LA RIVOLUZIONE ALGORITMICA

Who Controls the Machine

by Francesco D'Isa

A critical and philosophical look at artificial intelligence and its influence on society, culture and art. La Rivoluzione Algoritmica aims to explore the role of AI as a tool or co-creator, questioning its limits and potential in the transformation of cognitive and expressive processes.

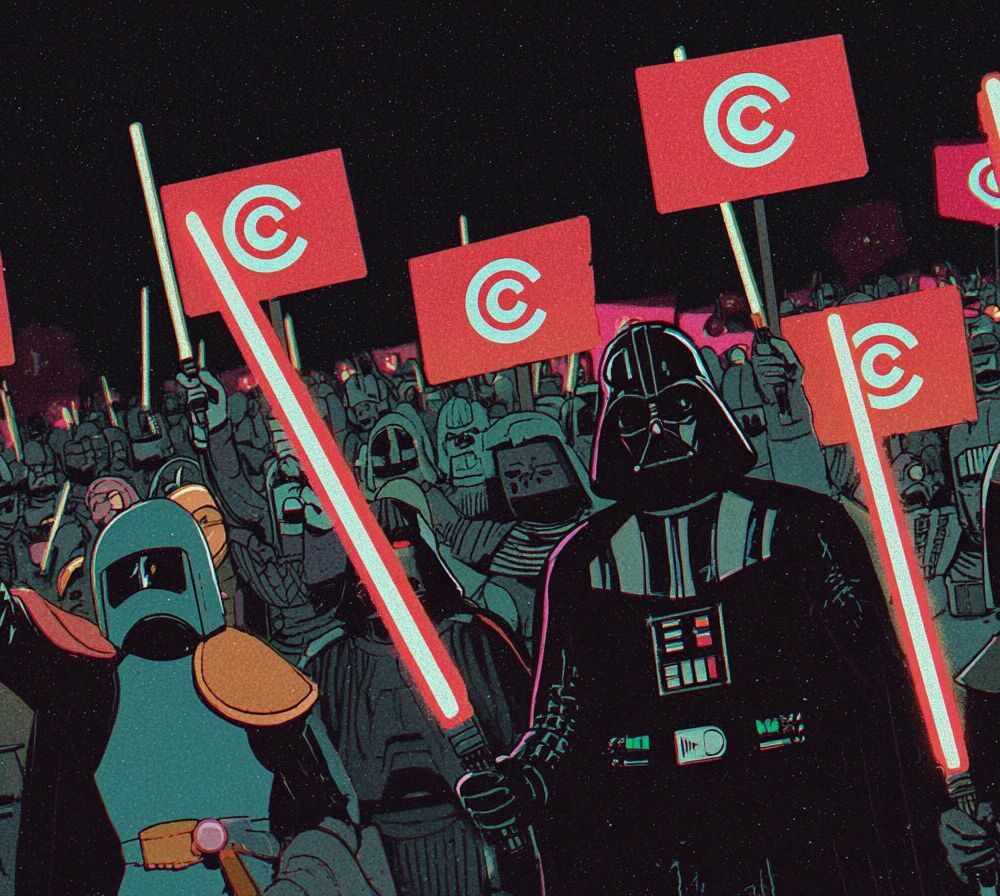

Every time a project born from generative AI gains some degree of visibility, polarisation is inevitable: on one side, those who glimpse the democratisation of knowledge; on the other, those who decry yet another act of capitalist expropriation. There’s no need to cite a specific example, because this has become the default frame through which the public sphere receives any AI-mediated production.

