According to critics, everyone hates artificial intelligence — no one uses it, it’s terrible, and it only produces nonsense. According to enthusiasts, it is a revolution in the world of work, everyone uses it, and those who reject it will be left behind. So, who’s right? To get some clarity — albeit in a simplified way — it is necessary to step outside the comfort zone of our own bubbles and biases and examine the available data.

I did so, and, unsurprisingly, both extremes are wrong — but let’s go in order. Most of the most reliable surveys confirm the obvious: artificial intelligence has long moved past the novelty phase and has become a regular tool for millions of people. Globally, 38% of the world’s population intentionally uses AI on a weekly basis, and a significant portion (21%) uses it daily (KPMG & University of Melbourne, Trust, attitudes and use of artificial intelligence: A global study 2025, 2025).

In 2022, 54% of employees reported using AI tools; by 2024 that number had risen to 67%. The most significant growth occurred in countries like the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, where usage went from an average of 34–37% in 2022 to 58–66% in 2024. According to employees surveyed by KPMG and the University of Melbourne, AI adoption within companies jumped from 34% in 2022 to 71% in 2024. The Stanford HAI 2025 report confirms this trend, noting that the number of companies using AI increased from 55% in 2023 to 78% in 2024.

The adoption of AI is not evenly distributed, but zigzags along generational and professional lines that already shaped the digital world. Students are, predictably, at the forefront of this trend, with adoption rates around 83%, highlighting how, for younger generations, interaction with AI is already second nature. In the workplace, AI usage is massive, though more complex: around 78% of companies reported adopting AI solutions in 2024 (up from 55% in 2023), and 58% of employees now use AI daily to optimize their workload.

Alongside increasing adoption is the growing trend of concealing AI usage—a phenomenon some call Shadow AI. Despite the technology’s ubiquity, a significant portion of workers prefers to operate in secret. It is estimated that 57% of employees admit to systematically hiding the use of AI tools from their employers (KPMG & University of Melbourne, Trust, attitudes and use of artificial intelligence: A global study 2025, 2025). This reluctance is not spread evenly across sectors but is most extreme in intellectual professions, where a striking 75% confess to relying on algorithmic support without disclosing it (KPMG & University of Melbourne, 2025). This global trend indicates that if it seems like none of your friends or colleagues uses AI—well, they might just be lying to you.

The reasons for this behavior lie in the stigma surrounding these tools and in the lack of clear corporate protocols, which leaves employees navigating uncertain regulatory waters. Silence isn’t just a way to preserve intellectual credit in the eyes of critics; it’s also a surviving strategy in professional environments that have not yet processed this technological shift. However, this practice poses a significant security problem; nearly half of users (48%) admit to uploading sensitive data of their company to public platforms, exposing organizations to vulnerabilities that remain invisible precisely due to the lack of AI usage disclosure (KPMG & University of Melbourne, Trust, attitudes and use of artificial intelligence: A global study 2025, 2025).

Despite growing usage, public attitudes toward artificial intelligence remain a mixture of contradictory emotions. Acknowledging the practical benefits hasn’t been enough to ease a deepening sense of unease. Although a slight global majority (55%) believes that the benefits of AI products and services outweigh the drawbacks,this pragmatic acceptance coexists with a growing emotional discomfort. Between 52% and 54% of individuals report that interaction with AI-based technologies makes them nervous: a significant figure that has increased by 13% in just two years, reflecting growing apprehension about the pace of change.

At the heart of this anxiety lies a profound distrust of those who control technological power. Public trust in tech companies’ ability to protect users’ personal data is steadily eroding, now standing at 47% globally. At the same time,fewer people believe these systems are fair or free from bias and discrimination. Users, it seems, are not as naïve as they are often portrayed.

