An incarnation of my hatred shall ever follow your kind, dooming them to wander a blood-soaked sea of darkness for all time! says the demon king Demise in the finale of The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword by Nintendo (2011), currently the first video game in the complex internal chronology of the fantasy series The Legend of Zelda (1986ongoing). It is the curse that begins the cycle of violence and destruction that defines the saga. In The Legend of Zelda, the incarnation of Demises hatred, Ganondorf, clashes across different eras and thousands of years with the reincarnations of the protagonist Link and the various Princess Zeldasdescendants of an original Zelda, herself a reincarnation of the goddess Hylia, to whom three creator deities entrusted the kingdom of Hyrule. And, most importantly, to whom they entrusted their power, encapsulated in the three shards of the magical Triforce that Demise first and Ganondorf later try to seize.

Even the original The Legend of Zelda (1986) sets us up to explore a Hyrule already destroyed by Ganon (the demonic form of Ganondorf), a land where cities no longer exist and people hide in underground caves while monsters roam the surface. Even when Link manages to save the kingdom, after nearly forty years of entries in the series, we now know that the victory will only ever be temporary and that the world will soon be devastated againsometimes almost immediately after the events of the previous game, as seen in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (2023), the sequel to The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). As noted by Gerry Canavan (“The Legend of Zelda in the Anthropocene”, in English Faculty Research and Publications, 2019), Hyrule is trapped in this cycle primarily by the commercial needs of capitalist production and consumption: the Japanese multinational Nintendo must continually place the game world in danger in order to keep developing new episodes featuring a cast of always recognizable characters. But this relentless return of the past also invites a reading through the lens of hauntology.

The term hauntology is a portmanteau of hanté (haunted, possessed, obsessed) and ontologie (ontology), coined by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in Spectres de Marx (Routledge, 1994), a work that originated as a series of lectures at the University of California. For Derrida, after the fall of the Soviet Union and what Francis Fukuyama called the “end of history” and the apparent final victory of capitalism, the ghost of Karl Marx continues to haunt the worldjust as the ghost of communism haunted Europe in the opening lines of Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto (1848). This specter continues to reveal the cruelty of capitalism and, in doing so, inspires alternative futures. Hauntology, usually written in English, is thus an anti-ontology that studies not what is, but what is notor rather, what both is and is not, like ghosts. What no longer is, or what is not yet, and yet still affects the presenthaunting it. Hauntology is a framework for interpreting reality that focuses on what has been left out: an ontology of what has been repressed, which returns in spectral form, as a compulsion to repeat a buried trauma.

There are also design reasons why video games, perhaps more than other media, invite hauntological thinking, said Stefano Caselli, author of A Phantom World. For a Hauntology of Breath of the Wild in The Legend of Zelda. Aesthetics, Morphologies and Representations of an Endless Cycle (edited by Luca Papale, Ledizioni, 2024). When we spatialize narrative, as happens in a video game, we remove the narrative from time and place it in space. Game design is all cartographythats why video games are full of post-apocalyptic narratives that tell the past through space. Moreover, in a video game, the player is an agent who doesnt belong to the game world. Your very ability to act in the game is ghostly.

The entire main character triad of The Legend of Zelda is haunted by the past, forced into predetermined roles for millennia, and lives in a world of ruinsof Hyrules past and the series’ past, through references and callbacks. But it is Ganondorf who is the true ghost. Starting with The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998), Ganondorf is often foretold or accompanied by his ghosts, as though even in life he were already deador already a ghost himself. Because in The Legend of Zelda, Ganondorf is the great repressed, the unspeakable. The only man among the Gerudo, a people forced to live in a deathly desert while Princess Zeldas kingdom enjoys the grassy pastures of Hyrule. A people of only women, dark-skinned thieves whose costumes are inspired by Middle Eastern dressa characterization that, within the sexist and racist imaginary underpinning The Legend of Zelda, defines the Gerudo as savage, primitive, inhuman. A non-culture. When the Triforce is shattered into its three parts in Ocarina of Time (and remains broken in later titles, even further divided in some), Link receives the shard of Courage, Zelda that of Wisdom, but Ganondorf is given the shard of Power. The so-called civil worldthe world of Link and Zeldawants to erase and forget Ganondorfs almost primordial (and demonic) violence, yet that violence is itself part of the worlds balance, and is therefore fated to return.

Demonsespecially those from Japanese culturemove between the visible and the invisible, between past and present; they represent not only the dead, but also that which was never realizedor is yet to be realized, writes Diletta Coppi in issue 28 of Charta Sporca, dedicated to Ghosts. They are the shadow of what has been discarded, repressed, forgotten. In a world imagined as fully realized, one that seeks to reduce all resistance to mere conformist whims, ghosts are the last ‘real’ symbols of what refuses to be absorbed into the system structuring our perception of reality. Traces, resistances, remnants of what dominant discourses cannot digest (italics in the original).