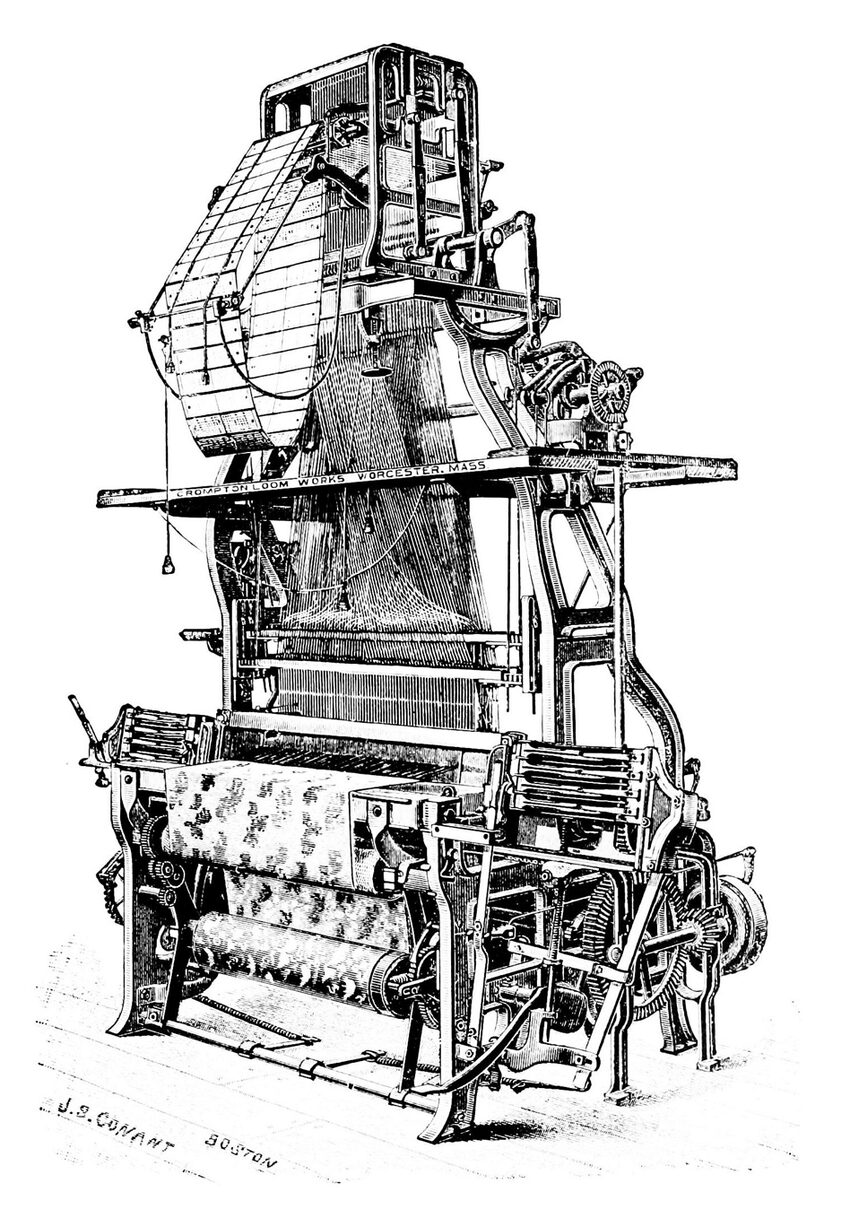

This is nothing new; two centuries ago, the Luddite weavers of Nottingham smashed looms not out of hatred for progress, but to demand that machines not become instruments of wage dumping. The same dynamic—recently recalled by John Cassidy in The New Yorker—resurfaces today with different players but identical fears. The issue, once again, is not the machine itself, but the political and economic orchestration behind its use and, above all, its profits. Stirring the barricades is a familiar dilemma: whether to boycott the tool and its users, or to learn it and put it to use.

The technologies that Lipsey, Carlaw, and Bekar refer to as general purpose technologies—those devices or infrastructures that, once introduced, spread horizontally across all sectors—have one relentless peculiarity: they make the cost of staying out prohibitive. The history of electricity illustrates this almost didactically. When, at the end of the nineteenth century, Edison’s system tied bulbs, meters, and generators to a proprietary architecture, no city could afford to remain in darkness waiting for an alternative; as the networks expanded, access to electricity became a precondition for economic survival. And it was this necessity—not some moral imperative—that drove municipalities to negotiate tariffs or establish public utilities, as Thomas P. Hughes recounts in Networks of Power.

