How to Queerly Hijack a Video Game

by Matteo Lupetti

LGBTQIA+ communities have historically been underrepresented in the video game industry, which still bears the legacy of that decade—from the late 1980s to the late 1990s—when the medium and the very identity of the gamer were marketed by the mainstream industry as exclusive to young, cisgender, heterosexual men (and in the West, white men).

Yet LGBTQIA+ individuals have always played video games. And ever since they’ve had the opportunity, they’ve also modified, created, and reimagined them—giving rise to a vibrant scene of queer video game détournements that reinterpret commercial works or unveil their inherent queerness.

Any video game can be treated like a toy—something that can be freely used to create infinite different games with different rules. As Bo Ruberg writes in Video Games Have Always Been Queer (NYU Press, 2019), “in the hands of the player lies the power to bring queer experience to any video game.” They continue: “Video games are a fundamentally interactive medium. They come to life not when their developers declare them complete but in the moment that players make contact with their control interfaces and step into their worlds. Between the player and the game stands a fluid space of possibility, an opening big enough for queer desires to take root and grow.” Modding—the development of unofficial modifications (mods) for commercial games—alters the toy itself. Some developers support this practice, even providing tools for mod creation. Others must be forced, hacked, sometimes with the help of unofficial software. Mods are shared freely, outside market logic, and can range from aesthetic tweaks to the main character to additional levels and even total conversions—entire new games built on the code of the original.

It’s not uncommon for mods to be created with the goal of expanding the options and content of games deemed lacking in their representation of LGBTQIA+ characters and relationships. One example is the Platonic Partners and Friendships mod for Stardew Valley (Eric “ConcernedApe” Barone, 2016), created by the NexusMods user Amaranthacyan (2021). Stardew Valley is already quite inclusive and allows same-sex relationships, but this mod enables asexual/aromantic relationships in addition to the romantic ones originally featured. Conversely, the far-right RPGHQ forum community has used modding to remove LGBTQIA+ characters from games. Modding thus becomes a battleground in the current culture wars.

Between the player and the game stands a fluid space of possibility, an opening big enough for queer desires to take root and grow

“In theory, modding makes for fantastic critical interventions. It almost transforms criticism into a science,” says Robert Yang, creator of the Radiator 1 mod trilogy (2009–2015). “For example, if I argue Doom [(id Software, 1993)] would be better if it were gayer, then I can actually mod more gayness into Doom and verify whether it’s better. With queer mods, it’s as if you can playtest your own politics. The main creative constraint of modding—that your mod will always exist in relation to its base game / industrial product—could work to your advantage, as long as you desire to be haunted like that. But just remember you’ll also be haunted by the game’s culture and community too.” Through modding, radical queer reinterpretations of the original games emerge. R.O.T. stands for Realm of Tears by Vincent Moulinet (2023), a mod for Doom II: Hell on Earth (id Software, 1994), transforms the journey of a space marine battling demons through Mars’ moons, Earth, and hell into the journey of a sex worker searching for love (or at least sex) in a gay club. The muscular bodies of Doom’s biomechanical monsters, its labyrinthine architecture, and its tension between threat and arousal are all reinterpreted in a radically queer way. “Monstrosity and body horror is a deadly anticapitalist weapon,” writes Moulinet.

