In China, a team of researchers has unveiled the first bidirectional brain-computer interface (BCI) capable of learning alongside the human brain, boosting neural transmission efficiency by over a hundredfold.

Imagine waking up on an ordinary morning with a small device on your scalp that lets you reply to work emails simply by thinking, all while sipping your coffee. No, this isnt the plot of a new Black Mirror episodeits a reality already announced months ago by a team of Chinese researchers. They’ve introduced the first bidirectional brain-computer interface (BCI) capable of learning in tandem with the human brain, enhancing neural transmission efficiency by more than one hundred times.

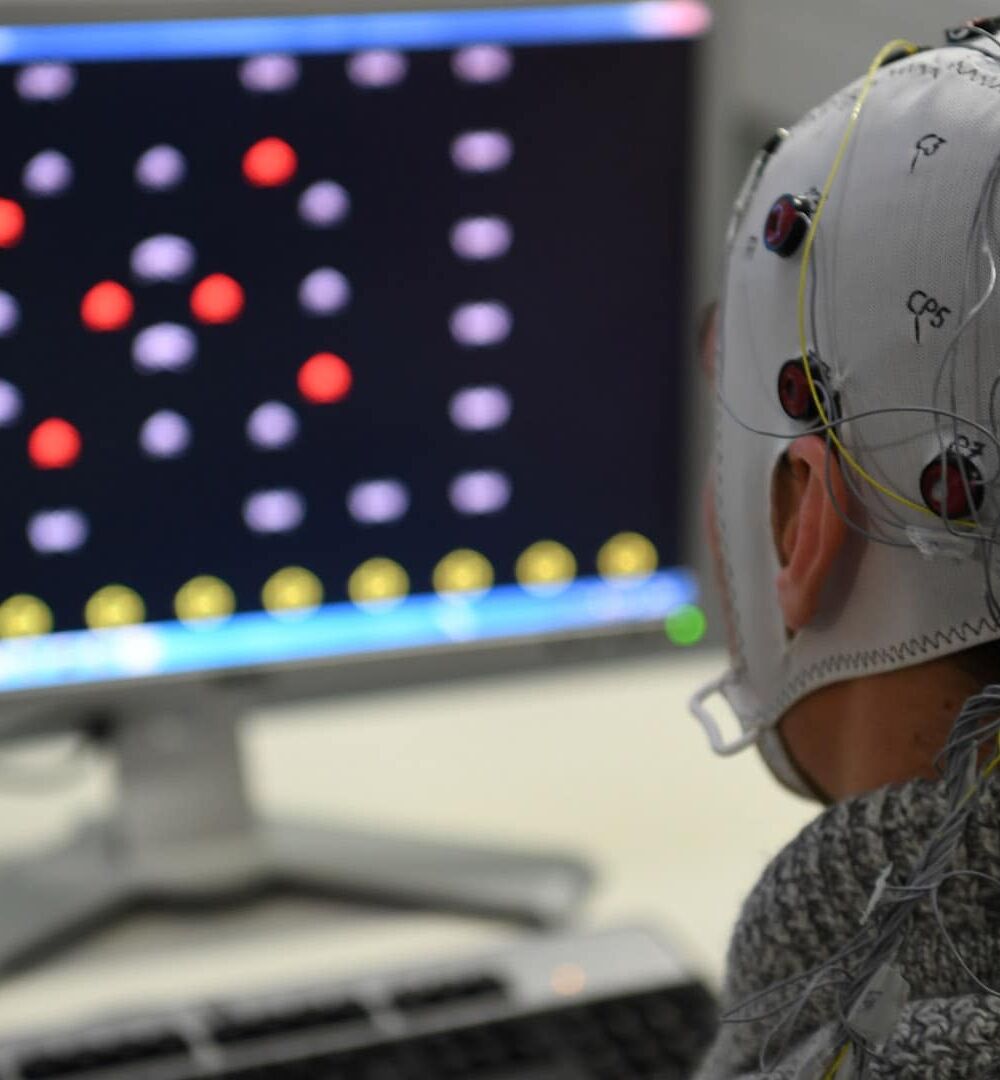

Last February, a study by Tianjin University and Tsinghua University was published in Nature Electronics, describing a BCI system that adapts in real time to brain signals. This is made possible through the use of memristorselectronic components that mimic synaptic plasticityintegrated into a decoder that evolves along with the patient. This approach surpasses traditional one-way functions where machines merely interpret thoughts without providing any real feedback. This innovation opens the door to the creation of personal, portable devices, as well as groundbreaking medical advancements in the rehabilitation of patients with brain injuries.