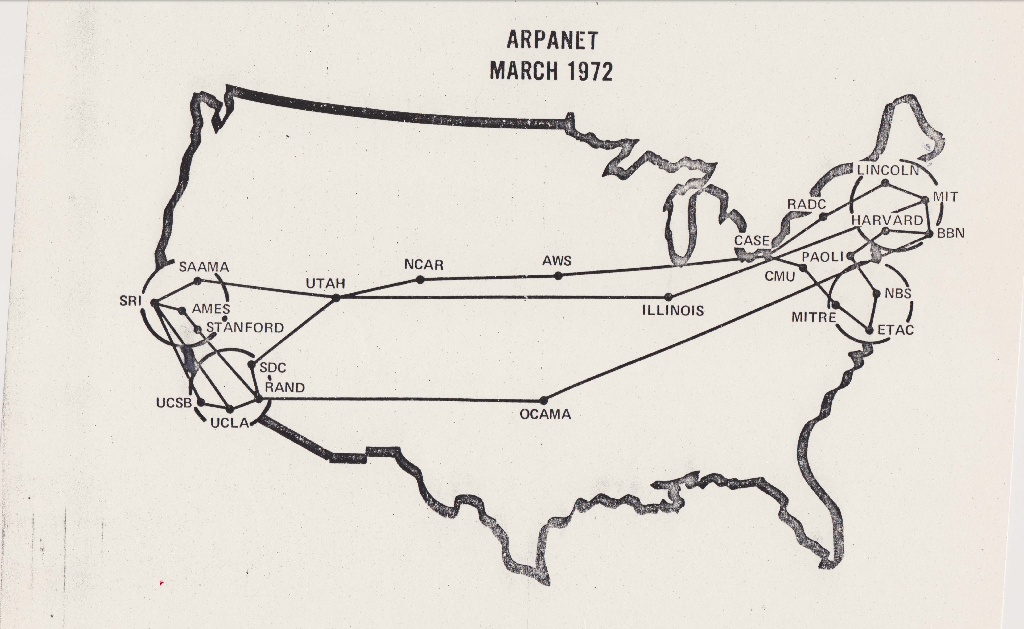

The same pattern recurred with computing: from government mainframes to the home computers described by Paul Ceruzzi, anyone seeking to remain competitive in research, design, or accounting could not ignore this new way of processing information; the price of abstaining increased with every software programme that became a de facto standard. Then came the Internet, and Benkler showed how network effects compelled individuals and businesses to connect, even knowing that the physical backbone was controlled by a handful of operators. The web had already become the global agora, and to forgo it was to self-marginalise.

The generative algorithm follows the same trajectory: its remarkable potential is likely to make it more of an infrastructural good than an optional tool – and in many cases, it already is. We can debate at length about the opacity of datasets or the monopolistic, proprietary systems, but meanwhile, universities, law firms, businesses, newspapers, and individual users are integrating its functionalities into their everyday workflows. Those who imagine boycotting AI because it was “born wrong” will soon find themselves in the position of a service worker refusing to use the internet.

