Beijing hosted the first edition of the World Humanoid Robot Games, featuring races, kickboxing, and soccer matches that highlighted the progress of roboticsbut also its limits.

Let’s admit it: the thought that robots might one day steal our jobs, or a dystopian future like in the film I, Robot (2004) with Will Smith, is unsettling.

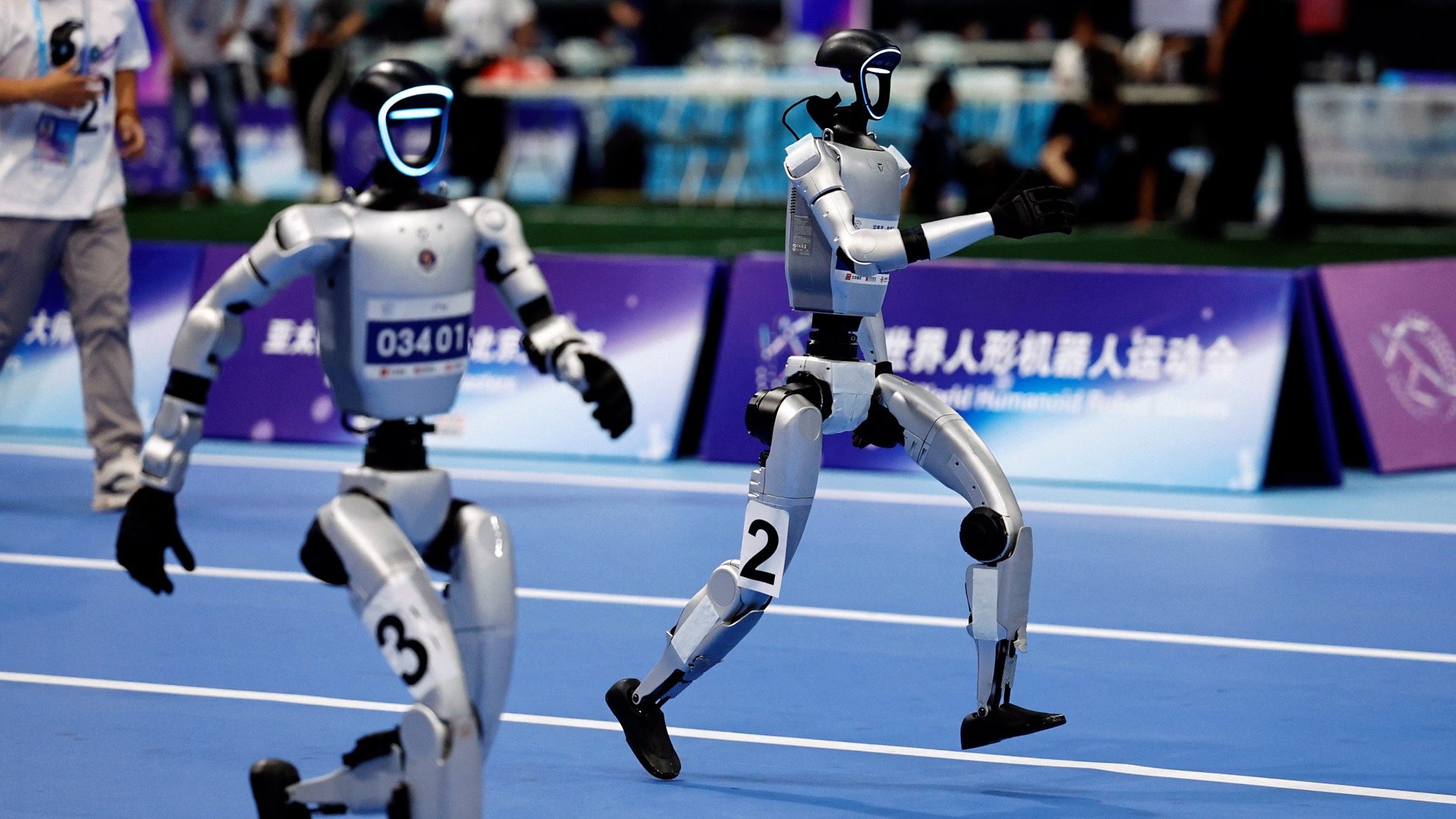

Watching them compete in sports, however, reassured us that such a future wont arrive anytime soon. Awkward, unathletic, and not exactly coordinated: thats how the participants of the first World Humanoid Robot Games, held in Beijing in August, appeared. Robotic athletes from 16 countriesincluding the United States, Germany, and Japancompeted in disciplines ranging from track and field to soccer, from dance to martial arts.

In traditional kickboxing competitions, a participants strength is measured by their physical endurance against often serious injuries. The robotic contenders who entered the ring in Beijing instead tested battery life and balance.

The World Humanoid Robot Games were essentially an opportunity to test robots decision-making, motor, and control abilitiesskills that could one day find real-life applications. No bloodthirsty robot clashes, in other words, like in the film Real Steel with Hugh Jackman, but rather simple endurance and functionality trials.

Some robots performed backflips, navigating obstacle courses and rough terrain. In other cases, their athletic skills left much to be desired. During soccer matches, for example, robots piled up and toppled over each other like dominoes, leaving just one player with the ball. After numerous failed attempts, that robot finally managed to kick it and score. Another competitor had to drop out of the 1500-meter race when its head literally flew off halfway through. One of the main difficulties, in fact, was keeping the head balanced during speed events.

Even so, a Unitree Robotics robot won the gold medal in the 1500 meters with a time of 6:34:40. Although much slower than Norwegian champion Jakob Ingebrigtsen, who holds the record at 3:29:63, the humanoid still proved faster than many amateur human runners.

The games also offered China another major showcase, following its New Years Gala in January, when dancing robots wowed the world. Social media was soon flooded with images of android marathons and influencers renting robots for a day.