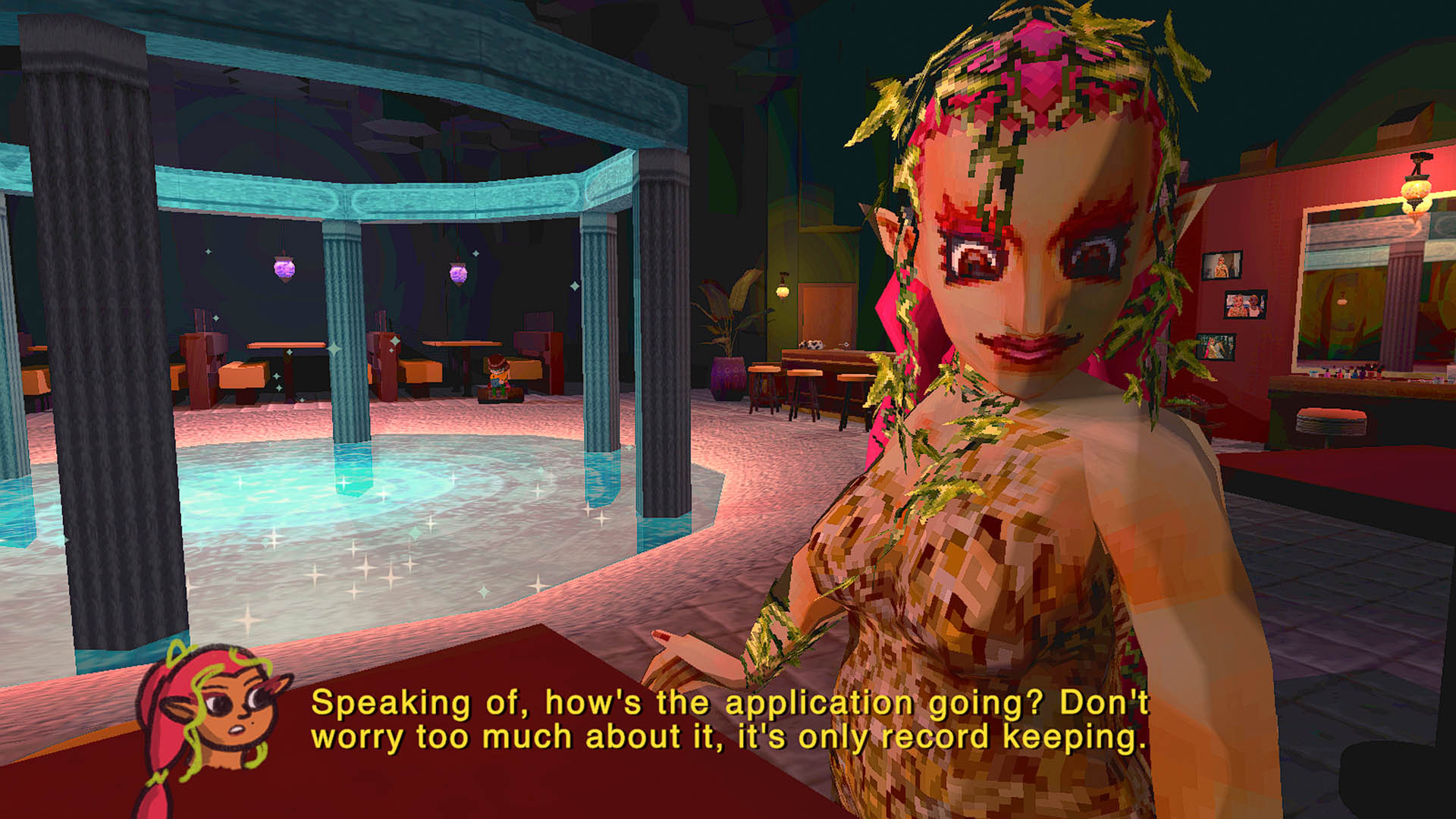

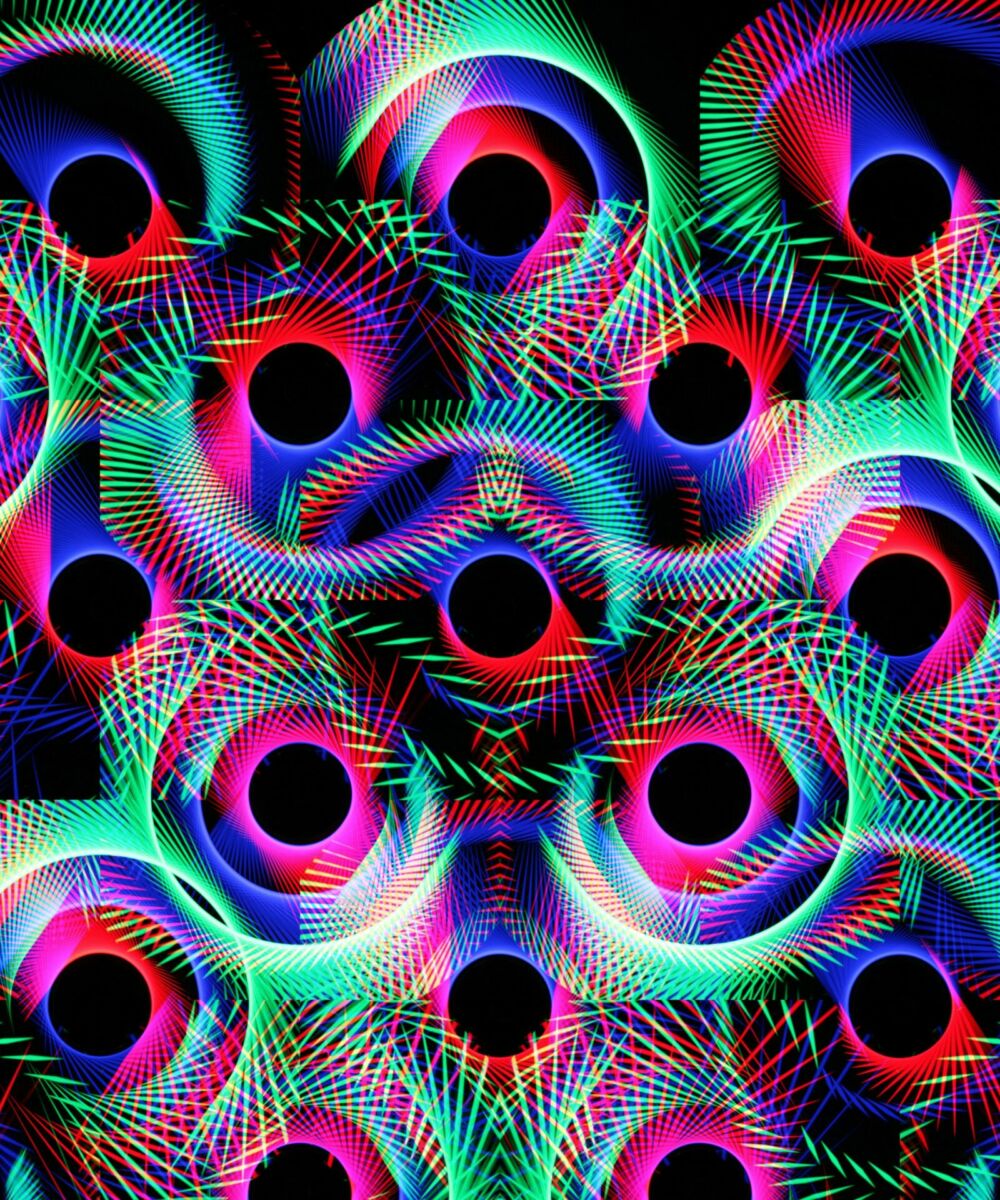

Wingless Fairies by Lily Belmira (2024) is instead a plundercore project—a video game constructed using assets from commercial works. In this case, the 3D models of the Great Fairies from Nintendo’s fantasy series The Legend of Zelda (1986–ongoing) are reused for the main characters.

Since Ocarina of Time (1998), these characters have had a visual design seemingly inspired by drag culture. In Wingless Fairies, they are no longer magical beings, but Belmira uses their bodies to tell the everyday stories of the people to whom such stereotyped portrayals refer. “I have complicated feelings about the Zelda Great Fairies,” Belmira explains. “I liked the idea of reinterpreting them as trans, but when the source material treats them as a throwaway joke, it’s less about reinterpreting and more about humanising.” Queer culture has a long tradition of reclaiming offensive representations and terms once used pejoratively—including the word “queer” itself. According to Belmira, “the way people are embarrassed or shocked or enchanted by these characters feels a lot like how people see me, or how I used to see other trans people as a kid. Making the player a fairy brings that context into the game: that androgynous character you thought was weird as a kid is you now.”

