The great deception of the technological revolutions

By Alessandro Mancini

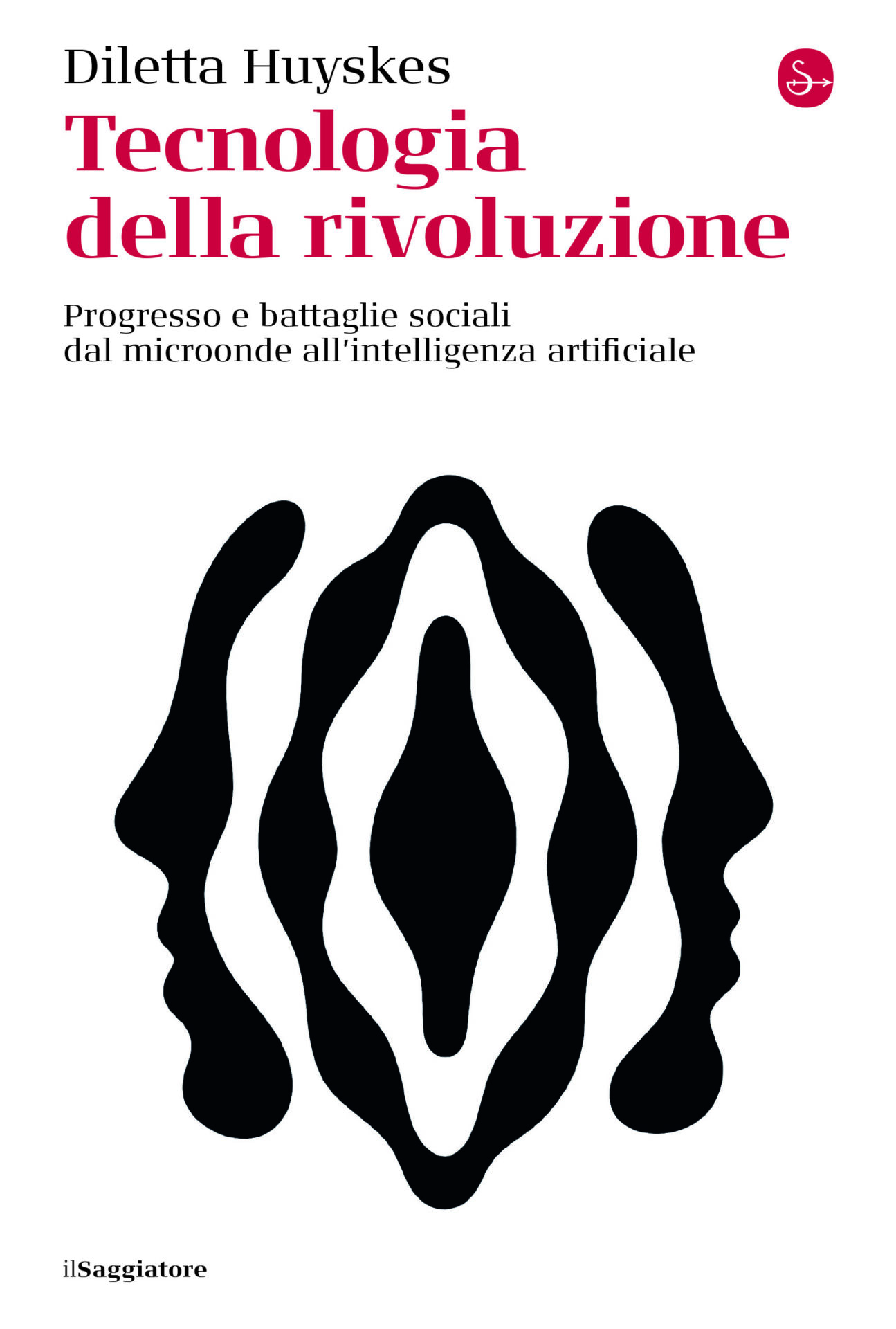

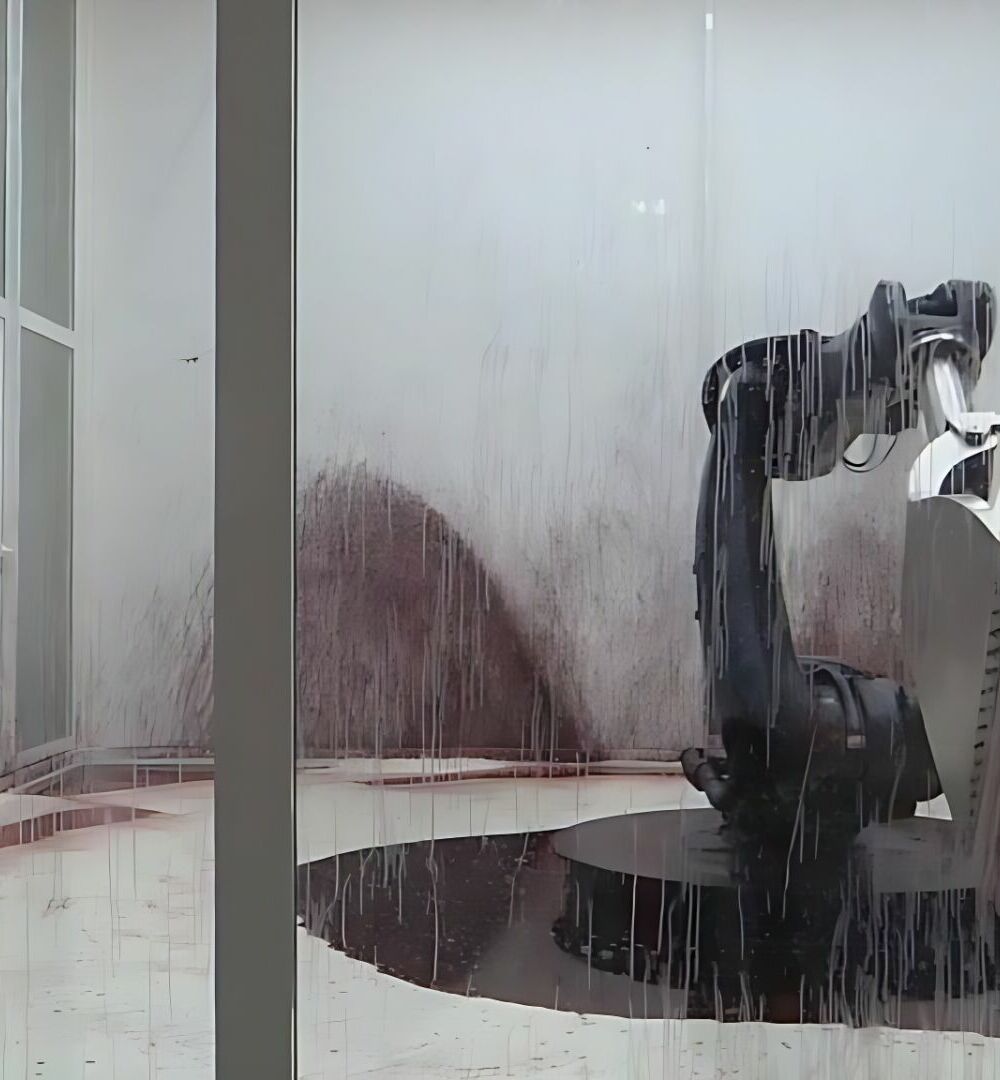

Every new technology brings with it the promise of a technological revolution, but quite often, this promise is not kept. Indeed, rather than generating progress, advances in technology may actually increase inequality, by giving certain social groups even more advantages over other, already disadvantaged groups. Diletta Huyskes turns a spotlight on the paradoxes that the introduction of new technology gives rise to in a volume entitled Technology of the Revolution, published by “il Saggiatore”. Diletta Huyskes is a research professor who studies the ethics of technology and the social impacts of artificial intelligence. She is co-CEO and co-founder of Immanence, a beneficial company for responsible technology and artificial intelligence.

Tracing back through the history of technology, from the bicycle to artificial intelligence, from microwaves to birth control pills, the author shows her readers how, behind every new invention, there are always precise human choices that, in some cases, may lead to social exclusion. Thanks to the rediscovery of the many contributions made by women between the Sixties and the turn of the millennium, Technology of the Revolution forces the readers to reflect on the impacts that these innovations have had on the collectivity, and on how to ensure that technological revolutions do not lead to social involutions.