Events like these, widely followed online, also reflect a more serious geopolitical reality: the intensifying tech competition between the United States and China, which could redefine the boundaries of artificial intelligence. Technology has become a key fault line in relations between the two countries. While Washington maintains leadership in frontier research and enforces restrictions on exporting advanced chips to Beijing, China is focusing heavily on practical applications such as robotics.

Several cities, including Beijing and Shanghai, have set up robot industry funds worth 10 billion yuan (about 1.4 billion dollars). In January, the Peoples Bank of China announced plans for financial support of 1 trillion yuan (about 140 billion dollars) for the AI industry over the next five years.

Beyond generating positive publicity on social media, China sees humanoids as a possible answer to the challenges posed by an aging population and a shrinking workforce. A recent article in Peoples Daily, the official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, stated that robots could provide both practical and emotional support to the elderly. Humanoids could also replace workers on production lines, as the government seeks to retrain and redeploy the labor force into more technological sectors.

Yet despite the enthusiasm, a huge gap remains between humanoids tripping over a ball and those able to reliably perform everyday tasks. Safely interacting with vulnerable humans would be a far more complex achievement. The home will likely be one of the last places well see humanoid robotsfor safety reasons. Seemingly simple activities, such as handling a kitchen knife or folding laundry, in fact require extremely advanced technologies. A human hand has about 27 degrees of freedom, or independent movements in space. Teslas Optimus humanoid, one of the most sophisticated models on the market, has 22.

In China, political and public will strongly support humanoids, but for now robots remain more of an entertaining stage spectacle than a real competitor in everyday life. Still, the direction is clear: their evolution is measured not only in coordination or speed, but in the potential to transform our social and economic future.

As a famous line from I, Robot reminds us: Youre just a machine, an imitation of life. Can a robot write a symphony? Can a robot turn a blank canvas into a masterpiece? Can you? the android replied, without sarcasm. A provocation that today feels more relevant than ever.

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a masters degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.