Programmed, Kinetic, Generative Art. Story of a long voyage

by Claudio Francesconi

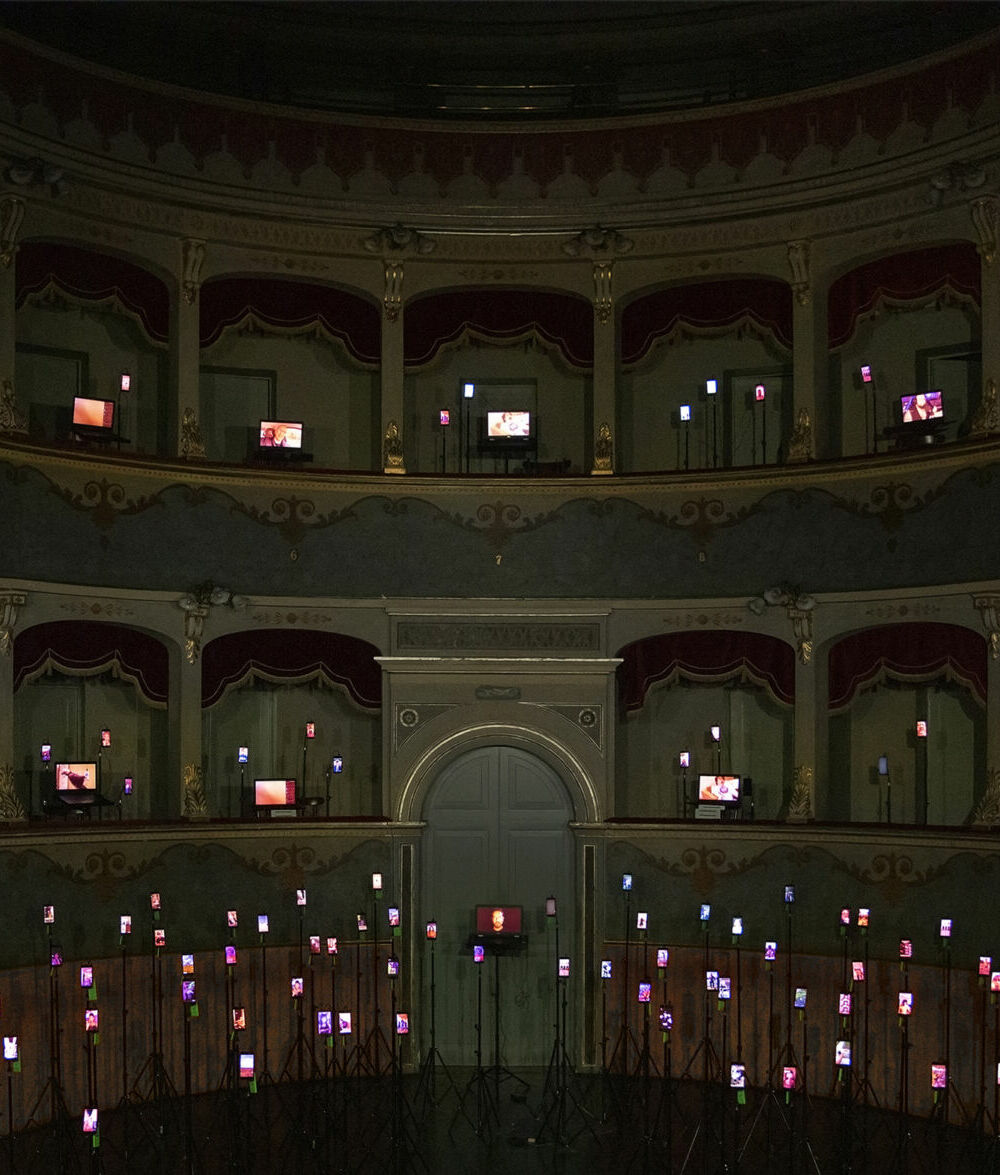

Imagine finding yourself in Italy in the Sixties. The country was growing at record rates, the economy was booming, industry performing more brilliantly than ever. Italian brands had conquered the world, and everyone raved over the beauty of goods “Made in Italy”. Those were the years of the “La Dolce Vita” as depicted by Federico Fellini with Marcello Mastroianni, the years when the Vespa became a symbol of freedom, when Olivetti effectively invented the first domestic adding machines, long before the arrival of the personal computers. Indeed, it was at the Olivetti store in Milan, in the splendid Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, that the first show of kinetic and programmed art was held, curated by Bruno Munari and Giorgio Soavi. In a world where the art we were used to was figurative, or at the most, representative of one or more of the conceptual vanguards that were rapidly developing, this exhibition of programmed art aroused tremendous curiosity. Between the appreciation of some critics and the scorn of many others, what people saw in this new and exciting context was a new and revolutionary concept of the work of art: “the open work”.

The concept of “open work “, theorized by Umberto Eco in his essay of the same title, published in 1962, is fundamental for an understanding of kinetic and programmed art. Eco defined the open work as a work of art that is not definitively completed, but that requires the interaction of the viewers to be complete. This concept perfectly describes the intentions of the kinetic and programmed artists, who designed works that could evolve in time and respond to external stimuli. At the great Olivetti exhibition, these concepts seemed to create a new form of interaction with the visitors who, fascinated, lingered over the works of Boriani, Costa, Biasi, Colombo, etc.

The artists in question were from groups that at that time had begun forming in the cities of Padua and Milan, in particular the Gruppo T and the Gruppo N, but also the Gruppo MID, one of whose members – Antonio Barrese – is still active in the kinetic field.

The new conception of the work thus marked the change of a paradigm that had been, in some ways, unalterable for centuries: the sacredness of the work-viewer dynamic was violated, and between the two a flowing interaction was born, a perceptive dance of the process of experiencing creativity. Color, shape and space became subjective variables in the experiential context, and the works were fresh and inviting as never before.

