Technology Triggers Anxiety—But Only in the West

by Camilla Fatticcioni

In the West, we live in the Black Mirror phase of technology—we fear it, we expect it to betray us, to invade us, to steal our jobs. In China, on the other hand, it’s the Star Trek phase: technology is a tool for progress, improvement, something that can make life easier.

The first time I arrived in Shanghai, in 2016, I was amazed at how cash had become practically useless. Pulling out a banknote felt awkward, outdated, almost folkloric. Everything was paid via QR code: the taxi, the steaming hot baozi bought on the street—even the beggar on the corner had a QR code to ask for alms. When I returned to Italy, I would talk about how convenient it was not to need a wallet when leaving the house. That was the precise moment I had the clear sensation that China was light-years ahead of Europe in terms of technology. But it wasn’t just about tools, devices, or infrastructure. There was something deeper: a different way of seeing technology as a resource.

Looking back at the articles I’ve written for this column, I’ve realized I often draw parallels with Black Mirror. What’s happening in China seems to precede the episodes of the famous British dystopian series—perhaps also because we, in the “old continent,” continue to view technology with a certain suspicion.

Not long ago, while listening to a podcast, I came across a quote from Kaiser Kuo, former communications director at Baidu and a clear voice bridging East and West. He said something like this: “In the West, we live in the Black Mirror phase of technology—we fear it, we expect it to betray us, to invade us, to steal our jobs. In China, instead, we are in the Star Trek phase: technology is a tool for progress, for improvement, something that can make life easier.”

In Europe—and perhaps even more so in the United States—our technological imagination is filtered through an anxious lens. Dystopian series, cyberpunk narratives, op-eds about the dangers of AI: everything seems to scream that we’re rushing headlong into an abyss. There’s a constant feeling that every advancement—an algorithm, a new app, a machine that listens to us—is a threat to our privacy, our freedom, or simply our humanity.

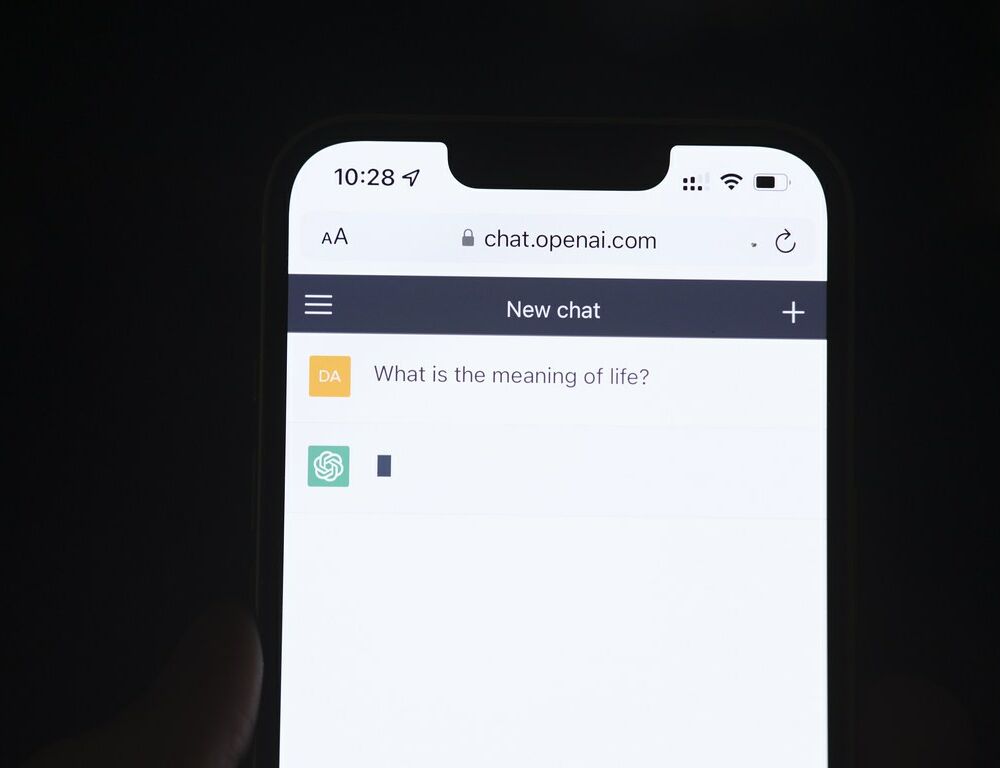

This isn’t a completely unfounded paranoia. We’ve seen the side effects of digital surveillance, platform capitalism, and information bubbles. But it’s also true that the dominant narrative in the West is profoundly pessimistic: it’s as if every innovation must be analyzed, weighed, and sometimes rejected, as though there’s always a trap behind it. We use new technologies, but not without a subtle distrust. We like to confide in ChatGPT, yet criticize AI-generated images and videos.

In China, technology is not perceived as a threat, but as a real opportunity.

This attitude stems from our history and myths: the same ones in which Prometheus is punished for stealing fire from the gods, or Frankenstein creates a monster. Every step forward seems to inevitably lead to something negative—we’ve internalized suspicion as a form of protection.

In China, the dynamic is different. Technology is not perceived as a threat, but as a real opportunity. It’s part of everyday life. AI suggests your grocery shopping on Taobao, books a doctor’s appointment in less than three clicks, and digital payments prevent any kind of tax evasion. It’s fully integrated into daily life and is welcomed with an almost disarming trust.

I remember a conversation with a Chinese friend. I asked her if it didn’t bother her that the government could access so much of her personal data. She looked at me, surprised, as if my question was out of place. “If technology helps me live better, why should I be afraid of it?”

China didn’t go through the trauma of the Industrial Revolution like Europe did, nor the post-70s privacy reckoning like the U.S. did. The approach is more pragmatic: if something works, you use it. Period. If it improves efficiency, comfort, or productivity, it’s enthusiastically adopted. This doesn’t mean there’s no debate—China also has critical voices about smartphone addiction or the impact of apps on younger generations—but the general tone is different. Anxiety isn’t the dominant feeling; curiosity is.

The divergence between these two visions is not just geopolitical or technological, but cultural. In the West, we’re obsessed with the concept of the individual, with personal freedom, with control. In China, where the collective has always played a more central role, innovation is also judged by the benefits it brings to the community—urban efficiency, general well-being, quality of life. The result is a more fluid, less conflictual relationship with technology.

The Chinese approach isn’t necessarily better. There are gray areas, of course, and complex ethical issues—especially when it comes to privacy and government surveillance. But it’s interesting to observe how the Western imagination is often trapped within itself.

Black Mirror scares us, but the title of the series itself is inspired by the reflection we see of ourselves on the black screens of our smartphones.

Camilla Fatticcioni

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a master’s degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.

![The Topologies of Zelda Triforce (Patrick LeMieux, Stephanie Boluk, 2018) [image from itchio]](https://www.the-bunker.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/The-Topologies-of-Zelda-Triforce-Patrick-LeMieux-Stephanie-Boluk-2018-image-from-itchio-thegem-product-justified-square-double-page-l.jpg)