Pew Research stands out from other sources in the way it measures AI reception, asking respondents to directly balance concern and enthusiasm rather than rating them as separate emotions. Globally, the data shows that concern (34%) significantly outweighs enthusiasm (16%), although a relative majority of the population (42%) is ambivalent, declaring themselves equally concerned and enthusiastic. As always, the way data is collected actively influences the outcome: while a binary survey forces a clearer stance, this one blurs opinions. In the previous survey, for example, I would have voted “more positives than negatives,” but here I would have declared myself “equally concerned and enthusiastic.”

Inevitably, concerns also extend to the socio-economic sphere, where fears of being replaced by machines remains central, albeit with evolving nuances. Sixty percent of workers expect artificial intelligence to radically transform how their jobs are performed over the next five years. However, only 36% of respondents actually fear being entirely replaced by machines. This suggests a broad awareness of the need for an evolution of human skills, even amid uncertainty over the stability of job markets and the distribution of wealth generated by automation.

Another interesting insight comes from the geographic asymmetries in how AI is received, creating a polarized global map. Cultural heritage and economic growth perspectives heavily influence how different countries approach AI.

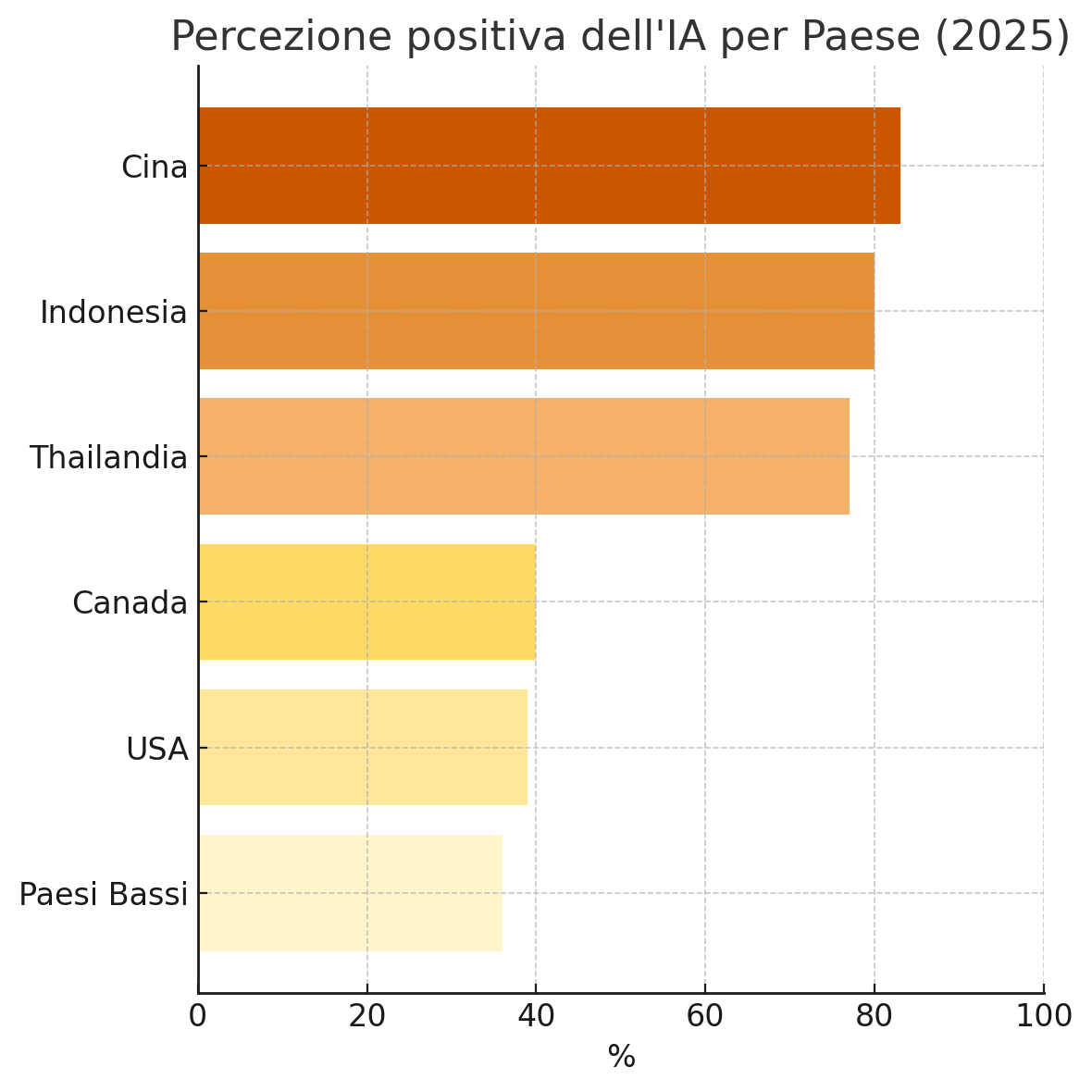

Asian nations are leading a wave of global enthusiasm that sees technological innovation as a formidable tool for collective empowerment. In China, 83% of the population believes AI offers more benefits than risks, with similarly high levels in Indonesia (80%) and Thailand (77%) (Stanford HAI, The 2025 AI Index Report: Public Opinion, 2025).

In these contexts, technology is experienced as a vehicle for social and economic mobility—capable of breaking down traditional hierarchies. Additionally, collectivist philosophies and less anthropocentric worldviews may soften the existential divide between human and machine that most concerns Western mindset.

On the other end of the spectrum, Western countries—including North America, Europe, and Oceania—show a certain cultural resistance, which is rooted in a strong emphasis on privacy and individual autonomy. In the United States, despite being home to most major AI companies—only 39% of citizens view AI’s benefits as outweighing its risks. We find similar percentages in Canada (40%), and in the Netherlands, where confidence drops to (36%) (Stanford HAI, The 2025 AI Index Report: Public Opinion, 2025). Therefore, these technologies may have been born in the West, but the East is more prepared to embrace them.