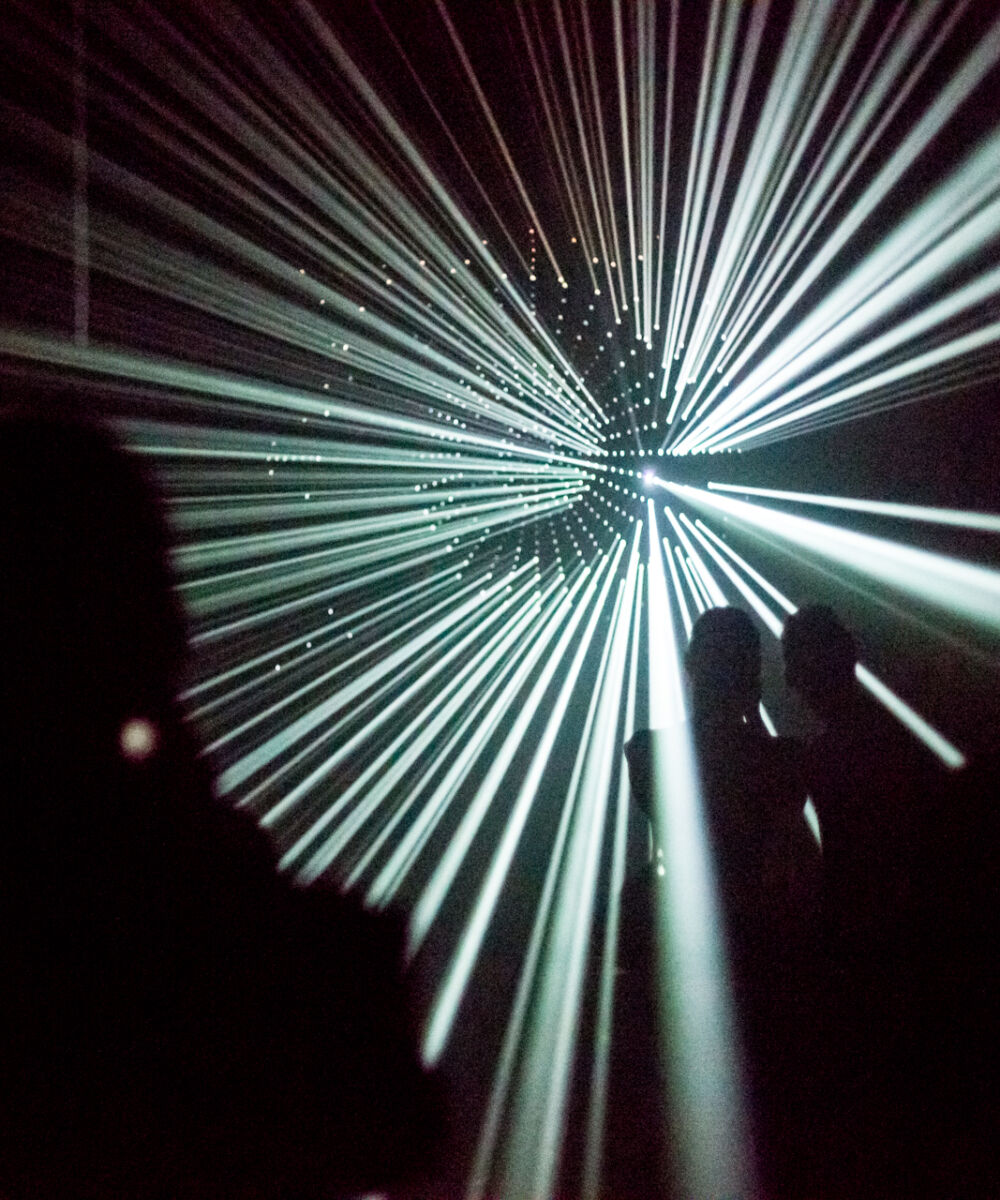

Everywhere one looked, the world was awakening from the tragedy and hardship that the two world wars had produced. Nevertheless, the terrible scars and memories of their aftermath had created a powerful desire for rebirth and a great enthusiasm toward science, which was making exciting breakthroughs, opening extraordinary new horizons. Technology, for the first time in human history was becoming a part of ordinary people’s everyday lives and, little by little, changing society, along with the ways people lived. It is understandable how, in a world where television was slowly finding a place in every home, art too would be affected by this wind of change, and artists were increasingly attracted to the idea of experimentation, exploring what the new technologies had to offer them.

