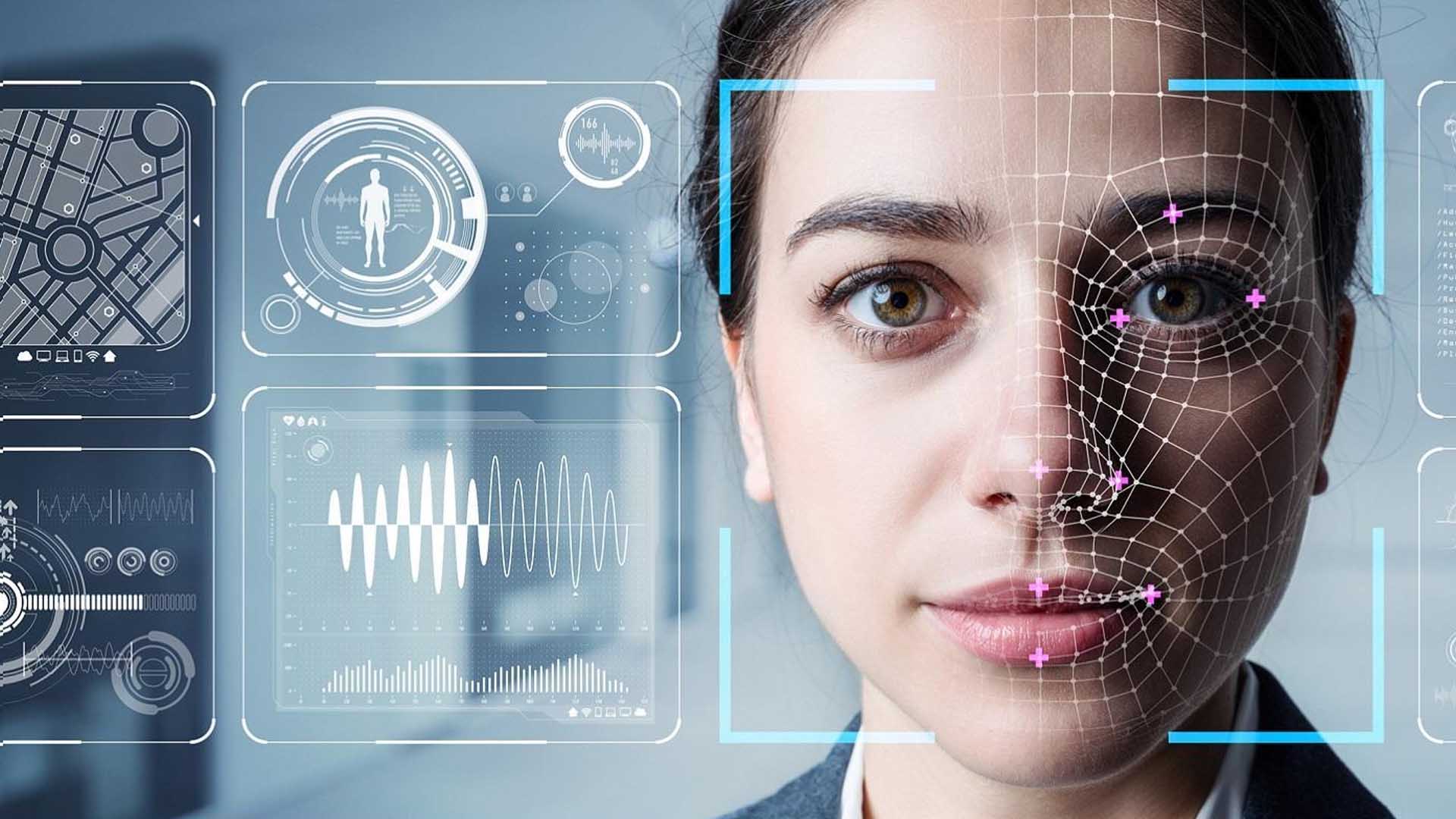

Europe is redefining the concept of a frontier. No longer lines on a map, but identity-databases where the body becomes a document and the face a password. With the introduction of the Entry/Exit System (EES) – scheduled for 2026 after various delays – the European Union will establish a huge biometric archive that will record facial images, fingerprints, personal data and the entry and exit times of every non-EU citizen.

Officially, the goal is to “speed up checks” and “reinforce security”, but in practice this proposal becomes something else: surveillance becomes automated. The data of those who enter and those who leave the Schengen area will be cross-referenced with other systems already in place, such as Eurodac or SIS II, creating an unprecedented monitoring network.

And the EU is not alone: more and more liberal democracies adopt the same tools as authoritarian regimes, justifying them with the promise of efficiency and security. From facial-recognition cameras now permanent in many English cities to apps used to track protestors in India or the United States, the border between protection and control grows ever more blurred. Europe, which presents itself as the guardian of digital rights, instead seems intent on building a permanent infrastructure of invisible surveillance. Invisible because normalised, incorporated into everyday gestures: passing a biometric check, unlocking a phone, passing through an automatic gate.

The EES is only one piece of a broader mosaic that also includes the ETIAS project, the electronic authorisation system for non-EU travellers, and the new interoperable databases managed by the agency eu?LISA. Each system will talk with the others, creating a digital ecosystem in which the citizen or the traveller will be identifiable at every step. An “algorithmic identity” that no longer just states who you are, but also where you have been, with whom you have travelled, what you have done.

The European Union is not content to digitise bodies; it has also attempted to digitise conversations. The regulation proposal dubbed by its critics “Chat Control” – proposed in 2022 by the European Commission to counter online abuse against minors – envisaged the possibility of pre-inspecting all messages, images and videos sent via messaging services, even those protected by end-to-end encryption.

On paper, a measure to safeguard the most vulnerable; in substance, a colossal system of preventive surveillance. The idea that every private message could be analysed by an algorithm however raised very harsh criticism from activists, researchers and digital-privacy organisations. Many called it “the end of encryption”, and with it the end of the freedom to communicate securely.

After months of political clash and divisions among Member States, Denmark – which currently holds the Presidency of the Council of the EU until the end of the year – finally withdrew its support for the proposal, effectively shelving it. The Danish government, which initially had backed the adoption of the regulation, recognised the impossibility of finding broad political consensus, opting for a lighter, voluntary version of the legislation.

Between the scanned face at the airport and the chat analysed by an algorithm, Europe thus draws its new digital face: an architecture of suspicion built in the name of prevention.

This is not just about technology, but about a transformation of the social contract. European democracies find themselves managing a fundamental contradiction: defending freedom through tools that limit it. It is a fragile balance. The risk is not so much immediate abuse, as the gradual habituation to control. Surveillance no longer needs to be imposed when it becomes part of daily experience. The real political issue of digital Europe is therefore not just what is controlled, but how much we are willing to accept in the name of security. Because every frontier that shifts a little further the boundary between security and liberty, between efficiency and rights, also redefines what it means to live – and think – within a democracy.

Is a graduate in Publishing and Writing from La Sapienza University in Rome, he is a freelance journalist, content creator and social media manager. Between 2018 and 2020, he was editorial director of the online magazine he founded in 2016, Artwave.it, specialising in contemporary art and culture. He writes and speaks mainly about contemporary art, labour, inequality and social rights.