Contemporary debate on post-truth has fixated, almost obsessively, on deepfakes, synthetic images capable of staging events that never occurred and fabricating historical records. Yet a growing body of research, together with a careful look at the history of images, suggest that this phenomenon has been dramatically overestimated and is therefore far less widespread than many feared; what seems to be spreading is a different process, which I have chosen to call “deeptrue”.

This category includes deceptive images that depict real, historically attested, verifiable events. Their visual appearance is “improved”, amplified, or cleaned up through generative AI or other forms of retouching. Unlike radical manipulations that rewrite history, deeptrues preserve an ontological link to what happened; the aim is to make the image of a fact more presentable and effective, while keeping it anchored to the event.

The dynamic became especially clear in the clashes surrounding protest demonstrations in Turin in February 2026. An image circulated by the official social-media accounts of the Polizia di Stato showed an officer helping a colleague who had been attacked, but the image itself was artificial. Through algorithmic restoration tools, the scene was enhanced beyond the poor quality of the cropped frame taken from the original video.

A comparable aesthetic hyperbole shaped coverage of the record snowfalls in Kamchatka in January of the same year. Even though the event was genuine, its viral circulation was driven by content that exaggerated the scene through AI-assisted edits. Images of snowdrifts as tall as nine-storey buildings, or of people supposedly sliding out of windows at impossible heights, quickly appeared alongside real photographs; many outlets were taken in, because fact-checking confirmed that the snowfall itself had truly occurred.