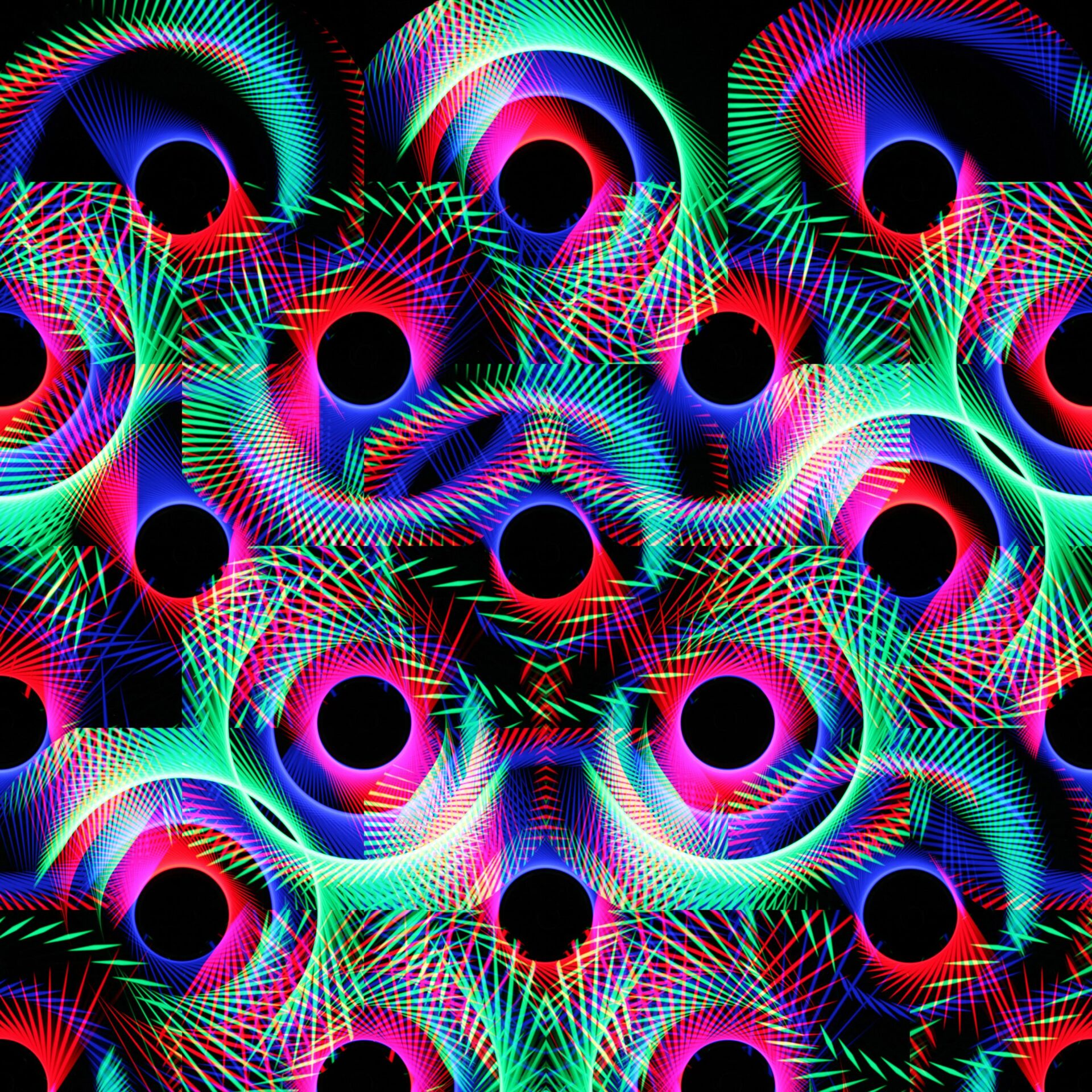

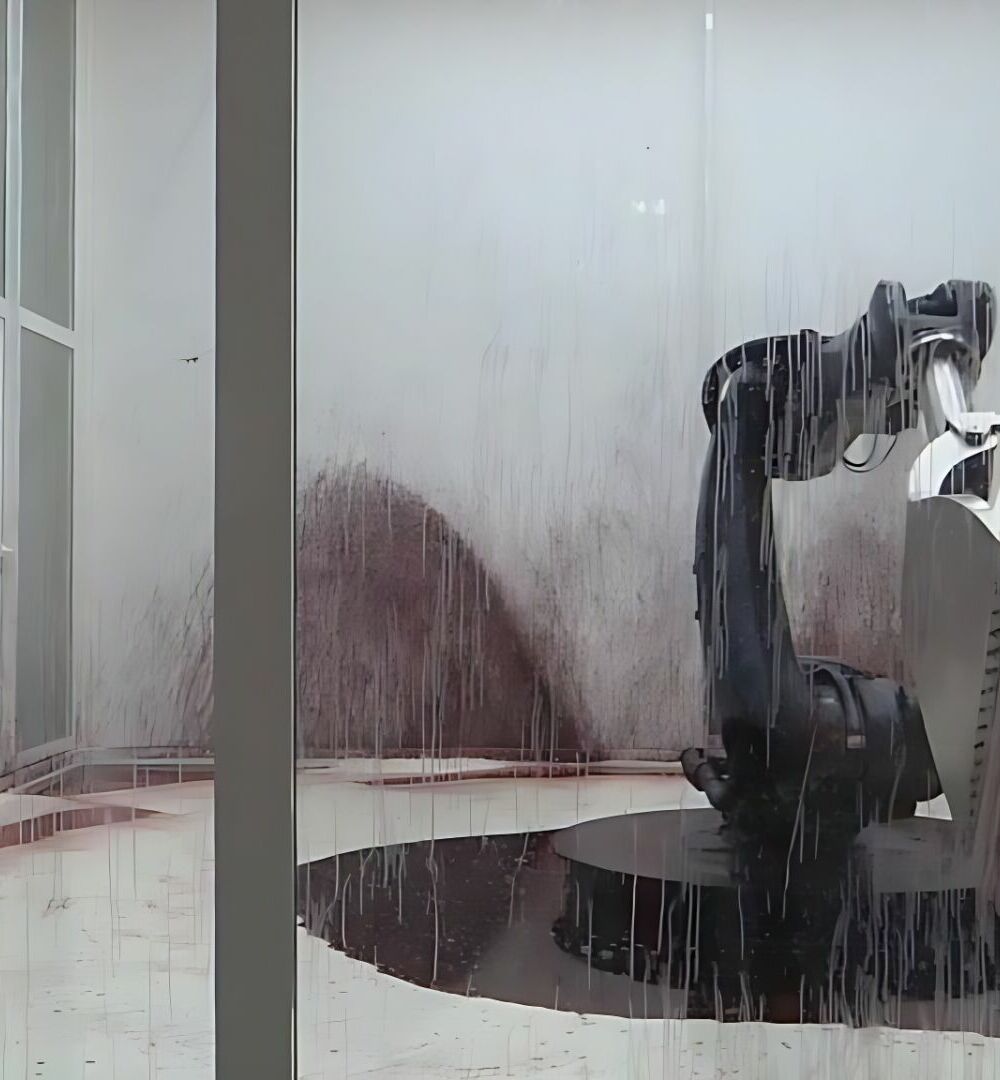

In those same years, in the meantime, somewhere in the world, someone had the absurd and shocking idea of turning the creative process on its head. Until then it had always been a human activity, from painting to sculpture, from collage to performance, human artists had always been the creators of the work of art as it was known until that time…until the first forms of generative art appeared. The idea was that the work of art could grow out of the action of a machine, such that the creative process became substantially an automatic act, in which man had no role, other than that of preparing the machine to produce the creation. The first forms of generative art were linked more than anything else to commonly used scientific machinery and, for that reason, the first generative artists came from the world of science and the laboratory.

Art and science, which for long centuries have fought each other, had finally arrived at an agreeable sort of marriage; creative and emotional humanity was wedded to the rational, calculating machine and the child born of this union was a completely new form of art in which man was not the sole, unquestioned protagonist but had to divide the glory with the technological element, the machine.