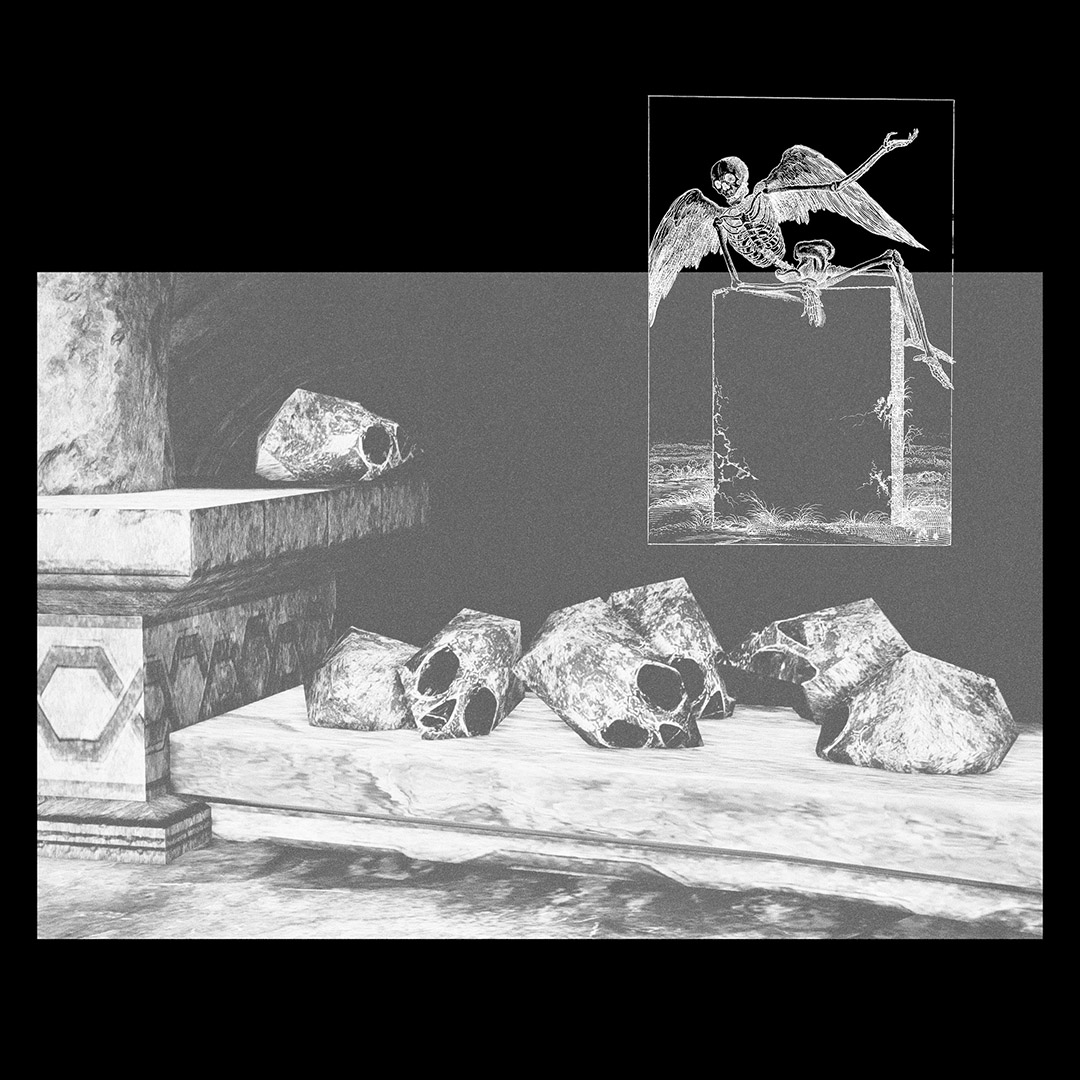

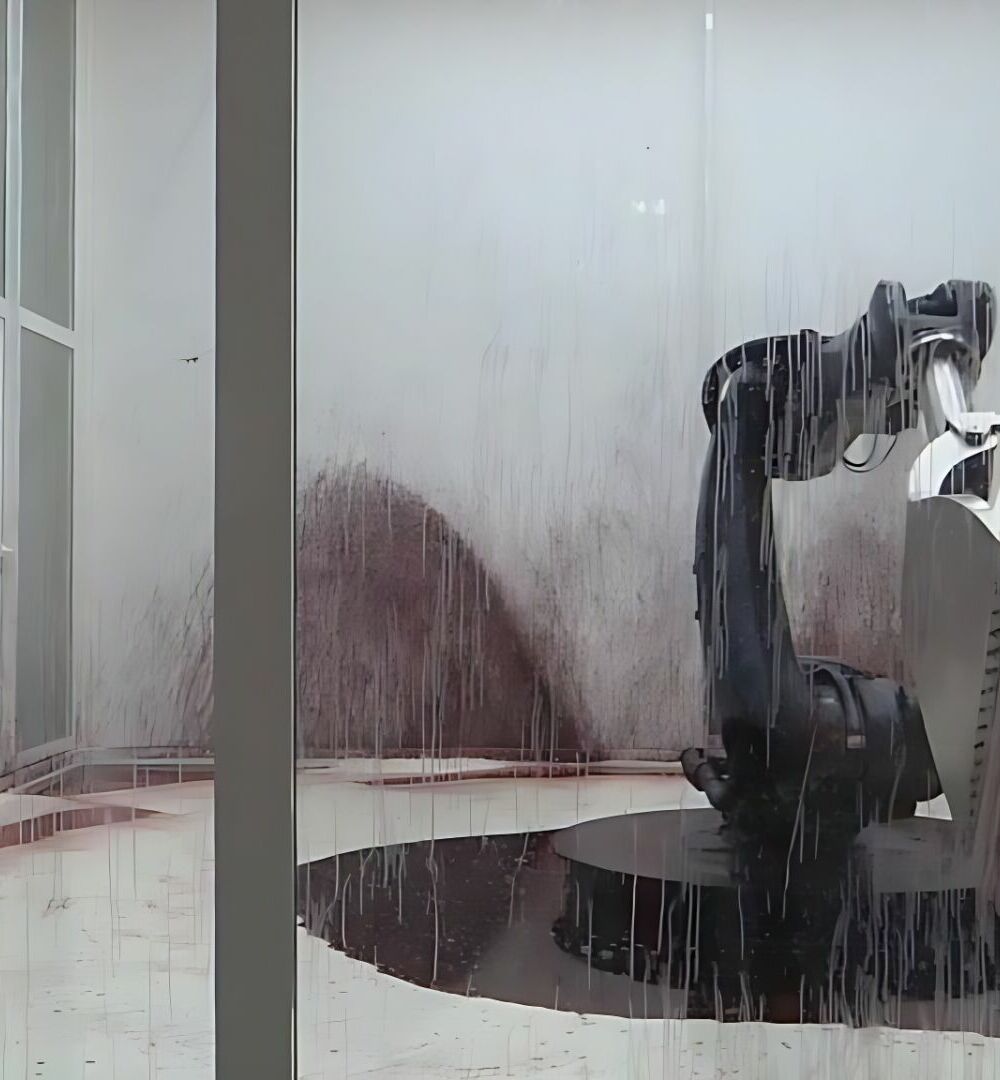

Two closely connected disciplines are machinima—cinema made within or using tools from video games—and virtual photography, the art of taking photos within video games. !CURSED! by Carson Lynn (2022) is a multimedia project focused on the figure of the reanimated skeleton. It consists of the machinima Reversal Ring and a series of collages combining digital screenshots from the dark fantasy world of Dark Souls III (FromSoftware, Bandai Namco Entertainment, 2016) with images and texts drawn from memes and archives of queer zines—often themselves made from collaged and recontextualised media. As with R.O.T., a game with a seemingly toxic hypermasculine aesthetic reveals a queer side: in the hostile, traumatic, absurd yet wondrous world of Dark Souls, queer people recognise their own experience. The skeleton—and more broadly, the undead—tells of possibilities for life beyond binaries, even the binary of life and death. “Hijacking a game can come in many forms, but the act of machinima/virtual photography often goes hand-in-hand with the exploitation of game mechanics,” says Lynn. “And that’s the most appealing part to me: creating something with tools never intended for the purpose of creation.” Lynn tends to avoid games that simplify these practices by providing tightly regulated “photo modes.” “A game company can’t regulate and censor machinima/photography/memes that exist outside of their walled gardens,” Lynn concludes.