The word “revolution” is at the center of your analysis, right from the title of your book. Every new technology does indeed bring with it the promise of revolutionizing the current state of things. Is that always true or does it sometimes instead (or simultaneously) cause an involution, or at least leave behind some already disadvantaged groups, like minorities?

The idea of revolution is the focal point that, in my opinion, best describes the relationship between technology and discrimination or exclusion. Usually every innovation – right now it’s Generative AI, for example – is presented to the public as a revolution but with a different meaning from that which people ordinarily give the word. People think of revolutions as being political and social in nature, with subversive and paradigmatic outcomes. Technological revolutions are generally detached from social revolutions and quite often, indeed, a technological revolution does not bring about any sort of automatic social progress. Take the cases of Omar and Sara, for example: two Dutch citizens who were victims – in different ways – of systems of artificial intelligence used for predictive purposes between 2014 and 2021 by several municipalities and also by the central government, jointly with the Dutch fiscal authorities, for the purpose of assigning a level of risk to every individual applying for public welfare, or to classify persons at high risk of becoming criminals in the future.

Going back in time, the bridge built by the architect Robert Moses between the Thirties and the Forties in New York, which connected Manhattan to Long Island by car, if viewed as technological infrastructure, is an example, as explained by the political historian Langdon Winner in “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” (1980), of how technology can, on the one hand, make something new possible – reaching the island by car – and on the other, can automatically exclude entire social groups such as those who travel on public transport, consisting largely of poor or black people. According to Winner, a specific form if discrimination would thus have influenced the social construction of those bridges, as in many other cases of urban planning. All technological revolutions, from those inherent to the sexual sphere to those regarding domestic life, despite the promises, have benefited certain already privileged categories of individuals, excluding, effectively, those already discriminated against by widening the area of systemic discrimination.

One of the sectors in which automated processes are increasingly used is that of criminal justice. Your book mentions several cases of real and serious injustices caused by a superficial and purposely discriminatory use of AI. Is there one in particular that strucks you more than the others? Could you tell us about it?

That is exactly the paradox I was speaking of earlier: the projects and projects of innovation and social support that should theoretically serve to benefit the more disadvantages, turn out, instead, to become tools for the surveillance and control of minorities. It is, in the final account, a dual exclusion. In the book I illustrated this point with the case of Omar, a 16-year-old boy who was the victim of predictive software used by law enforcement in the city of Amsterdam, which proposed to identify the adolescents most at risk of becoming criminals in the future solely on the basis of their personal date up to that time, and the histories of others with similar profiles. This is a method that has no scientific basis whatsoever, but is rather a typical case in which correlation is erroneously interpreted as causality. This was a revolutionary project that became pure dystopia in the way it was used: certain people were treated like criminals even if they had not yet committed a single crime.

Have the new technologies at least kept their promise to free women from the classical gender roles, or have they actually contributed to worsen their condition?

Societies evolve continuously, and the promises that are made during a certain period of history are difficult to maintain over the long term. When it comes to domestic technologies, for example, many innovations were developed for the purpose of lightening the load of housework without, however, considering the social impact that they would have. The new technologies created new, higher standards, with the result of increasing the amount of work women had to do in the home, since the new technology enabled them to do it in less time. The same thing happens now in the business environment: rather than allowing us to work less, the technologies prompt us to work even more than before, in many cases.

Certainly women are excluded, marginalized and penalized, as all the other social categories that have historically been discriminated against more or less structurally, and the more structural those discriminations are, the greater the risk that they will be incorporated, since the most recent versions of AI – based on statistics – are trained on historical data.

All technological revolutions, from those inherent to the sexual sphere to those regarding domestic life, despite the promises, have benefited certain already privileged categories of individuals, excluding, effectively, those already discriminated against by widening the area of systemic discrimination.

Why weren’t the first bicycles designed for women? What were the social and cultural reasons for this exclusion?