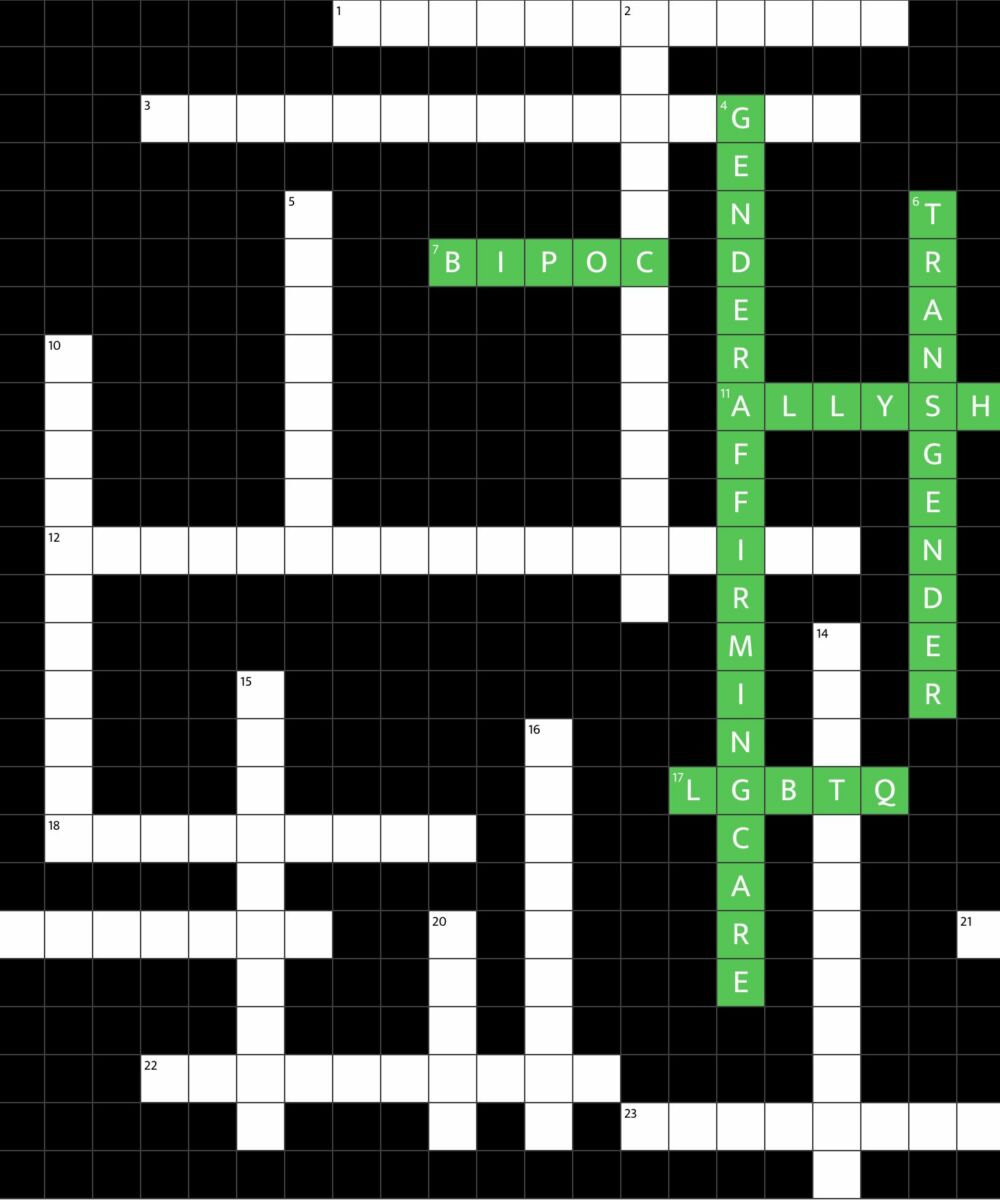

Ganondorfs cyclical return is used by JohnLee Cooper to narrate the cyclical return of fascism in Decomposing Corpse of Ganondorf. A piece of plundercorea video game created using elements taken from other video games and, in this case, from the internet. Assets conjured from the past to haunt. The game was developed for the Paradise Blitz Jam 8 event, themed around the palimpsesta text that has been erased to reuse its medium, yet usually retains a trace, a ghost. In Decomposing Corpse of Ganondorf, you are a swarm of flies that grows by devouring the corpsesthe 3D modelsof various Ganondorfs from the Zelda series, scattered among the skyscrapers of a city pulled from the Fourside setting in Super Smash Bros. Melee (HAL Laboratory, Intelligent Systems, Nintendo, 2001). At the center of the scene, however, are also two texts, including a reproduction of the English Wikipedia paragraph describing the public display of Benito Mussolinis corpse in Piazzale Loreto in 1945. Ganondorf seemed like an apt metaphor for this 2020s recurrence of fascism that we’re seeing everywhere Cooper told us.

In my country today there are some who say that the War of Liberation was a tragic period of division, and that all we need is national reconciliation, said Umberto Eco in his 1995 lecture at Columbia University, later published as Eternal Fascism (Ur-Fascism, published on The New York Review of Books). The memory of those terrible years should be repressed, refoulée, verdrängt. But Verdrängung causes neurosis. And Eco went on: [… E]ven though political regimes can be overthrown, and ideologies can be criticized and disowned, behind a regime and its ideology there is always a way of thinking and feeling, a group of cultural habits, of obscure instincts and unfathomable drives. Is there still another ghost stalking Europe (not to speak of other parts of the world)?

Matteo Lupetti writes about art criticism, digital art and video games in publications such as Artribune and Il Manifesto and abroad. He has been on the editorial board of the radical magazine menelique and the artistic direction of the reality narrations festival Cretecon. His first book is UDO. Guida ai videogiochi nellAntropocene (Nuove Sido, Genoa, 2023), a reinterpretation of the video game medium in the age of climate change and within the new multidisciplinary paths that foreground the non-human and its agency.