Over the last 30 years, queer theory—developed by thinkers like Judith Butler, Sara Ahmed, and Jack Halberstam—has described queerness precisely as a deviation from normative paths, not only in terms of gender and sexuality, but more broadly. All video game détournements can be seen as queer, if we think of queerness as something that does not only mean being non-cis or non-heterosexual. Queer is challenging the imposed progression (in life as in video games), questioning what we’ve been taught to desire, and redefining what it means to win or lose—again, in both life and games. Queer is interrogating the rules of the game, and even the toy itself.

Matteo Lupetti

Matteo Lupetti writes about art criticism, digital art and video games in publications such as Artribune and Il Manifesto and abroad. He has been on the editorial board of the radical magazine menelique and the artistic direction of the reality narrations festival Cretecon. His first book is ‘UDO. Guida ai videogiochi nell’Antropocene” (Nuove Sido, Genoa, 2023), a reinterpretation of the video game medium in the age of climate change and within the new multidisciplinary paths that foreground the non-human and its agency.

![The Topologies of Zelda Triforce (Patrick LeMieux, Stephanie Boluk, 2018) [image from itchio]](https://www.the-bunker.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/The-Topologies-of-Zelda-Triforce-Patrick-LeMieux-Stephanie-Boluk-2018-image-from-itchio-thegem-product-justified-square-double-page-l.jpg)