against workers, users, and territories. In his reading, the Luddite is not the blind saboteur who hates computers, but the figure who asks when a machine should be switched on, whom it truly works for, and in which cases it should instead be stopped, redesigned, or dismantled. It is a political stance before it is a technical one: a refusal of the idea that every form of automation is “natural,” neutral, and inevitable.

The question “who controls the machines?” also runs through Giuliano da Empoli’s latest book, The Age of Predators, in which the author describes the alliance between new autocrats and the conquistadors of technology: engineers of chaos who use algorithms and platforms to amplify anger and frustration, turning them into consensus, profit, and geopolitical power. It is no coincidence that Europe’s political class reads da Empoli to understand how this new class of “predators” operates, yet still struggles to take a clearer and more radical position: as long as digital infrastructures, data, and AI models remain concentrated in a few private hands, the promise of “democratizing” artificial intelligence will remain largely a slogan.

Even Geoffrey Hinton, one of the fathers of deep learning, now speaks openly about the need for some form of “AI socialism.” In an intervention analyzed by researcher Thorsten Jelinek, he is described as increasingly skeptical of market regulation alone and inclined to imagine models of public or collective control over the fundamental infrastructures of artificial intelligence, from data centers to foundation models. It is an idea that sounds radical only because we have normalized the opposite: that the planet’s cognitive future should be managed like any other proprietary asset.

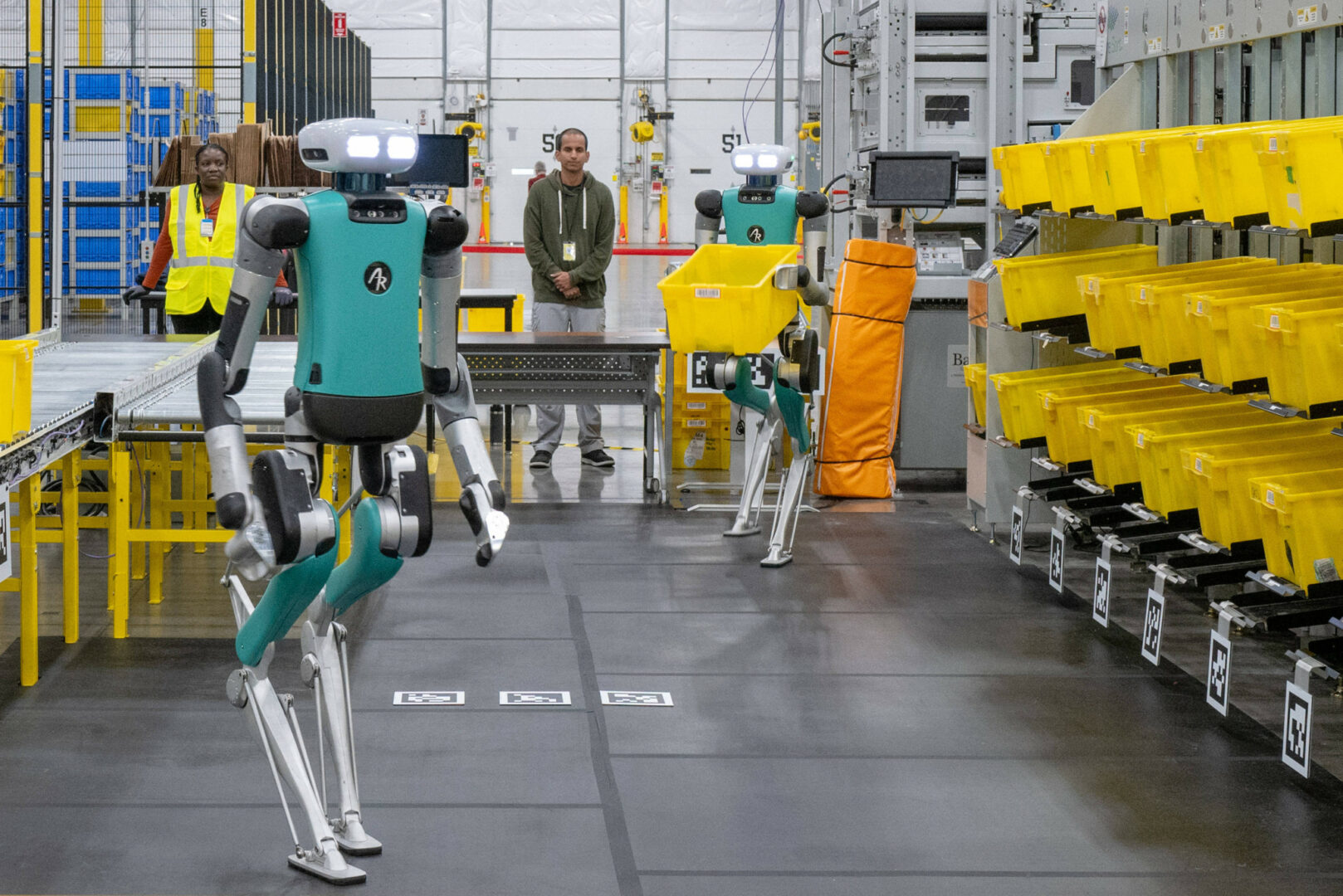

Meanwhile, while abstract debates about existential risks continue, automation is moving fast and is already claiming its first victims. An internal Amazon document revealed by The New York Times shows that the e-commerce giant aims to automate up to 75 percent of its warehouses by 2033, thereby avoiding more than 600,000 new hires in the United States thanks to robots and AI systems. There is no talk of mass layoffs, but the result is similar: entire pools of low-skilled jobs that will simply never be created, because they are deemed replaceable by machines. It is the translation, into figures and corporate slides, of what the Luddites were rebelling against two centuries ago: every new machine is not only efficiency, but also a certain number of working lives deemed expendable.

Today’s “neo-Luddites”—trade union activists, critical researchers, technologists who have defected from Silicon Valley—do not propose a return to candlelight, but a rethinking of this implicit pact. They demand that automation not be a means to compress wages, further precarize labor, or offload environmental costs onto already vulnerable communities. In different forms, they claim that the benefits of AI should be distributed, and that those subject to algorithmic decisions should have a voice in shaping them. In this sense, Luddism is not the childish rejection of the machine, but the adult demand to collectively decide which machines we want, under what conditions, with what limits, and with which mechanisms of democratic control.

Perhaps, then, the question to ask today is not whether it is acceptable to be a Luddite, as Pynchon provocatively asked forty years ago, but whether we can afford not to be one—at least a little. In an era in which artificial intelligence promises to optimize everything except the distribution of power, the true “enemies of the machine” are not those who reject technology, but those who demand that the machine cease to be the fetish of capital and return to being a tool in the hands of many, not of a very few.

Is a graduate in Publishing and Writing from La Sapienza University in Rome, he is a freelance journalist, content creator and social media manager. Between 2018 and 2020, he was editorial director of the online magazine he founded in 2016, Artwave.it, specialising in contemporary art and culture. He writes and speaks mainly about contemporary art, labour, inequality and social rights.