The bicycle is a good example of how technology can be perceived and experienced in completely different ways depending on the social group to which each person belongs. If it was mainly black and poor people who were excluded from the automobile bridge of Long Island, in the case of the bicycle, it completely ignored women, older people and children, because it was designed with only one type of user in mind, namely young men. In the history of the evolution of the bicycle, it is also interesting to note how, to open the floodgates and make this technology accessible to everyone, it was necessary for special interest groups, in this case feminists, to insist on facilitating the process of democratization or at least to see the issue from a different point of view, which initially had not been taken into consideration. This had a profound social impact on the popularity of the vehicle which, following the protests and expressions of interest, was redesigned to become what it is today (and that we completely take for granted).

Feminist movements have become involved repeatedly and with different approaches in the relationship between technology and gender issues. In some cases, like that of cyberfeminism, women have appeared favorable and open to the new technologies that tend to overcome gender binarism and achieve a fluid identity. In other cases, however, like that of the eco-feminists, women have come out against certain technologies, claiming that the technological culture is a product of male domination. How would you describe the relationship, and what are relations like today between feminism and technology?

I wrote this book just to stimulate a reflection on this subject. The question I ask at the outset is: «What are the feminist and social movements in general doing today with regard to these issues?» My impression is that we have completely stopped caring about them. These days, I think very few people understand the importance of the contribution of feminist movements to the study of technologies and their social impact. Although in the past there were different positions, some even contrasting with one another, with respect to the relationship between technology and gender issues, there was in any case a great deal of activity among the various feminist groups. Today, however, at least in Italy, I observe that the political and social movements often have little or no competence on these issues and considerable difficulty in conceptualizing them. I find the situation very troubling considering that just now we are beginning to have to deal with technologies that would require greater awareness and informed reflection, especially with regard to those marginalized groups who are the first victims of these innovations.

As you explain very well in different passages of the book, these days people, but particularly the media, speak about technological development, and especially AI, as if it were an independent, neutral and inevitable entity, thus contributing to absolve the human race of any responsibility. Why is this happening and what is wrong with this approach?

This happens for a lot of reasons. It depends, above all, on where the message is coming from. Mostly, it is coming from the business world, where there are significant economic interests at play, starting with OpenAI and with Elon Musk. In recent years they have been engaged in a process of mass psychological terrorism with respect to the impacts and existential risks that generative AI would have on society. They did this to try and convince us that the only people who can control these risks are the same ones who in many ways are causing the damage. If so many people believe this story, it is because we don’t educate them sufficiently to understand that it is a matter of choices. As I try to explain in the book, the idea of the “flash of genius” is erroneous and misleading: no one wakes up one morning and invents something that never existed before. Behind every innovation there are a great many people, years and years of work, billions of dollars of investment in one rather than another technology, and people in charge who decide which projects to move ahead on and which to quash.

What can we do to ensure that the technological revolution doesn’t bring a new revolution of involution and social exclusion?

We definitely need a strong collective conscience. From the standpoint of research, I think it is important to invest heavily in the less tangible but extremely real and imminent impacts that the new technologies have on our lives, and in understanding how to make artificial intelligence work for us in respect of social values and fundamental rights. In this, I have to say that Italy is not doing enough. Beyond the obligatory and natural application of what the European Union is doing (the AI Act, ed. note), Italy is not taking a strong position. Rather, the government wants to assign the role of guarantor and of vigilance on these instruments to a heavily politicized government agency (the Agency for Digital Italy – AGID, ed. note). I consider this to be a very questionable choice that goes in the opposite direction of the doubts and criticisms expressed recently by various associations and experts in the sector.

Alessandro Mancini

Has a Publishing and Writing degree from Sapienza University in Rome; he is a freelance journalist, content creator and social media manager. From 2018 to 2020 he was editorial director of the online magazine Artwave.it, which he founded in 2016, specialised in contemporary art and culture. His writing is mainly focussed on contemporary art, work, social rights and inequality.

![The Topologies of Zelda Triforce (Patrick LeMieux, Stephanie Boluk, 2018) [image from itchio]](https://www.the-bunker.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/The-Topologies-of-Zelda-Triforce-Patrick-LeMieux-Stephanie-Boluk-2018-image-from-itchio-thegem-product-justified-square-double-page-l.jpg)