In times that now seem distant, Gramsci reminded us that technology is never a neutral domain separate from culture. In Notebook 12, he writes that “there is no human activity from which one can exclude intellectual intervention; one cannot separate homo faber from homo sapiens”: if intellectual reflection is involved in every productive act, then technical literacy becomes a condition for any effective political action. In the pages of L’Ordine Nuovo, Gramsci wrote: “Industrial innovations […] allow the worker greater autonomy, place him in a superior industrial position […] The working class gathers around the machines, creates its representative institutions as a function of labour, as a function of the autonomy it has achieved, of its newly acquired consciousness of self-government” (14 February 1920). In other words, the machine becomes a factor of emancipation only when workers collectively gain control over it. In the same newspaper, a few months earlier, he insisted: “By imposing workers’ control over industry, the proletariat […] will prevent industry and the banks from exploiting the peasants and subjecting them like slaves to the safes” (3 January 1920). Technology, then, becomes a terrain of struggle: by mastering it, organised labour removes productive power from rent extraction and redirects it toward social ends. It is therefore not the machine itself that determines subordination, but the system that sets its tempo and captures its profits. From this emerges the figure of the organic intellectual: not a detached cleric, but a technical-organiser capable of uniting operational expertise with a collective project. In this light, artificial intelligence is not a gadget to be idolised or rejected, but the very ground on which a new subjectivity can test its capacity to govern productive forces and transform them toward emancipation. The urgent task is to understand and master the tool.

That is likely what AI pioneer Geoffrey Hinton meant in a recent interview when, asked what economic policies were needed to ensure AI worked for everyone, he responded with a single word: “Socialism.”

The debate on generative AI, by contrast, seems trapped in a cultural déjà-vu that Kirsten Drotner, in her studies on the history of mass media, calls media panic: an emotional cycle in which every new medium is accused of corrupting the youth, destroying employment, or undermining truth. As early as the 1990s, Drotner showed that panic follows a recurring choreography: the identification of a “vulnerable group”, a proliferation of alarmist headlines, calls for drastic measures, and finally, the medium’s assimilation into daily life. The same script has repeated itself from the 19th-century popular novel to comic books, from television to video games. Today, simply mentioning “deepfakes” or the label “AI-slop” can collapse the entire conversation into fears of an imminent cognitive catastrophe.

Yet, as Goode and Ben-Yehuda also observed, panic functions more as a ritual of symbolic stabilisation than a real risk analysis: it serves to sweep power relations off the table, shifting attention from the ownership of platforms to the morality of users. In the crosshairs end up image generators that are “too easy”, songs composed “without talent”, articles “written by a robot” – but rarely the patent chains, monopolies, or systemic exploitation that make such automation possible in the first place. The result is a short circuit: the more technology is demonised, the less we discuss governance and redistribution, leaving structural issues untouched.

Recognising media panic does not mean minimising the problems, but stripping panic of its paralysing role and returning to politics – not collective psychosis – the task of deciding who should govern artificial intelligence, and how.

In The Eye of the Master, Matteo Pasquinelli proposes approaching artificial intelligence through the lens of a labour theory of automation: behind the algorithm that appears to function autonomously lies a chain of human labour – annotators labelling billions of images for a few cents, moderators filtering toxic content, technicians monitoring data centres around the clock, communities freely providing their speech data to train voice models. Without these actions, the machine does not work.

Even computational power is not an abstract matter: the GPUs that process parameters (like much of our technology) depend on mines and power plants; they shift workloads to countries where energy is cheaper and environmental regulation is weaker, thereby reshaping industrial geographies and geopolitical alliances.

For Pasquinelli, the primary critical task is to bring the workforce that constitutes AI’s hidden core back into focus; if automation is a process that abstracts labour, the only way to re-anchor it in reality is to re-materialise it in all its phases.

From this diagnosis, I believe the most effective strategy does not lie in boycotting, but in reclaiming. This means giving names, wages, and rights to those who train and maintain the models; organising forms of unionisation among data annotators; demanding contracts that recognise the collective authorship of datasets and, by extension, the openness of the resulting outputs. It also means initiating independent audits of model weights and training logs, in order to break the proprietary opacity that transforms a public resource of accumulated knowledge – books, forums, sound archives – into private commodity.

And more: it means advocating for less extractive energy infrastructures, ideally funded through public GPU consortia, so that computing power may be treated as an essential service, on par with water or public transport. These and other initiatives should ensure that the productive force embedded in AI ceases to be a rent-generating tool for the few and instead becomes a shared resource.