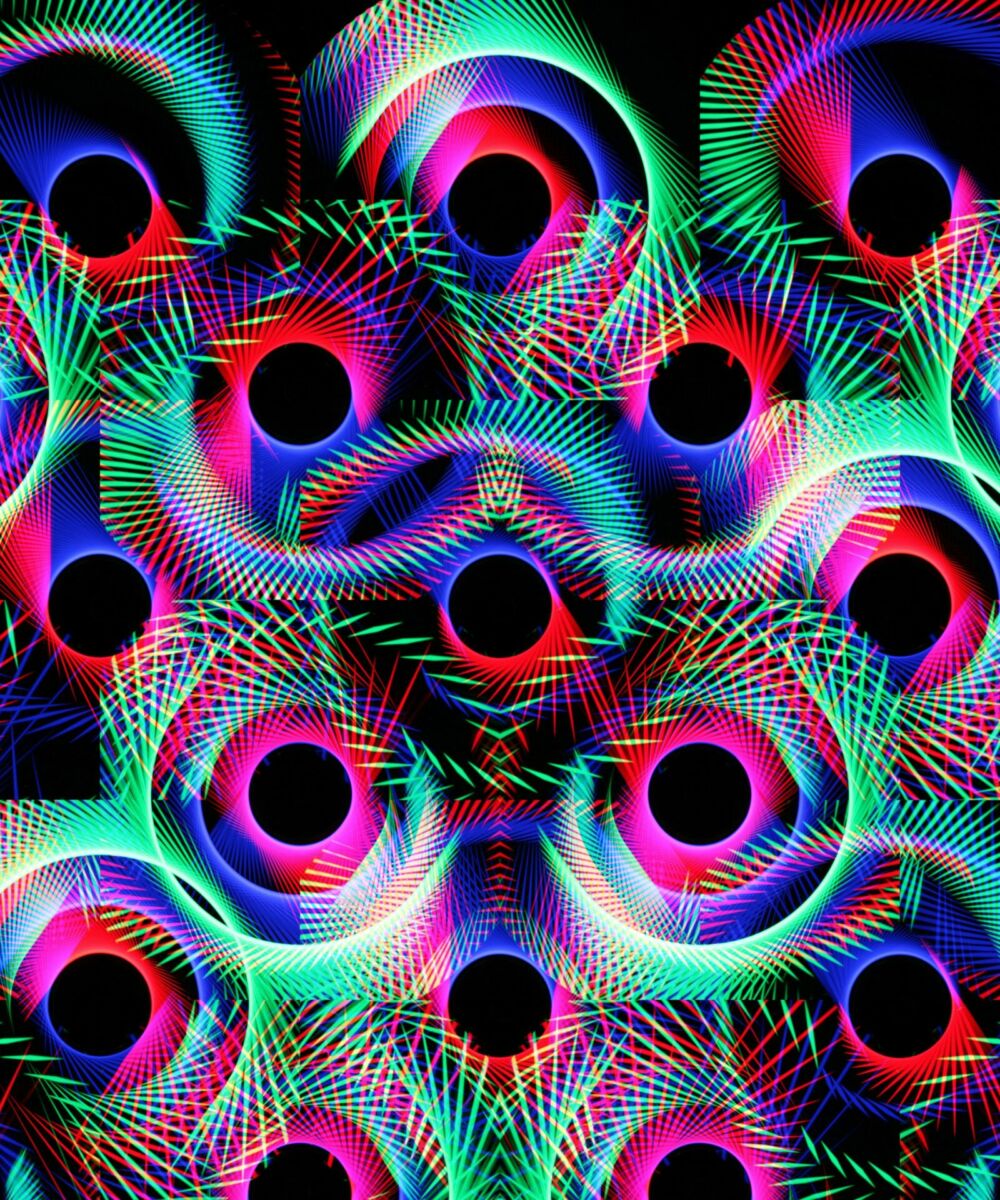

Obviously, the Sixties were very important also for the discovery of a great number of tools that, from then on, would become more and more central to the history and life of humankind. With electronics came the computer, which created a new and violent wave of technological development that, as we can easily see, had a significant impact on every aspect of daily life and, unexpectedly, also influenced the art world by introducing new and interesting paths of generative art in which artists used computers to produce works. From that time on, the protagonists were what we now know as algorithms.

Anyone enthusiastic about both art and technology was probably aware of the first experiments in computer art. The first name that comes to mind is that of the extraordinary Hungarian artist, Vera Molnar, considered the first true computer-artist in history. Obviously, this type of experimentation, which certainly won’t be remembered for its expressive force or its lyrical impact, did not arouse enthusiasm at the time, but immediately drew attention to the changes and to the advent of the pioneers in these new disciplines.

Time passed, and technology gradually became more flexible, malleable, and increasingly user friendly. If initially using these machines was effectively complex and required access to laboratories and research centers, with time they became familiar, as well as more economical. The electrical circuits became electronic circuits, computers were programmed, and the first hard disks arrived. The algorithms generated by the artists became increasingly complex and their visual output more acceptable.

In telling about this period, which only lasted a few short decades, in which technological development became possibly the central element for understanding the changes that have taken place in society, it seems almost natural to observe how much art was, in turn, influenced by these tremendous changes. Kinetic/programmed and generative art were two sides of the same coin, parallel images of a world that more than ever saw man at the center of the universe, a sort of new technological renaissance that burst with arrogance and self-awareness into the search for new forms of intellectual lyricism and creative storytelling, mankind and code having undertaken the voyage together.

The two art forms had many elements in common. We are thinking, for example, of the dynamism, both in generative art and in programmed art, as well as, obviously and above all, in kinetic art: the work loses the immanence to which we had been bound until then. Focusing on the use of technology, both movements make intensive use of the technology available in their time. Kinetic art exploits physical mechanisms and motors, while generative art uses circuits, algorithms, and software in its most recent iterations.

A human being programs the machine that programs the tool that produces the work so we might say that man is the creator of the creator and thus a creator of artists.