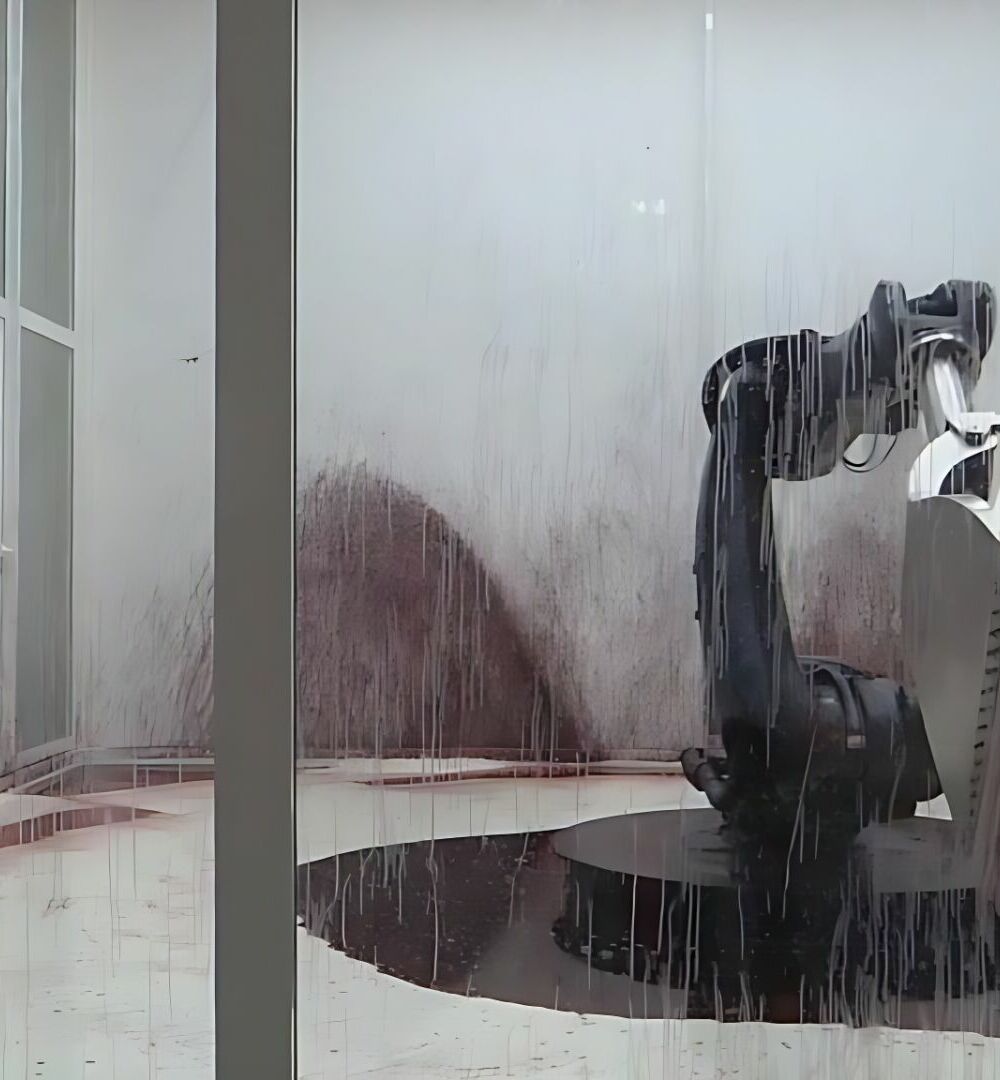

Just a few months ago, a company af filiated with the Chinese Institute for Brain Research (CIBR) announced the first three semi-flexible implants performed on paralyzed patients, with an estimated cost per procedure of around 6,552 yuan (roughly 900 USD). Thanks to these devices, patients have managed to control computers, robotic arms, and even reproduce some speech sounds. The system is semi-invasive and promises to democratize access to BCIs, previously limited to a few elite research centers. On January 5, Global Times reported a surprising result: a brain-injured patient in Shanghai “thought” the phrase 2025 Happy New Year, transmitting the message to a computer screen in real time. The implant, a flexible electronic film, recorded the intent and decoded the language with 71% accuracy across 142 Chinese syllables, with a delay of less than 100 milliseconds. In just seven days of post-op training, the patient was able to communicate again by forming more complex sentences.