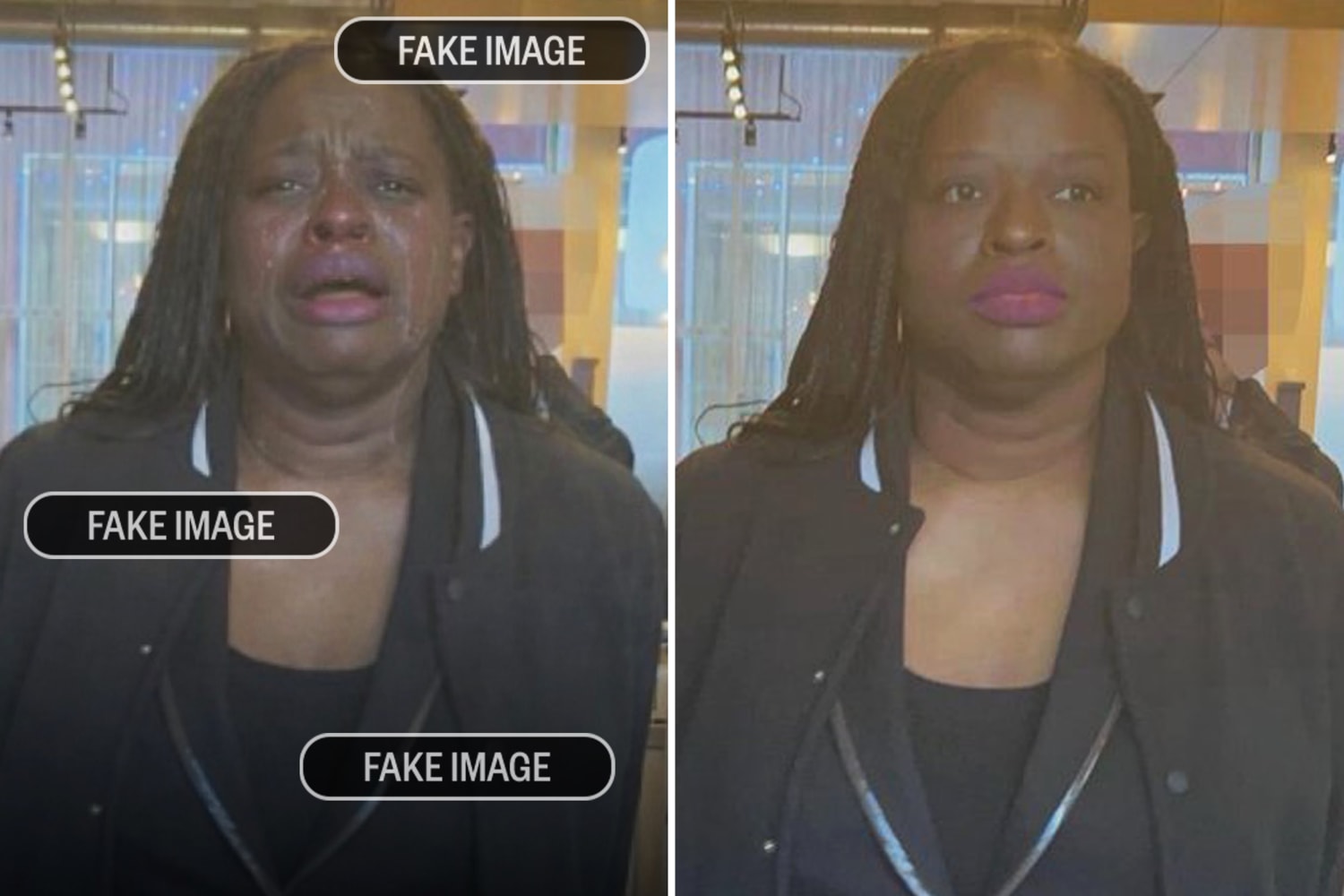

A hybrid case, also recent, emerged in the episode involving the White House and the arrest of Nekima Levy Armstrong by the notorious ICE. The original photograph showed the woman with a neutral, composed expression; the version released through official channels had been altered to make her appear in tears. The edit does not deny that the arrest took place, yet it adds a manufactured emotional layer that serves a specific narrative of the opponent’s defeat or weakness. Here an actual falsification occurred and, as often happens, it was swiftly exposed; that makes the benefit gained by an institution like the White House questionable at best, especially given the awkward position of having to justify the use of blatantly fake imagery.

Susan Sontag noted that photography has always carried a mandate to ennoble the visible. Any object or condition, once framed, tends to become “interesting” through a deliberate authorial choice. In Edward Weston’s famous photograph of a toilet bowl, for instance, the ennoblement comes from isolating an elegant, solemn form from a prosaic setting. Analog photography works largely through exclusion. The photographer cuts out a fragment of space-time, discards the rest, and compresses the immensity of the real into a well-defined instant.

This dynamic of selection does not concern only the person who takes the picture. As Zeynep Devrim Gürsel argues in Image Brokers, the circulation of news images has always been mediated by professional figures such as editors, agencies, and archivists, who function as brokers of the imaginary. These intermediaries build what Gürsel calls “formative fictions”, visualizations of the world designed to be immediately legible and consistent with the expectations of a global audience. The most effective journalistic image is the one that best conforms to established narrative templates, the one that confirms an iconography of pain, victory, or crisis already internalized by the viewer.

To understand the logic of deeptrue fully, it helps to examine how classical photography anticipated algorithmic intervention through the manipulation of context. A paradigmatic example, discussed by Gürsel, is the scandal that in 2001 involved The New York Times Magazine and the journalist Michael Finkel. The article, titled “Is Youssouf Malé a Slave?”, told the story of a young Malian sold into slavery on cocoa plantations. The text was accompanied by a photograph of a boy with a suffering expression, whom the public immediately identified as the protagonist.

In fact, the teenager shown was not Youssouf Malé. Michael Finkel constructed a “composite character”, merging the stories of several boys into a single narrative archetype. To illustrate this figure, he did not use Malé’s actual image. He used a photograph of another young man, Madou Traoré, whose face had the right visual match for the role of victim, regardless of his identity. Gürsel describes such operations as formative fictions, images meant to visualize a political category, the child slave, the refugee, and so forth, rather than to point to a specific individual. The editorial practice she documents, which elsewhere leads to rejecting images of Palestinians deemed “too blond” or victims who look “too modern” because they do not match the stereotype, shows how, even without fabricating an image, a real body is reshaped to coincide with audience expectations. Today’s deeptrue automates that process. AI no longer needs to find the next Madou Traoré in order to misrepresent Youssouf Malé; it can generate the “average face” of suffering on demand.

It would be a mistake, however, to imagine that this “average face” begins with artificial intelligence. It already appeared in the late nineteenth century in the laboratory of Francis Galton, Darwin’s cousin and the father of eugenics, who tried to apply statistics to the human face through composite photography. Galton’s aim was as scientifically ambitious as it was ideologically compromised. By superimposing portraits of individuals belonging to the same category, he hoped to isolate physiognomic traits associated with criminality, illness, or health.

To do so, Galton photographed a series of subjects, for example men convicted of violent crimes, then exposed the plates one after another onto a single sheet of photographic paper, calculating fractional exposure times so that each face would contribute equally to the final image. He expected a monstrous type to emerge, a kind of mask of crime that would confirm Lombrosian theories of biological deviance.

The result defied that expectation. The composite face that emerged from the darkroom looked more beautiful, noble and harmonious than any of the individual faces that produced it. Mechanical superimposition had acted as an aesthetic cleansing filter. Asymmetries, skin imperfections and the specific irregularities of each criminal canceled one another out, leaving only shared features. Galton discovered, inadvertently, that the statistical mean, in visual terms, aligns with classical beauty or at least with the absence of conspicuous defects.