The most recent developments in art and technology have led to the birth of another art form linked to information technology: digital art. With the advent of the blockchain and of NFT (Non-Fungible Tokens), digital art has reached a new stage of evolution. NFTs make it possible to create unique, verifiable works of art that can be exchanged on decentralized platforms. This development has led to a democratization of art, allowing artists to sell their works directly to collectors without intermediaries. NFTs have found a perfect synergism with generative art. Artists like Tyler Hobbs have used algorithms to create unique works of art, registered as NFTs on the blockchain. This approach makes it possible to combine the uniqueness and variability of generative art with the traceability and ownership guaranteed by the blockchain technology.

If we look at the process, we can trace an ideal line connecting the first experiments in kinetic art and all the development that has taken place in art since then, linked to the technical world and to technology. Digital art is the most recent and perhaps the most extreme example, but the approach is basically the same, as is the idea underlying this long voyage: art is dynamic and changeable, linked to the laws of perception of our everyday life. Art is a shadow of mystery that runs through the hidden codes of the physical laws that govern the world around us, in the orbit of an atom, in the short, rapid voyage of a photon, in the molecule of silica, the primary element of digital substance.

Obviously, what we are experiencing today, with the advent of the new AI (Artificial Intelligence) technologies, is really an exasperation of the concepts that we have just examined, to the extent that we question whether it even makes sense any longer to speak of art when a work is produced by a machine. Indeed, the creative capacity of algorithms is truly disconcerting, and the creative process is moving farther and farther away from mere imitation of what human artists have already produced. A human being programs the machine that programs the tool that produces the work so we might say that man is the creator of the creator and thus a creator of artists.

In conclusion, viewing at this point the entire voyage from the standpoint of those who live art and experience it as spectators, we can say that the undefinable quality of the work of art has an appealing counterpart in the surprise and amazement at humanity’s wonderful ability to find and create new forms of art in every epoch. From the time when a primitive human being, exhausted after a day of hunting, first plucked the strings of his bow, dozing in front of the fire, and produced music, to most extreme and dematerialized forms of creativity represented by algorithms created by algorithms instructed by creative programmers, humanity has always been the primary catalyst, the intelligent inventor of the world’s codes.

CLAUDIO FRANCESCONI

After studying software engineering, he began working in the field of advertising and film graphics as a post-production and special effects operator, collaborating with important projects in London.

Alongside his professional career in multimedia and data science, in 2006 he opened his first art gallery, Gestalt Gallery, in Pietrasanta. Over the course of more than 10 years, the gallery hosted several successful exhibitions in both gallery and public spaces, featuring renowned masters as well as launching emerging artists with great success and media visibility.

In 2017, Gestalt Gallery transformed into Futura Art Gallery, embarking on a more ambitious artistic journey focusing on historical art within minimalist, kinetic, and geometric genres, alongside exhibitions by emerging contemporary artists.From 2017 to 2020, he served as the representative of art gallerists in the Pietrasanta area within the National Association of Galleries (ANGAMC).

In 2020, he became head of digital for the magazine ARTEiN, which later became AW ArtMag.Since 2021, he has been involved in NFT and Cryptoart, creating the largest Italian NFT community on Facebook (NFT Italia), which later expanded to other social media platforms.Since 2022, he has been the Head of the NFT and Digital Asset Department at Pandolfini Auction House, the biggest and the oldest auction house in Italy. He is currently organizing the second NFT auction. The NFT department at Pandolfini is the first of its kind in Italy.In 2022, he was invited to testify before the Cultural Commission of the Chamber of Deputies as an expert in the NFT art sector to discuss related issues.

Since 2022, he has been the Chief Curator of the artistic collective Bottega, which brings together several dozen high-level Italian NFT artists.

![The Topologies of Zelda Triforce (Patrick LeMieux, Stephanie Boluk, 2018) [image from itchio]](https://www.the-bunker.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/The-Topologies-of-Zelda-Triforce-Patrick-LeMieux-Stephanie-Boluk-2018-image-from-itchio-thegem-product-justified-square-double-page-l.jpg)