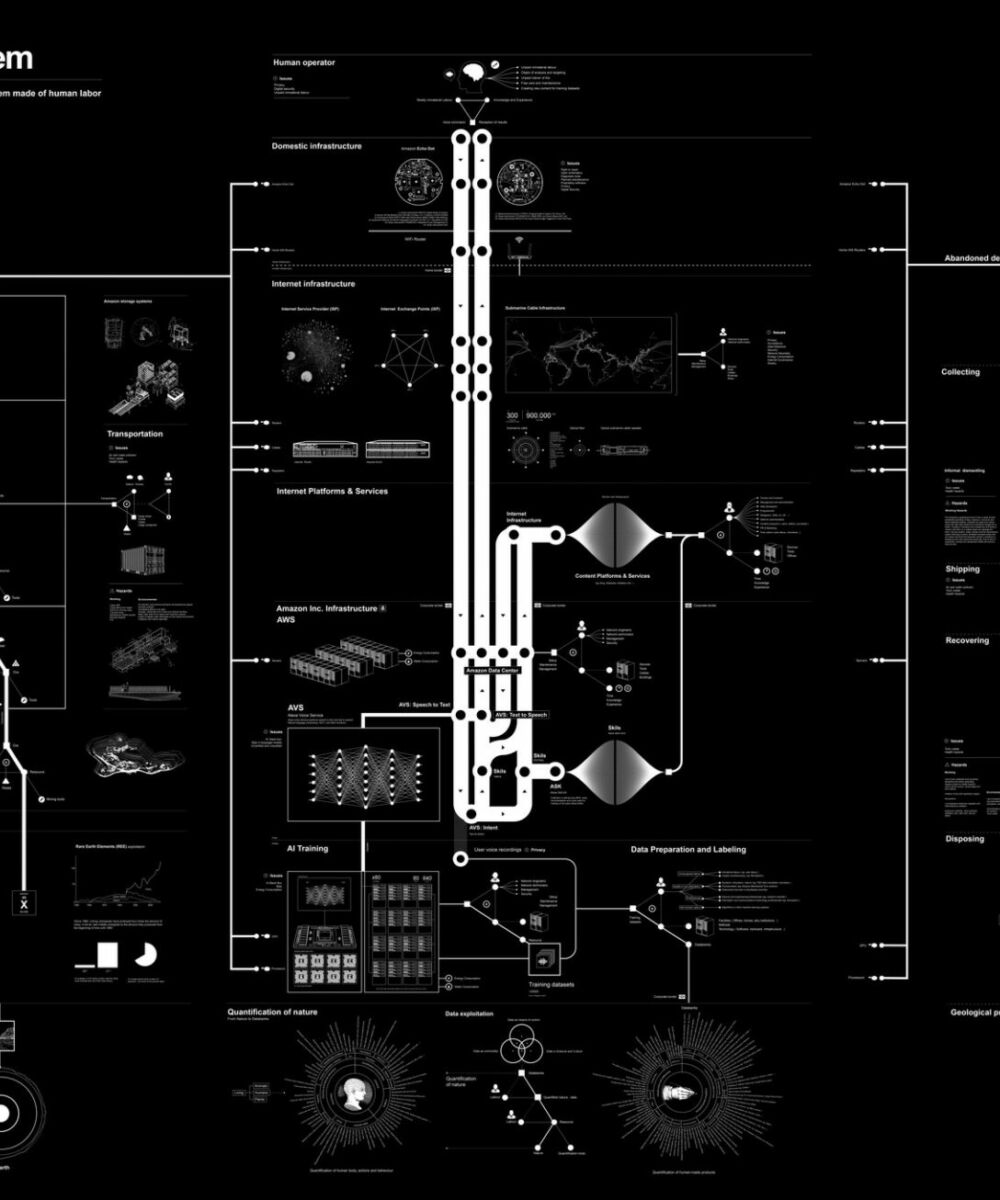

The potential applications go well beyond motor rehabilitation: think of former athletes seeking to sharpen their reaction times, professional gamers using thought as direct game commands, or executives writing reports and emails simply by focusing on key ideas. In China, the government is already developing guidelines to regulate costs, but the debate remains open on the implications of a technology that could deepen inequalities in access to what amounts to a true super-brain.

While Netflix warns us with dystopian scenarios, ethical reflection is growing in the scientific community: how human does one remain if thoughts are filtered through an algorithm? Where are the limits of cognitive enhancement? Concerns around privacy, mental sovereignty, and potential abuse of the technology are emergingranging from neuromarketing to premium subscriptions for enhanced brain functions (and yes, thats literally the plot of the first episode of the latest season of Black Mirror).

While the West still often views technological innovation as a potential threat, China is focusing on its countless advantages. The economic potential is massive: in 2024, the global BCI market was already worth $2.5 billion, with forecasts predicting a surge beyond $10 billion by 2030.

The line between organic and artificial is growing ever thinner. Unlike dystopian fiction, this is about patients regaining their voice, quadriplegics moving their hands again via robotic arms, and a universe of rehabilitative possibilities that, until recently, sounded like science fiction.

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a masters degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.