This brings to mind the analysis that Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli devote to the aesthetics of AI. Generative models learn the statistical structure of billions of images and then produce new instances that, even when novel and original, tend to cluster near the center of the dataset’s distribution. When we ask an algorithm to generate or enhance a face, it gravitates toward the most probable version given the data it has absorbed. The outcome has a kind of “statistical beauty”, a blend of aesthetic stereotypes embedded in the dataset and a visual average. The aesthetic is polished, with flaws that tend to dissolve. Reality is full of noise, irrelevant details, and accidents. The Turin clashes or the Kamchatka snowfall become “truer than true” precisely because they have lost their resistance and turned into statistically perfect icons, ready to be consumed without friction.

This process points to what I take to be the image’s most intimate nature, its ideogrammatic function. The Turin police photograph becomes an ideogram of “solidarity with the police” or “protester violence”. The Kamchatka snowfall sheds its meteorological contingency and becomes the absolute symbol of “record-breaking snow”. The struggle between ideograms is aesthetic, semantic and political. It is no coincidence that the government tried to impose one ideogram, set against the competing one, also present, of a protester being beaten by the police.

As I have argued elsewhere, the relations among image-ideograms are defined by semantic attractors, conceptual centers of gravity that steer interpretation and meaning. Just as physical gravity aggregates matter, semantic gravity compacts phenomenal reality into dense visual forms that can be decoded at a glance. The image’s nature functions less as testimony and more as a linguistic operator; it signifies, aiming to describe the world as efficiently as possible.

As Joan Fontcuberta suggests in The Fury of Images, the post-photographic image is expected to be credible, even when factual truth is flat, poorly framed, or technically weak. Credibility, by contrast, demands rigorous adherence to dominant visual codes and to audience expectations.

Deeptrue therefore answers a Darwinian necessity. If an original photograph of an event is visually confused or pixelated, its capacity to circulate through social networks is reduced, and it risks extinction within the torrential flow of content. AI intervention serves to secure the icon’s viral fitness.

This impulse to cosmetically adjust the true in order to make it credible has deep roots in media history, as shown by the visual archetype of the oil-soaked cormorant during the 1991 Gulf War. That image instantly became the symbol of an ecological disaster attributed to Saddam Hussein and shaped global indignation. Only later did it emerge that the bird had most likely been filmed in a different place and at a different time, and that the scene may have been staged for the cameras. The oil spill was real and documented, and yet data alone did not suffice. It needed an actor, the cormorant, and an effective set. Today’s deeptrue is the technological heir to that need. Reality, in order to be believed and to mobilize consciences, has to put on a layer of make-up.

A narrow focus on retouching or on forensic veracity therefore risks becoming a diversion that distracts from the real apparatus of power, the one Judith Butler, in Frames of War, identifies as the epistemic violence of framing, a “normative production of ontology”. The frame helps constitute reality. It decides which lives count as lives and which are reduced to disposable residue whose destruction fails to register as a crime, because it is not recorded as a loss.

“Grievability” is the political precondition of life. A life is considered worthy only if it is already inscribed in the register of what, in the future anterior, will have been worthy of our mourning. In this sense, war photography is a regulator of political feeling, telling us when and for whom to feel horror. For the frame to impose its hegemony and ratify the norm, it must circulate, repeat, and spread relentlessly across media. Yet Butler also sees reproducibility as a point of weakness. As an image moves from one context to another, the frame risks breaking, losing its capacity to contain the excess of reality it was designed to exclude. In systemic cracks of this kind, as happened with the viral circulation of photographs from Abu Ghraib, background noise breaks through, revealing that the image was coercively trying to produce the reality it purported to document.

To grasp the meaning of deeptrue and deepfake, one has to examine the epistemic failure of the raw image that emerged with particular force during the debate over the killing of Renee Good by ICE agents in Minneapolis. The video of the event, filmed from several angles, was authentic and technically clear; yet American public opinion split into two irreconcilable camps. One side saw, with absolute certainty, an SUV being used as an improvised weapon to run into the agents. The other side saw, with equally unwavering certainty, a car desperately trying to flee an armed threat.

This was a political reprise of the viral phenomenon known as The Dress, which in 2015 divided the world between those who saw a blue-and-black dress and those who perceived it as white-and-gold. As the neuroscientist Pascal Wallisch has shown, that split depended on the brain. Faced with ambiguous illumination, the visual system applies priors, pre-existing expectations, in order to infer the colors. Those who unconsciously assumed the dress was in shadow tended to see white; those who implicitly placed it under artificial light tended to see blue.

The Renee Good case followed the same pattern. Political identity acted as a corrective filter. Supporters of law enforcement perceived aggression; activists perceived flight. The image functioned as a moving Rorschach test in which each viewer projected prior beliefs. Cultural Cognition theory, developed by Dan Kahan, offers a framework for this. Kahan’s research shows that individuals interpret information in ways that protect membership in their reference group. This is identity-protective cognition. The brain accepts as “true” what does not jeopardize one’s standing within a political tribe. In the Renee Good video, visual ambiguity is resolved instantly by this defensive mechanism.