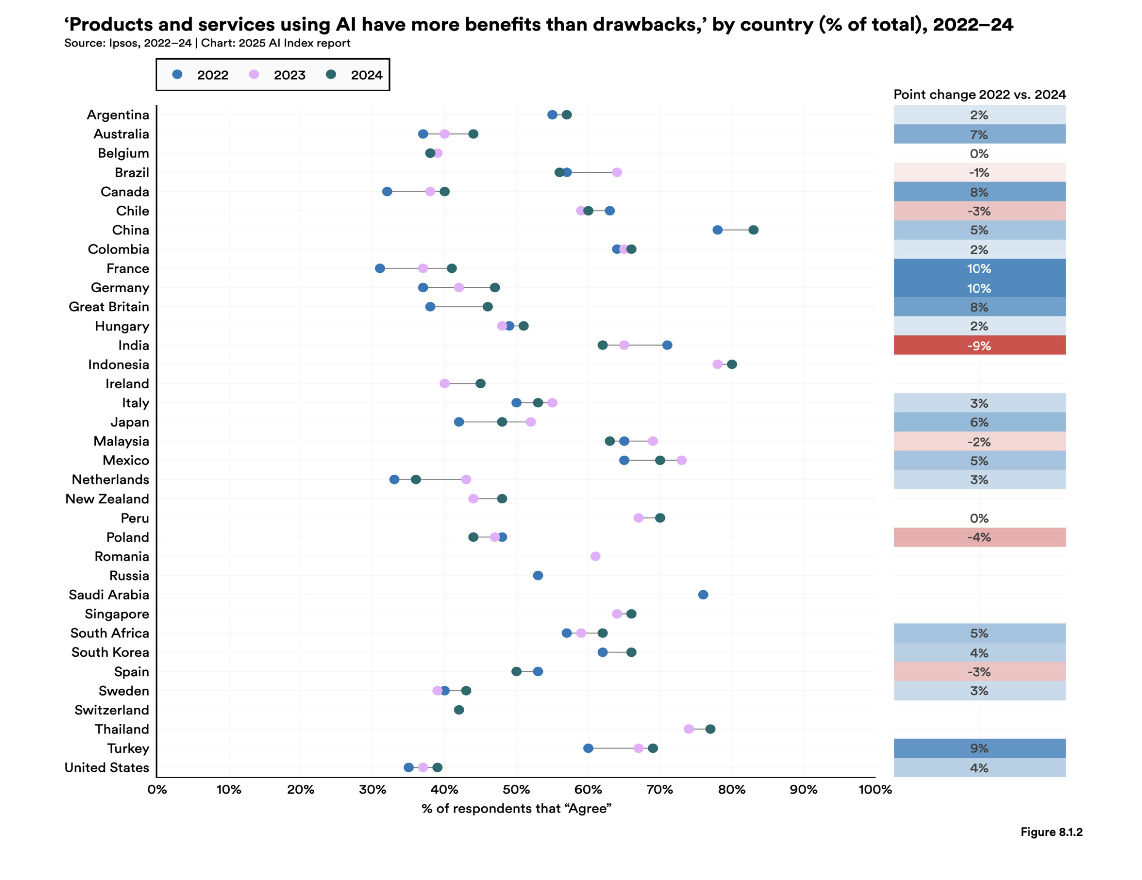

That said, even in the West, however, there is evidence of a gradual increase in trust, even in countries that were initially more skeptical. Between 2022 and 2024, trust grew by 10% in Germany and France, and by 8 % in the UK and Canada (Stanford HAI, The 2025 AI Index Report: Public Opinion, 2025).

This trend suggests that prolonged exposure to the technology is shifting fear of the unknown into a more conscious pragmatism. Where daily experience proves the tool’s usefulness, even the most cautious populations begin to acknowledge its potential, —though not without maintaining ethical vigilance over digital developments. (Stanford HAI, The 2025 AI Index Report: Public Opinion, 2025).

No extreme opinion is entirely right, as is often the case; however, it is now widely accepted that these technologies are already part of the daily lives of billions of people.

Bibliografia

Capstick, Emily. «Chapter 8: Public Opinion». In The AI Index 2025 Annual Report, a cura di Nestor Maslej et al. Stanford, CA: AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, 2025.

Fletcher, Richard, e Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. What Does the Public in Six Countries Think of Generative AI in News? Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 28 maggio 2024. https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-4zb8-cg87.

Gillespie, Nicole, Steve Lockey, Tabi Ward, Alexandria Macdade, e Gerard Hassed. Trust, Attitudes and Use of Artificial Intelligence: A Global Study 2025. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne e KPMG, 2025. https://doi.org/10.26188/28822919.

Ipsos. Global Views on AI 2024: Ipsos AI Monitor. Parigi: Ipsos, maggio 2024.

Ipsos New Zealand. Ipsos New Zealand AI Monitor 2024. Auckland: Ipsos New Zealand, giugno 2024.

Maslej, Nestor, Loredana Fattorini, Raymond Perrault, Yolanda Gil, Vanessa Parli, Njenga Kariuki, Emily Capstick, Anka Reuel, Erik Brynjolfsson, John Etchemendy, Katrina Ligett, Terah Lyons, James Manyika, Juan Carlos Niebles, Yoav Shoham, Russell Wald, Toby Walsh, Armin Hamrah, Lapo Santarlasci, Julia Betts Lotufo, Alexandra Rome, Andrew Shi, e Sukrut Oak. The AI Index 2025 Annual Report. Stanford, CA: AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI, Stanford University, aprile 2025.https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.07139.

Poushter, Jacob, Moira Fagan, e Manolo Corichi. How People Around the World View AI. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, 15 ottobre 2025.

Francesco D’Isa