If the goal is to challenge Big Tech’s absolute ownership of the medium, then the entry point is the opening of the code. Fortunately, there are already tangible cases along this path: on the textual front, the DeepSeek-LLM model – released in both 7 and 67 billion parameter versions – has been made available with weights included, ready for retraining; Mistral followed suit with its 7B series under an Apache 2.0 licence, which permits full freedom of study, modification, and even commercial use. In the world of text-to-image models, Stable Diffusion has already shown that publishing every line of code can foster thousands of independent forks, and a similar (albeit partial) approach can be seen with Flux, a 12-billion-parameter model developed by Black Forest Lab.

Yet open-source alone may not be enough: to prevent the same corporations from extracting value from the commons, we may need legal enclosures such as Dmytri Kleiner’s copyfarleft, which permits use within cooperative communities and obliges private profiteers to feed improvements back into the public domain. Then there remains the issue of hardware: without shared computational resources, access remains theoretical. That is why, as previously mentioned, public GPU consortia are being discussed – true “computational aqueducts” powered by renewables, where schools, libraries, and mutualist start-ups could train models without relying on Azure vouchers. Combining open code, protective licences, and collective infrastructures transforms openness from a symbolic gesture into a material power of co-management: it is the only way for artificial intelligence to shift from being a source of rent for the few to becoming a genuinely shared resource.

Over the past centuries, every general-purpose technology has demanded a reckoning: to accept the challenge and turn it into a site of struggle, or to retreat into a moralism which, in the name of purity, ends up freezing existing power relations. From the steam engine to electricity, from electronic computing to the internet, history shows that those who remain outside the circuit of innovation simply bear its consequences. Artificial intelligence is no exception. If left to the owners of data centres, it will become the most powerful infrastructure for cognitive value extraction ever created; but if we study it deeply, open it up, sustain it through public infrastructure and protect it with licences that reward cooperation, it can become a lever for redistributing time, income, and cognitive expansion.

To attack those who currently make use of proprietary models as if they were traitors to some ethical purity is a sterile and punitive stance. History teaches us that truly useful technologies do not retreat in the face of moral proclamations; they are absorbed—often problematically, yes, but almost inevitably—into both productive and symbolic circuits. It happened with electric power, with the personal computer, with social networks. And no one would dream of launching crusades against users.

This is why the most sensible battle is not to issue excommunications, but to pry open cracks in the black box. Does this goal sound utopian? Certainly; but it is even more utopian to imagine that, by boycotting AI, it will somehow vanish from the world. It is far better to understand it, manipulate it, overdetermine it from within—turning its presence into a space for collective struggle and experimentation.

Francesco D’Isa

Francesco D’Isa, a trained philosopher and digital artist, has exhibited internationally in galleries and contemporary art centres. After his debut with the graphic novel I. (Nottetempo, 2011), he published essays and novels for Hoepli, effequ, Tunué and Newton Compton. His latest novel is La Stanza di Therese (Tunué, 2017), while his philosophical essay L’assurda evidenza (2022) was published by Edizioni Tlon. His latest publications are the graphic novel Sunyata for Eris edizioni (2023) and the essay La rivoluzione algoritmica delle immagini for Sossella editore (2024). Editorial director of the cultural magazine L’Indiscreto, he writes and draws for various magazines, both Italian and foreign. He teaches Philosophy at the Lorenzo de’ Medici Institute (Florence) and Illustration and Contemporary Plastic Techniques at LABA (Brescia).

![YESTERDAY WAS MY BIRTHDAY SO I ASKED FOR LEGS TO RUN AWAY (Yannis Mohand Briki, 2024) [3]](https://www.the-bunker.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/YESTERDAY-WAS-MY-BIRTHDAY-SO-I-ASKED-FOR-LEGS-TO-RUN-AWAY-Yannis-Mohand-Briki-2024-3-thegem-product-justified-square-double-page-l.jpg)