As tools for perpetrating deception, deeptrues are weak, since they still point toward something that happened. Their logic resembles an old, overused device of visual rhetoric, updated for contemporary conditions. Images do not simply indicate the world; they set it in motion.

Francesco D’Isa

Bibliography and References

AFP Fact Check. “Footage of massive snowfall in Kamchatka is AI-generated.” 29 gennaio 2026. https://factcheck.afp.com/doc.afp.com.94984G3.

Alvich, Velia. “La Casa Bianca ha usato l’intelligenza artificiale per aggiungere lacrime finte alla foto di una donna in manette.” Corriere della Sera, 23 gennaio 2026. https://www.corriere.it/tecnologia/26_gennaio_23/la-casa-bianca-ha-usato-l-intelligenza-artificiale-per-aggiungere-lacrime-finte-alla-foto-di-una-donna-in-manette.shtml.

Associated Press. “Police Arrest Protesters at Minneapolis Federal Building on 1-Month Anniversary of Woman’s Death.” AP News, 7 febbraio 2026. https://apnews.com/article/8cf815a6c4b20f1f79874d65c9f1361f.

Barari, Soubhik, Christopher Lucas, e Kevin Munger. “Political Deepfakes Are as Credible as Other Fake Media and (Sometimes) Real Media.” The Journal of Politics 87, n. 2 (2025): 510-526

BBC News. “Video filmed by ICE agent who shot Minneapolis woman emerges.” Video YouTube, 0:54. Pubblicato il 1 ottobre 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bcOfsg749Wk.

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso, 2009.

Capoccia, Francesca. “Il TG1 ha pubblicato un video sulle nevicate in Kamchatka fatto con l’IA.” Facta, 20 gennaio 2026. https://www.facta.news/articoli/tg1-video-nevicate-kamchatka-russia-intelligenza-artificiale.

D’Isa, Francesco. “Deepfake: anatomia di una paura.” The Bunker, 12 novembre 2025. https://www.the-bunker.it/rubrica/deepfake-anatomia-di-una-paura/.

D’Isa, Francesco. La rivoluzione algoritmica delle immagini: Arte e intelligenza artificiale. Roma: Luca Sossella Editore, 2024.

Du Sautoy, Marcus. The Creativity Code: Art and Innovation in the Age of AI. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019.

European Journalism Observatory. “Fakes in Journalism.” Consultato il 12 febbraio 2026. https://en.ejo.ch/ethics-quality/fakes-in-journalism.

Finkel, Michael. “Is Youssouf Malé a Slave?” The New York Times Magazine, 18 novembre 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/18/magazine/is-youssouf-male-a-slave.html.

Fontcuberta, Joan. La furia delle immagini: Note sulla postfotografia. Tradotto da Sergio Giusti. Torino: Einaudi, 2018.

Gürsel, Zeynep Devrim. Image Brokers: Visualizing World News in the Age of Digital Circulation. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

Hannon, Elliot, e Ben Mathis-Lilley. “The Great Blue and Black Versus White and Gold Dress Debate.” Slate, 27 febbraio 2015. https://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2015/02/26/the_great_blue_and_black_versus_white_and_gold_dress_debate.html.

Kahan, Dan M. “Cultural Cognition as a Conception of the Cultural Theory of Risk.” In Handbook of Risk Theory, a cura di Sabine Roeser et al., 725–759. Dordrecht: Springer, 2012.

Langlois, Judith H., e Lori A. Roggman. “Attractive Faces Are Only Average.” Psychological Science 1, no. 2 (1990): 115–121.

Levine, Sam. “White House Posts Digitally Altered Image of Woman Arrested after ICE Protest.” The Guardian, 22 gennaio 2026. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/jan/22/white-house-ice-protest-arrest-altered-image.

Manovich, Lev, e Emanuele Arielli. Estetica artificiale: IA generativa, arte e media. Roma: Luca Sossella Editore, 2026.

Pisa, Pier Luigi. “Scontri a Torino, la foto degli agenti aggrediti è IA. Polizia: ‘Presa dal web, non è opera nostra’.” la Repubblica, 6 febbraio 2026. https://www.repubblica.it/tecnologia/2026/02/06/news/foto_polizia_generata_ia_scontri_torino-425143065/.

Sky TG24. “Scontri Askatasuna a Torino, Polizia pubblica foto agente aggredito modificata con AI.” 6 febbraio 2026. https://tg24.sky.it/cronaca/2026/02/06/scontri-askatasuna-torino-polizia-foto-ai.

Sontag, Susan. Sulla fotografia: realtà e immagine nella nostra società. Torino: Einaudi, 2004.

Wallisch, Pascal. “Illumination assumptions account for individual differences in the perceptual interpretation of a profoundly ambiguous stimulus in the color domain: ‘The dress’.” Journal of Vision 17, no. 5 (2017): 5.